During the McCarthyite witch hunts in 1950s America it was believed a homosexual underground existed as part of a “communist conspiracy”. It was sometimes called the Homintern (after the Comintern, the Stalinist Communist International). The fearful authorities went so far as to depict this “threat” to security as a contagious social disease. It was illegal to be gay and despite rabid persecution by the FBI and other state agencies, some brave souls formed a “homophile” association called the Mattachine Society in 1950.

Harry Hay, a longtime member of the Communist Party, was among the first to point out that homosexuals were a “cultural minority” and not just individuals. He and the Mattachine society even begun to call for public protests for gay rights, prefiguring later gay pride marches. Hay was expelled from the CP in 1951 as a “security risk”. The only other group on the left to come close to supporting gay rights was the Young Socialists, influenced by the Independent Socialist League, which in 1952 published an article in the Young Socialist Review.

The new decade of the sixties blew apart the repressive political climate and stifling, conventions of the 1950s, with massive civil unrest throughout America. The Black Civil Rights Movement was on the march against racism, and later the more militant Black Panther Party fought for Malcom X’s uncompromising stance of political and social revolution. Black communities rose against poverty and social injustice with “race” riots in many US towns and cities, notably the Watts uprising of 1965 that lasted 5 days, finally suppressed by the presence of 14,000 national guards!

There were huge demonstrations against the Vietnam war from 1967 onwards. Students rebelled and demanded greater democracy and freedom in education. The “counter-culture” refused to conform to the dictates of bourgeois social norms. The growth of the Women’s Liberation Movement began a journey towards self-determination and freedom from the straitjacket of oppression and second class citizenship.

Despite all of this radical and revolutionary activity there still were those in the gay rights movement urging a more cautious approach: “We homosexuals plead with our people to please help maintain peaceful and quiet conduct on the streets of the (Greenwich) village” This plea from the Mattachine Society in 1969, now more conservative in outlook, was posted in a window of the Stonewall Inn three months after the riots.

The MS had become a liberal lobby group trying to influence and educate the great and good towards a greater tolerance of homosexuality. Spooked by the spontaneous uprising of the oppressed they sought to prove that gay people could be assimilated into bourgeois society. The new Gay Liberation Movement rejected this reformist direction. Only full, unconditional acceptance would be allowed against the patronising ‘tolerance’ of the liberal establishment.

Gay people, living under conditions of illegality, had become easy prey for police entrapment, blackmailers, queer-bashers, criminal gangs, homophobic employers and landlords and were refused entry to straight bars if their behaviour or appearance was ‘odd’.

The Stonewall Inn gay bar on Christopher Street, Greenwich Village, was the centre of liberal/radical/artistic/bohemian life in New York. The Genovese crime family (Mafia) controlled the bar. Almost all of the gay bars were controlled by organised crime and money was extorted through overpriced alcohol, watered down beer and blackmailing the richer gay clientele. The bar was also paying off the police to allow this to happen, in weekly envelopes of cash.

The bar had no liquor licence, no running water, overflowing toilets, no fire exits, and drug dealing was rife. Customers were inspected through a ‘speakeasy’ peep-hole by a bouncer and, to avoid undercover police entrapment, only those that were known or ‘looked gay’ were allowed entry. People rarely signed their real names in the ‘guest list’ book which was required by law to gain entry. The age of the patrons ranged from late teens to early thirties, and there was an even racial mix between white, Black and Hispanic people. It was the only gay bar in New York where dancing was allowed. The patrons included homeless young men who would try to get in for free drinks from customers, drag queens, transgender people, effeminate young men, butch lesbians, and rent boys, but the customers were overwhelmingly cisgender male – some of the most oppressed sections of the working class.

Police raids against gay venues were routine and frequent. The Stonewall was raided at least once a month and patrons were arrested, handcuffed and herded into police wagons. Often the management knew about the raids beforehand and they were staged early enough for the patrons to restock the bar from hidden supplies and carry on serving once the police had gone. The mafia still wanted its cut of the profits! As Martin Duberman described in Stonewall (1993), paraphrased by Wikipedia, this was the modus operandi during the raids:

…the lights were turned on, and customers were lined up and their identification cards checked. Those without identification or dressed in full drag were arrested; others were allowed to leave. Some of the men, including those in drag, used their draft cards as identification.

Women were required to wear three pieces of feminine clothing, and would be arrested if found not wearing them. Employees and management of the bars were also typically arrested. The period immediately before June 28, 1969, was marked by frequent raids of local bars—including a raid at the Stonewall Inn on the Tuesday before the riots—and the closing of the Checkerboard, the Tele-Star, and two other clubs in Greenwich Village.

