A few years ago we spent a magical morning visiting the Etruscan tombs in Tarquinia in the north of Lazio (the Roma Region). There are dozens and dozens of tombs that you enter down a flight of stone steps. There were not that many tourists that day so you were able to see the colourful frescos without a big crowd. What a variety of images – people eating and drinking, exotic animals, hunting, fishing, dancing, making music, jugglers, flogging, and many more from Etruscan society over 2600 years ago. You really got a palpable sense of the past in the present. Also a strange encounter with death, with the other side, since these sacred places were never meant to be opened for our human eyes. What you could not see in these tombs were the objects – the statues, jewellery and other fine or useful goods that were left beside the dead person to accompany and protect them on their journey.

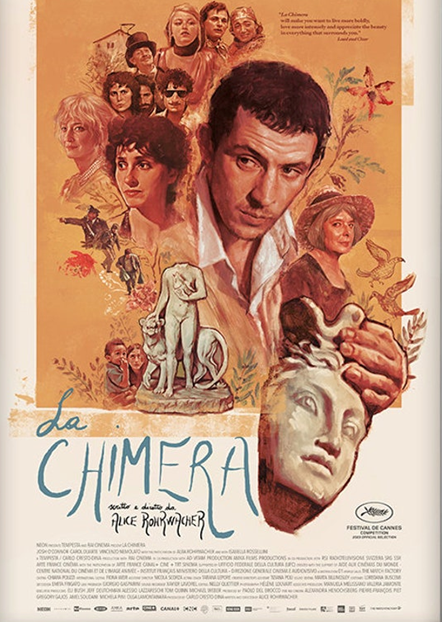

This film was made in the Tarquinia area of Italy, near the 200 or so tombs you can see at the archaeological site. The absolute centre of the film is this disconcerting space – the Etruscan tomb. There are two groups of people who spent time and energy searching for these hidden tombs with their beautiful frescos, fine objects and their evidence about Etruscan life. On one side, you have the archaeologists, usually supported by the state. On the other side are the tomb raiders – the tombaroli. Another two key groups of actors are the official musuem curators and the art collectors – some of whom are willing to buy illegitimately acquired artefacts. Artur, the central character of this film, has been trained in archaeology but he has become part of a band of tombaroli who live in a small deprived town near the tombs,

We are not given the full background of Artur and why he has chosen this life which certainly has not brought him any wealth. There is a suggestion of a tragic romance with one of the local women and he is befriended by her mother. He is in demand by the local thieves because he has some sixth-sight method of finding the tombs by using what looks like a twig water diviner method. The doomed romance, his relative poverty, and mishaps with the law means he hardly smiles throughout the story. It is almost as he himself is content to be obsessed with the boundaries between life and death. Unlike the various groups of tomb robbers, he is scarcely interested in the money generated by the loot. He is genuinely interested in the aesthetic beauty of the objects.

The director, Alice Rohrwacher, has a keen eye for class, oppression and exploitation . Her previous movie Happy as Lazzaro, which is also worth seeing, examined the lives of a super-exploited rural community. Here we see how the better organised tomb raiders with links to organised crime rip off the more haphazard group around Artur. Then we see how the people who really controlled the whole operation were the top criminals with links to the parallel art market. A key scene in the film is when the gang have gone to a boat on a Swiss Lake where some sort of shadowy auction is taking place. Artur takes it on himself to sabotage the auction. Ian Parker, a fellow ACR contributor to this site, made an acute comment on Facebook about this:

“and then Artur is reluctant to let it dissolve into mere market value (simply for ‘exchange’); he values what he finds for its beauty, and that kind of value (‘use’, we might say) is as much a chimera as the woman he lost and still pines for (the red thread of the film).“

Chimera means an impossible dream or an illusion. Both in tragic love with Beniamina and in his archaeological pursuit, Artur is chasing something he is not able to finally grasp. There is poetry, anguish and deep sadness in this character, played very believably by Josh O’Connor (yes, he played the youthful Prince Charles in The Crown). Rohrwacher takes you to places you have not thought or felt about in a way the average commercial conventional drama or blockbuster rarely does. By the end of the movie you really start to care about Artur. Since a lot is only intimated obliquely by the director, the viewer is able to use their imagination to speculate about his life. In most films every dot and comma of the character is laid out and shouted at you. Towards the end of this film the pace meanders a bit and you keep thinking it is finishing now, but stay with it as there is a very poignant ending.

Since the 1990s the tombaroli are much less in evidence as thankfully the Italian state has taken on board more seriously the need to protect its enormous cultural and artistic heritage.

The director combines a sort of gritty social realism, as she recreates a particular fragment of early 1970s Italian society, with Felliniesque fantasy sequences to communicate the feelings and thoughts of her main character. Some critics have rightly commented that Rohrwacher makes films like poetry with subtle, allusive images and script. Certainly there are a number of layers that you can unpack with this film and probably means it would repay a second viewing. The best films often do.

Art (54) Book Review (127) Books (114) Capitalism (67) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (45) EcoSocialism (60) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (62) Film (48) Film Review (68) France (72) Gaza (62) Imperialism (100) Israel (129) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (56) Labour Party (113) Long Read (42) Marxism (49) Marxist Theory (47) Palestine (181) pandemic (78) Protest (153) Russia (343) Solidarity (149) Statement (50) Trade Unionism (144) Ukraine (351) United States of America (136) War (370)