“Milk is something we’re all familiar with.” The opening gambit of the Welcome Collection’s excellent current exhibition, Milk. Everything else displayed then attempts to defamiliarise us with this historically and ideologically charged liquid and, in doing so, illuminates its political and cultural meanings.

The exhibit is well curated not to overwhelm attendees while offering plenty on which to reflect later. It is split into two parts. The first includes the sections “the story of milk”, “the milk problem”, “good health”, and the second, “scientific motherhood”, and “the cost of milk”. They examine, respectively, cows’ milk and human milk.

To do this, there are an array of artefacts. Included are Victorian cream jugs; posters, leaflets, and books from various eras; photographs, recordings and short films; sculptures (such as a scaled-up udder in the entrance) and tit coins, satirical art pieces created by Jess Dobkin and Lisa Kiss mocking the commercialisation of milk. The overall effect is to create not a jumble of conflicting aesthetics but to reveal an unfolding official story and the counterhegemonic attempts to disrupt and change that account.

Modern Cows

The exhibit traces the regular consumption of fresh cows’ milk as short ago as the early 20th century (mainly in urban centres) rather than endorsing a notion of a direct and ancient continuity of the practice. Indeed, such narratives were used to obscure and thereby promote the role of milk in European states, replete with all their colonial projects, as what increasingly became an essential food for growing populations of workers.

This history is one of evolving (often tragically mistaken, but sometimes progressive) notions of nutrition and hygiene, driven by the intertwined but conflicting needs of nationalisms, corporations and human wellbeing. It is a process that created cultures of consumption and class (particularly in ideas of aspiration), which filter down to us today albeit in still contested forms.

Furthermore, it is a history marked by a problem of cleanliness and disease, notably tuberculosis, a challenge addressed by the creation of public health sciences. In milk, we can see the culmination of previous centuries’ shaping of the state as something that manages (or attempts to), cares for, and controls its populations, underscored by capital’s requirements.

These requirements extend to the ability of states to wage war against each other, a topic that is the focus of many of the exhibits. We see how women were brought in large numbers into dairy production and farming during wartime, and how the propaganda of such periods established lasting notions of the meaning and connotations of milk.

Social Reproduction

Not separable from the account of dairy milk, is the story of human infant feeding. And again, it is one intimately bound with the institutions of power and their regulative ideology. The most relevant plaque brings attention to the disciplining and standardisation of motherhood that was entailed in treating breastfeeding as an activity needing professional oversight, rather than occurring through familial instruction and human agency:

The idea that women need scientific advice to successfully care for and feed their infants took hold in Europe and North America in the late 19th century. It stemmed from the rise of paediatrics and was reinforced through adverts for newly available infant formulas.

While a scientific approach brought benefits to maternal and child health, it also reshaped motherhood. Feeding schedules applied discipline to infant nourishment and milk became measured and monitored. Health visitors and doctors used babies’ weights to track their development, as adverts claimed baby formula was a ‘perfect substitute’ for breast milk. Paediatric research was developed around white women’s bodies, leading to bosses in maternal health care.

This new approach produced a standardised image of motherhood that persists. Perceived ‘failure’ to meet these standards can create feelings of shame, particularly around infant feeding. Today, more inclusive practices are being developed that understand how infant feeding is affected by factors including family, race, workplace, income, and healthcare systems.

If I were to raise quibbles with the exhibit, it would be about the sentiments expressed in that last paragraph. Both in how it articulates a naive credulity concerning the present and its overall advances and in the limits of the list of possible areas of inclusiveness (omitting reference to queerness or disability and collapsing class into the vaguer and depoliticised notion of income).

But there is plenty to praise, not least the handling of imposed racialised understandings of motherhood. Social reproduction, the usually unpaid or underpaid sustenance of workers with many associated prejudices, is wrested from its typical invisibility by many curation choices.

Indeed, reference is made elsewhere to the association between whiteness and milk. An association that gifts a powerful symbolic tool to the arsenal of the far right to this day. In our time of creeping fascism, alongside the emergence of less defined but still reactionary and racially charged nostalgia cults for “trad wives” and male domination, this is a timely observation.

Power

Elsewhere, I have explored the idea of normalisation and naturalisation through a marxist lens. In that earlier piece, I wrote:

Marx… realised that the way we organise ourselves inevitably shapes our sensuous realities and how we experience daily life and that this shapes our ideas about the world and what is possible.

Although it does not adopt an (explicitly) marxist frame, Milk is bringing to light the shaping of our ideas by the sensuous world of class society. And as with Marx, understanding power (its usually concealed formation and maintenance) is crucial to understanding and overcoming the injustices embedded in this process.

The example of Nestle, briefly mentioned in the exhibit, brings such dynamics of power (and exploitation) to the forefront. I could not do full justice to the subject here, but Nestle’s promotion of formula in various underdeveloped countries has long been linked to dangerous nutritional problems and is the subject of the documentary Tigers, as well as a recent report from Unicef.

Further Reading

In attending the exhibition, I benefited from the company of my sister. She is a breastfeeding counsellor and a Doula who now helps new mothers, and is far better informed than I will ever be on the subject. She graciously fact-checked my review (although I retain responsibility for errors) and recommended two books on the subject by Gabrielle Palmer:

Why the Politics of Breastfeeding Matters. (A good, short primer on the subject.)

The Politics of Breastfeeding. (A longer and more in-depth examination.)

Art (54) Book Review (126) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (45) EcoSocialism (58) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (61) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (72) Gaza (62) Imperialism (100) Israel (129) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (56) Labour Party (114) Long Read (42) Marxism (50) Marxist Theory (48) Palestine (177) pandemic (78) Protest (154) Russia (341) Solidarity (146) Statement (49) Trade Unionism (142) Ukraine (349) United States of America (134) War (368)

Latest Articles

- The cost of lives lost and yachts bought – the Covid PPE contracts scandal

When the current Labour government took power, one of the targets on their radar was the recovery of some of the funds spent on defective PPE by the previous Tory government, writes Joseph Healy.

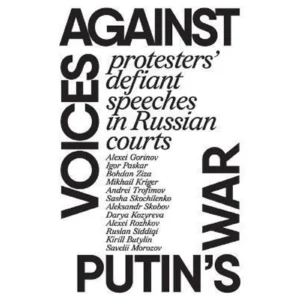

When the current Labour government took power, one of the targets on their radar was the recovery of some of the funds spent on defective PPE by the previous Tory government, writes Joseph Healy. - Voices against Putin’s war

Voices against Putin’s war. This book contains protesters’ defiant speeches in Russian courts, published October 2025 by Resistance Books,.

Voices against Putin’s war. This book contains protesters’ defiant speeches in Russian courts, published October 2025 by Resistance Books,. - Lecornu mark 2 – a government at war with working people

Statement by the French Anticapitalists (NPA) following the failure of the no confidence motion and the formation of a new pro-Macron government led by Lecornu.

Statement by the French Anticapitalists (NPA) following the failure of the no confidence motion and the formation of a new pro-Macron government led by Lecornu. - Starmer defends racist Israeli football fans

Dave Kellaway reports on Starmer’s attempt to present Maccabi football fan ban as antisemitic

Dave Kellaway reports on Starmer’s attempt to present Maccabi football fan ban as antisemitic - A Festival of Obsequiousness

Trump at the Knesset and Sharm el-Sheikh proved a theatrical ordeal, writes Gilbert Achcar.

Trump at the Knesset and Sharm el-Sheikh proved a theatrical ordeal, writes Gilbert Achcar.