Things came to a head when, so it was rumoured, the police were no longer able to receive kickbacks from blackmail and payoffs, including the theft of negotiable bonds from threatened gay Wall Street employees. It was more than likely that the Public Morals or the Food and Drugs Administration had decided to close the Stonewall Inn permanently on alleged “health and safety” grounds, as had happened with other bars in the neighbourhood.

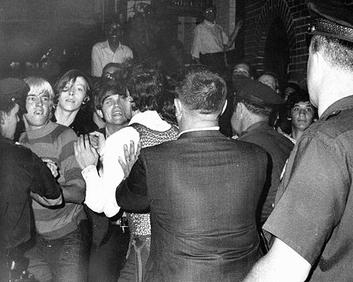

People defied the police. They refused to show ID cards or be hustled into the bathroom so that police could verify their sexual identity. Men in drag were arrested. Those not arrested congregated outside the bar and were joined by others in increasing numbers from the neighbourhood. Some were rescued from the patrol wagons, and when a lesbian resisted arrest the police beat her and knocked others to the ground.

The increasingly angry crowd pelted police with coins and bottles, followed by bricks and stones from a nearby building site. Barricading inside the Stonewall Inn, the police were forced to call for assistance. From that point, as crowds swelled over several successive nights, the whole thing escalated into a full blown uprising. It took three days and nights before the Tactical Patrol Force, trained to deal with Vietnam war protests, could finally subdue the rioters.

The rioting was not organised or orchestrated by any group. It was a spontaneous uprising by people who had been beaten down to the lowest level of human existence by repressive anti-gay laws, corrupt police and unscrupulous officials in cahoots with criminal organisations. After years of unchecked oppression they had reached the end of the tether and vented their fury on the oppressors. However despite the initial spontaneity of the uprising, leaflets appeared, one reading “Get the Mafia and Cops out of Gay Bars”.

Others called for gays to own their own establishments, for a boycott of the Stonewall and other Mafia-owned bars, and for public pressure on the Mayor’s office to investigate the “intolerable situation”. Within days of the rioting, groups sprung up to demand equality, and the Gay Liberation Front was born. Within a year or two, GLF organisations had spread to many towns and cities throughout the USA, making radical, revolutionary demands in line with black and women’s liberation movements.

The establishment of the Gay Liberation Front in Britain was a much more subdued affair. It was founded at the London School of Economics and Political Science in 1970 by two Maoists, Aubrey Walter and Bob Mellors. Clearly they were unaffected by Mao Zedong’s “Cultural Revolution” in China killing many thousands or the fact that homosexuality was regarded in China as ‘disgraceful’ and ‘undesirable.’

Walter and Mellors had visited America and were mightily impressed by the gay movement there. The home grown GLF imported the radical politics of its sister organisations in the USA and the revolutionary demands of the movement are embodied in the Gay Liberation Manifesto of 1971. Almost in a parallel way to the GLF in America, groups sprouted up in many towns and cities in Britain, and practically every University had a GaySoc.

The GLF experimented with consciousness-raising “think-ins”, alternative lifestyles to what was expected in bourgeois “straight” society. Many campaigns were enhanced through street theatre and direct action, challenging anti-gay moral crusades, repressive legislation, media censorship and social intolerance. Always with a clear anti-capitalist objective in mind.

Feminist, academic, and lesbian Elizabeth Wilson later looked back on the achievements of the Gay Liberation Front:

The ‘Manifesto Group’ was one of many launched in the ferment of activity that was the Gay Liberation Front in 1970-71.

Today it seems incredible that so many young adults had the time and energy to devote themselves full time to political struggle (although incidentally many of us also had paid jobs – the workplace just wasn’t as demanding as it is today).

GLF is best understood as a fabulous political firework display. Demonstrations, sit-ins, drag events, consciousness raising groups, street theatre, night graffiti raids, workshops, rallies, dances and ‘think-ins’ were all included in the stellar spectacular that was GLF.

The Manifesto Group came from the ideological, intellectual side of the movement and debated the question: What was it about society that led to the oppression of lesbians and gay men? The Manifesto’s answer was what would now be termed a ‘functionalist’ one: that capitalism ‘needed’ gay oppression – to shore up the nuclear family (a big bugbear for radicals at the time) and to police citizens into conformity.

The Manifesto reads today as a fairly one-dimensional attempt to account for gender and sexual victimisation. However, it asked an important and still relevant question about the sources of prejudice and hatred. The group met in my basement living room throughout a rather hot summer.

