A 1944 Pastoral: Land Girls Pruning at East Malling by Evelyn Dunbar (1906-1960)

I first saw this picture a few weeks ago on a visit to Manchester Art Gallery. I took a photo on my mobile phone. It was a picture of record, a document but much more than that. There was an old master look to it with the composition of the figures and landscape with its non-natural lines. The combination of the central picture and the vignettes around the border of the pruning tools and the Cezanne-like fruit was also a bit different. You got the illustrations you might find in a training manual alongside the main picture. The deeper link between them of course is that all the women in the picture had to learn these new tasks, using tools they may not have used before. A lot is being communicated here.

Maybe it attracted me because it is something I do – prune fruit trees so that the air can pass and the rest of the tree is reinvigorated. The picture reminded me of some oil paintings from the past which combined tools or instruments around a central picture. The colours are end of autumn/winter browns and yellows. It conveys the sense of working together purposely to get a job done. Only half glimpses of Individual faces are shown and the women are all wrapped up warm with headscarves against the chill. The artist is conveying the cooperative, the collective effort. Female strength is emphasised with a woman carrying a big ladder dominating the foreground. This is not just a back garden operation. Your eye is taken to the central horizon of the picture, down the long alley of the orchard into the distance. No this is part of a much bigger national mobilisation to keep British people fed during the Second World War.

These are land girls working at Malling in Kent during the Second World War in 1944. As men were called up for military service, there was a huge labour shortage on the land which was a lot less mechanised than today. Women responded to the campaign. They usually had to leave home and stay at hostels at the farms. Evelyn Dunbar was an official war artist, there were a few women war artists but she was the only one kept on a salary throughout the war. Since she was working for the government all the pictures are the property of the state. Most are available to view online and there are well worth a look. Lots of different farming tasks are shown and there are more intimate pictures of the women in their hostels where you get a sense of female solidarity and new friendships. The picture also made me think of my own mother. My mother worked as an Air Raid Protection (ARP) warden in the war and was based in Bristol, a city that was bombed fairly heavily. She often talked favourably of that time and the opportunity to undertake work that was traditionally the domain of the male workforce. However, as the war drew to a close most women were pulled back into the home as they married returning soldiers. This suited the state with the need to find returning servicemen work and many women were encouraged to leave jobs they had covered with distinction during the war years. Nevertheless, these experiences did change many lives.

For me, the picture also paints a positive picture of working with nature. A couple of hours working in the garden or an allotment gives you a sense of physical satisfaction, working with living nature and getting a job done. Your body interacts in a different way – you get scratched, dirty and smell the leaves and wood close up. It is never quite the same as two hours in front of a screen, however happy you may be with your research or finished article.

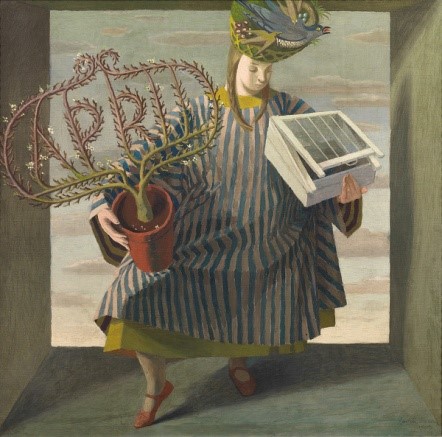

In fact, Dunbar’s passion for working the land also related to her Christian Scientist faith which has a central belief that God gave people the earth in a contract to manage in the best possible way. All her life she was a keen gardener and her second marriage was to a horticultural specialist. She did beautiful illustrations for gardening magazines of different garden plants. Again with a nod to tradition in art from the middle ages, she drew beautiful symbolic invocations of each month. Here is April, opening up the cold frames at last and holding a pot of flowers bursting into bud.

She was also a skilled muralist. Her first husband and she illustrated the Aesops fables on the walls of what was then Brockley school (today Prendergast). Although she still kept painting after the war until an early death she only was able to organise one solo exhibition and did not really get the recognition she deserved – like many other women painters. That is until this picture was taken to the BBC’s Antiques Roadshow in 2012.

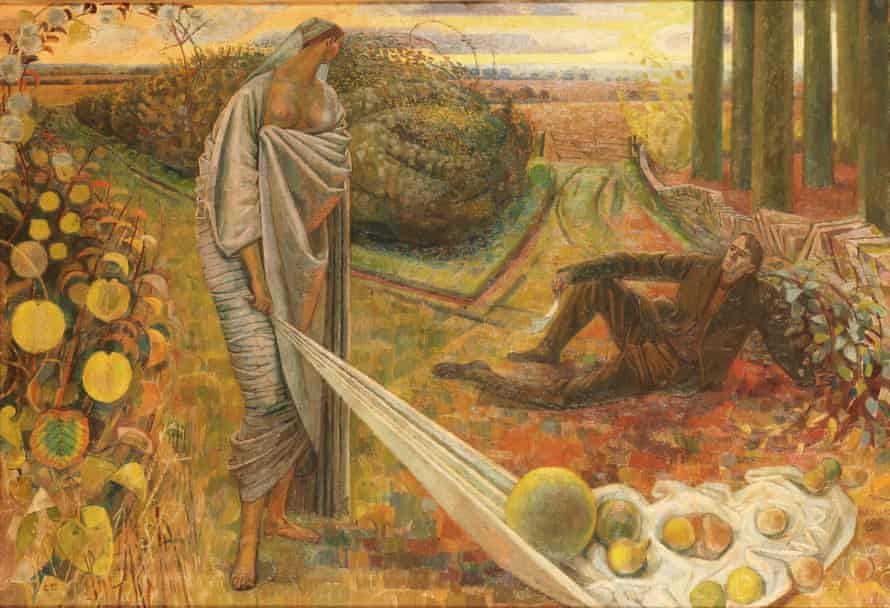

The poet was modelled by her husband and the muse of autumn by his sister. This picture prompts critics to highlight the influence of the pre-Raphaelite painters of the second half of the 19th century on her. Like her, they were often inspired by religious, mystical subjects. Often they painted formalised, detailed bright natural landscapes. This sumptuous picture shows Dunbar had a far greater range than her wartime work suggests. The colours are all autumnal warm reds, yellows, and browns. For her, it was landscape and nature that inspired artists.

The Antiques Show specialist was completely bowled over by this work and estimated a price upwards of forty thousand pounds. Luckily a niece of Dunbar was watching and decided it might be worth investigating the attic where her aunt had left some stuff. She uncovered over 500 paintings, drawings, and preparatory sketches – doubling the amount of Dunbar’s known work. An exhibition was set up and today even her student efforts go for tens of thousands of pounds. Stuart Jeffries in a Guardian article gives a lot more detail on this story.

Here to finish up are another two beautiful works. The first captures a moment during the war when people are queuing because they heard some fish was available. The second is a great picture of a young RAF woman concentrating on preparing vital weather forecasts for the air force.

Section officer Austen, Women’s Auxiliary Air Force meteorologist

L S Lowry became very popular with his matchstick people urban scenes in the post-war period but in my opinion pictures like the queue at the fish shop are more evocative, more human. Lowry became very famous but Dunbar remained catalogued as quite a minor artist.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women

The main picture has a certain look of Brueghel about it. Lovely.