Many of us must have been surprised and even shocked to see Teresa May, as Prime Minister giving her disastrous ‘coughing’ /P45 speech at the 2017 Tory party conference, wearing a bracelet with Frida Kahlo images. Who knows how ignorant May was of the artist’s political commitment.

However, it does reflect how the political nature of Frida’s art has been often submerged under her emergence as a commoditized icon particularly from the end of the 20th Century. Her style, her personal life, physical ailments, and sexual relationships have taken centre stage. It is wonderful that she is admired as an independent, bisexual feminist. Exhibitions like the one at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 2018 focussing on her collection of traditional Mexican dresses and other possessions are fine. If the Frida Kahlo Barbie doll leads some young girl to find out about her life that is a good thing too. However, as art historian, Janice Helland notes:

Kahlo’s works have been exhaustively psychoanalyzed and thereby whitewashed of their bloody, brutal, political content

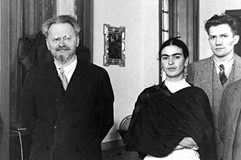

Kahlo joined the Communist Party in the 1920s and remained involved in anti-imperialist politics all her life. Along with Diego Rivera, her muralist painter husband, she provided a refuge for Leon Trotsky, despite the murderous opposition of her comrades in the Mexican Communist Party. She had a brief affair with Trotsky but political differences later saw an estrangement and a return to pro-Stalinist positions.

I have seen several Kahlo exhibitions but they tend to include all the classic pictures, mostly self-portraits which often paint her pain and impairment as no other artist has ever done. The picture we have selected is therefore one that is less well known but more directly political. It was painted when Rivera and she were in the USA of the New Deal era where her partner was commissioned to do some large murals.

Like some medieval altar diptych (two panels) Self-Portrait on the Borderline Between Mexico and the United States illustrates a clear dichotomy between the two countries. As with nearly all her pictures, Frida is present in the middle dividing the two visions. The Mexican side is represented by colourful images of nature, history, and cultural heritage. You see Aztec statues and the key Sun and Moon symbols of its culture as well as the terraced buildings of its cities. The rubble and the skull lying on its side suggest how the conquistadors from Spain destroyed this civilisation. On the United States side, there is a landscape of dull grey factories and pollution. You can pick out Ford on the chimney stacks. The steel pipes have a semi-human shape perhaps indicating factory workers. The Stars and Stripes are shrouded in smog.

The flag in Kahlo’s left hand and the direction of her gaze shows she identifies with Mexico. Along with other artists she grew up in the wake of Zapata’s mass 1910 nationalist insurrection. Intellectuals and artists wanted to forge a new Mexican consciousness freed of the European colonial imprint and imbued with the spirit and values of pre-Columbian civilisations like the Aztecs and Mayas.

The electrical wires and generator shows the power fuelling US industry but ominously they are also attached to the plants and crops of Mexico on the left – expressing the exploitative, neo-colonial nature of the United States relationship with its southern neighbours. It is not an equal relationship, one side has crucial power. Today the US still maintains that relationship in different forms. Its capital exploits cheap labour in the assembly plants along the border. The US economy hugely benefits from the cheap undocumented labour which it also strictly controls and represses. The painting could almost be read as having a certain ecological consciousness about what US capitalism does to the world of nature.

In some respects, the picture works as a mini mural with its simple, clear images and agitprop style. At the same time, there is a personal aspect. Kahlo’s expression reflects her state of mind at the time. She did not particularly enjoy her time in the States and was happy to return home. It is worth comparing this picture to another painted a year later.

These pictures still speak to us today about the reality of neo-colonial relations and the ecological crisis. They help make sense of our existence:

Pain, pleasure and death are no more than a process for existence. The revolutionary struggle in this process is a doorway open to intelligence.

Frida Kahlo 1907-1954