The atmosphere was sometimes tense and febrile, but however black and white the answers we developed appear today, it seemed crucial at the time to understand better the nature of the society we lived and live in. If it seems both raw and over-simplified now, it did actually (along with the work of feminists) spark a way of thinking about human relations in society that has led to significant change.

Like all pioneers, we sometimes got it wrong, but we believed in what we were doing. We believed in our power to change society. And that is surely a good thing.

Elizabeth Wilson has captured the political zeitgeist of the 1970s that affected the GLF. Scarcely a day would go by without some form of struggle, whether it be strikes, demonstrations, sit ins or pickets. Not just in the labour movement but across the board including School Students’ strikes, anti Vietnam War demonstrations, Troops out of Ireland, anti-apartheid movement, Anti-Nazi League, the burgeoning Women’s Liberation and Black power movements, the start of the Environmental-Green Movement, continuing counter-cultural influences, the student movement sparking educational reforms and prompting the labour movement to engage with political issues beyond the workplace, the squatters’ movement for housing and alternative lifestyles and so on.

Despite all that there was little connection between the GLF and the labour movement — hostility and distrust existed on both sides. Despite some Marxist and socialist individuals, the GLFers hitched their wagon mostly to the Women’s Liberation Movement and to a lesser extent to the Black Liberation movement. Although macho posturing and an aversion to gay people was an impediment, Huey Newton, cofounder of the Black Panther Party, made a strong statement urging solidarity with the Gay and Women’s Liberation Movement. Still others took the view that Black gay men were being traitors to their race for not producing Black children!)

The lack of connectedness to the labour movement considerably diminished the GLF’s understanding of the need for solidarity work with working-class organisations and why that was important. Patriarchy and male privilege had been identified as the main enemies rather than capitalism and many gay radicals felt that ridding the world of male power and male chauvinism and throwing in our lot with the Women’s Liberation Movement was sufficient to bring about gay equality and liberation.

Over time, this chasm meant that Liberation politics became associated with the demands of radical liberalism often informed by postmodern academic theory rather than socialist goals. The class divides within the struggle festered, and aims for incorporation into bourgeois society (legal rights, especially marriage) prioritised over problems that particularly impacted LGBTQIA+ workers and unemployed (unequal medical access, homelessness, workplace discrimination). Identity and difference became the watchwords, rather than unity and revolution. As the labour movement receded in power and influence in the defeats of the 80s and winter years of the 90s, generational gaps emerged too as valuable skills were lost.

Transgender liberation often maintained a radical core. The foundations of the modern movements were laid down by theorists and activists like Sandy Stone in her seminal The Empire Strikes Back: A Posttranssexual Manifesto and the revolutionary socialist Leslie Feinberg’s 1992 pamphlet Transgender Liberation: A Movement Whose Time Has Come. These built on the 1970s legacy of those like Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, whose post-Stonewall organisation Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries (STAR) anticipate contemporary transgender and gender non-conforming resistance.

Various groups from Rikki Wilkins’s GenderPAC to Queer Nation emerged in the 90s to represent the liberatory politics of a more comprehensive understanding of gender and sexual minorities, cementing the reclamation of the word queer in political consciousness. But much of this politics remained on the one hand in conflict with the apathy or hostility of a weakened labour movement and socialist organisations, and on the other with the often trans-hostile or trans-apathetic liberal orgs (most notably, in the US context of the time, the Human Rights Campaign that showed quite tepid support for trans struggles.)

The trans struggle has now stalled. In the US, Southern Republican controlled states have fought the culture war while out of power by imitating the spirit of Section 28 from late-80s Britain, creating infamous “Don’t Say Gay” legislation around classrooms. Transgender peoples’ access to facilities, civil protections and healthcare, commencing with trans youth but inevitably impacting transgender adults too, has been rolled back. In the UK, too, a vicious moral panic chiefly focussed on trans women have seen basic social goods withdrawn and hate crime escalate against trans people specifically, but also all LGBTQIA+ individuals.

Today it remains a big task to stop queer people from being separated from our class and to raise awareness that as part of the working-class struggle for emancipation we can share in the potential to overthrow capitalism. I say our class because the overwhelming majority of queer people are in fact working class and bear the same burden of exploitation and oppression as others.

Art (55) Book Review (127) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (46) EcoSocialism (60) Elections (85) Europe (46) Fascism (67) Film (49) Film Review (69) France (72) Gaza (63) Imperialism (101) Israel (131) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (57) Labour Party (116) Long Read (42) Marxism (49) Marxist Theory (47) Palestine (186) pandemic (78) Protest (154) Russia (346) Solidarity (153) Statement (50) Trade Unionism (144) Ukraine (352) United States of America (140) War (371)