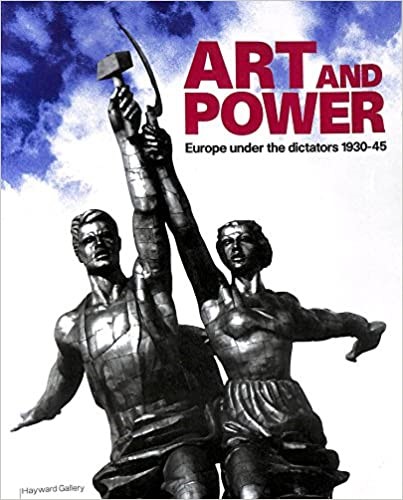

Art and Power

The image above is of the cover for the guidebook of the 1995 Art and Power exhibition at the Hayward Gallery[i] in London. It features the famous giant, stainless-steel Worker and Kolkhoz Woman statue by Russian sculptor Vera Mukhiya, produced for the 1937 international exhibition in Paris. The statue topped the Soviet pavilion, which stood directly opposite the pavilion of Nazi Germany (see below), which featured a giant eagle—one of the many occasions that Nazi Germany and fascist Italy made an implicit reference to the Roman empire[ii].

1937 Paris. Nazi and Russian pavilions confronted each other

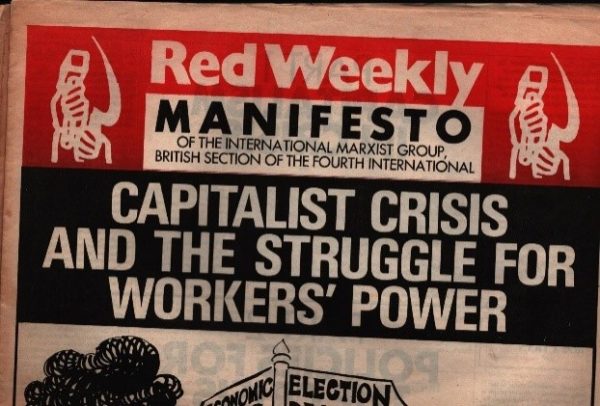

A stylised version of the statue’s hands holding the hammer and sickle was adopted as the symbol of the French Ligue Communiste (later LCR) in the early 1970s and was then used by many other sections of the Fourth International in the 1970s and ‘80s, including the International Marxist Group (IMG) in Britain.

The exhibition, subtitled Europe Under the Dictators 1930-45, collected a large array of artworks from fascist Italy, Nazi Germany and Communist Russia, as well as from both sides in the 1936-9 Spanish revolution and civil war[iii].

The crab in action. Not all readers immediately understood it.

In his introduction to the book, Eric Hobsbawm argues that art under dictators had three functions. First, giant statues and architecture demonstrated the power of the incumbent regime. Second, public spaces, like the Nuremberg stadium where the annual Nazi rallies were held, provided the setting for public ritual and drama. And third, state-directed art was meant to propagandise for the existing power structure. The result of course was to fatally undermine the critical and creative edge of artistic production. Hobsbawm rejects the notion that art must be apolitical, which he attributes to American liberal thought (‘art for art’s sake’). But art produced to laud the existing regime was inherently conservative and usually produced dire and kitsch results.

Hitler had been to art school, regarded himself as an artist, and rejected, as did his regime, the experimental German art of the pre-Nazi Weimer Republic as ‘degenerate’, especially as much of it, together with German cultural production in general, was produced by intellectuals of Jewish origin. Max Ernst and Georg Grosz, forerunners of Dada and Surrealism, were particularly reviled—realism was essential for the Nazi version of art as propaganda. Like their Italian cousins, the Nazis made implicit and explicit reference to the sculpture and architecture of Rome. Idealised Graeco-Roman-style nude statues, especially male nudes, were confusingly meant to evoke the Teutonic tradition which had resulted in one of Rome’s biggest defeats in the Battle of the Teutoburg Forest in 9AD—at the hands of Germanic tribes. The preference for this sort of nude artwork is part of the scant evidence falsely used by some writers to allege that the Nazi leadership (or even Hitler himself) were mainly gay[iv].

Hitler’s own artistic tastes were decidedly conservative, and his personal collection of several hundred paintings concentrate on Germanic landscapes and ‘Aryan’ nudes. Like the other dictators, Hitler had numerous paintings of himself produced.

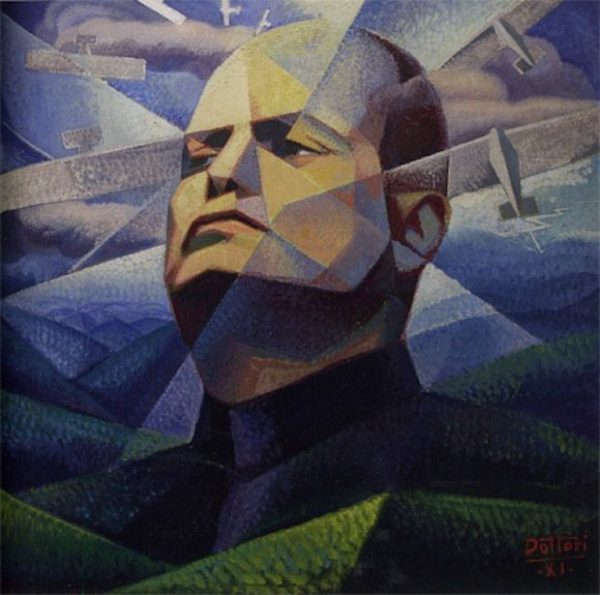

Unlike Hitler, Mussolini showed little interest in art, and for a time innovative modernist artists like the Futurists produced pro-fascist art, Mussolini by Futurist artist Gerardo Dottori

without being reigned in. But after the fascist regime was formally declared in 1923, art was pressurised to become more conservative. Some of the Italian painting of the 1930s is less obviously propagandistic than that of Nazi Germany but still stuck in the rut of conventional realism[v].

Mussolini by Futurist artist Gerardo Dottori

Lasting monuments to fascist architecture in Italy include Milan’s famous railway station, a giant building that consciously tries to reproduce the style of the Roman empire, and the mosaics outside the Rome Olympic stadium (video here).

Growing Stalinism in the 1920s put an end to experimental Soviet art. As is well known, Russia’s artists became strictly controlled and forced into so-called Socialist Racism, featuring endless portraits of Stalin with adoring children and peasants, and terribly interesting pictures of machine tractor stations.

As in Germany and Italy, Soviet architecture was designed to show the power and strength of the regime. Some experimental modernist architecture was built in the early years of the Soviet regime[vi], but by the late 1920s mainly gave way to huge and drear office blocks, department stores and workers’ flats. The buildings, towering above the surrounding areas, were meant to demonstrate the power and solidity of the regime—and overawe the masses much like the Catholic cathedrals of European feudalism. A few of these buildings managed to maintain experimental modernist lines and were often colourfully refurbished after the collapse of the Soviet Union[vii].

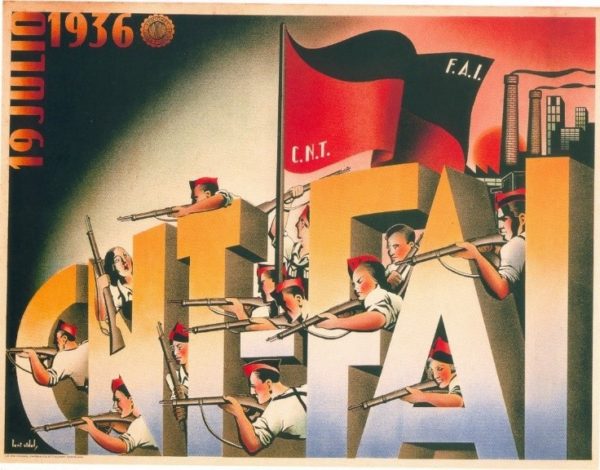

One of the many dire Socialist Realist portraits of Stalin

Among the liveliest and most interesting artefacts in the exhibition were the many colourful posters and other artworks from the Spanish civil war. All the anti-fascist forces in Spain, from the Stalinists to the POUM[viii] and the anarchists, used advanced modernist graphic design motifs, often strongly influenced by contemporary art deco styles. The art of Spanish Catholic fascism, by contrast, is dark and morbid, full of depictions of the crucifixion and nuns with their eyes upturned to holly light descending from the clouds.

1937 anarchist poster from Catalonia

At the time of the 1937 Paris exhibition, the Spanish republic had not yet fallen, and the Spanish pavilion foregrounded Picasso’s legendary depiction of the bombing of the Basque city of Guernica, by the German Condor Legion, a part of the Luftwaffe, deployed, like hundreds of German soldiers to aid the fascist forces.

Also reproduced in the exhibition were the famous anti-Nazi montages by Communist artist John Heartfield. He fled Germany when the Nazis came to power, living in Czechoslovakia and then Britain, where he was interned as an ‘enemy alien’. He eventually went to East Germany, where his critical independence made him suspect to the Stalinist regime.

Left Guernica, right John Heartfield montage

Thanks to Rob Marsden and Red Mole Rising for ‘crab’ hammer and sickle images.

[i] Hayward Galleries Publishing 1995.

[ii] A glimpse of the use of the eagle, and the public drama of Nazi ritual, can be grasped in the scenes from Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will linked here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Hu-CK47NM8E

[iii] Best explained in Pierre Broué and Emile Temime, The Revolution and the Civil War in Spain, Haymarket 2008.

[iv] This preposterous idea was most recently popularised in the 1995 book The Pink Swastika by Scott Lively and Kevin Abrams, which circulated among extreme right-wing American groups. The claim that only ‘feminine’ gays were persecuted in Germany.

[v] See Jonathan Jones’ demolition of a 1912 Florence exhibition that tried to rescue 1930s Italian art from fascism https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2012/sep/24/art-fascist-italy-paintings-florence

[vi] See https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/world-history/soviet-architecture-a7608371.html

[vii]https://www.featureshoot.com/2014/03/frank-herfort/

[viii] United Marxist Workers Party, see Broué op cit.