Although streaming has suffered setbacks, it remains the preeminent mode of mass entertainment today. And whatever its long run financial viability, with increasing competition damaging its selling-point to consumers by increasing the number of necessary subscriptions, streaming nonetheless continues to churn out a bewildering array of content.

Thanks to streaming as well as the impact of the internet, there has been a general nichification of media. It is now rarer to meet anyone who has seen everything you have seen. From the sureties of the age of Blockbusters and long running soap operas, today what you watch is often as highly curated and personal as the branded construction of your social media presence.

Horror, already niche, has consequently flourished. Stranger Things was one of the most-watched shows in 2022, with strong horror elements. The voyeuristic and controversial true crime Dahmer was high on the list too. Meanwhile, the reboot for I Know What You Did Last Summer gained attention on Amazon Prime. This winter, I have enjoyed a lot of horror, all exemplary of how streaming has shaped the genre for better and worse.

Full Of Woe

Tim Burton’s Wednesday is a case study for horror streaming, the kind of show that would likelier have been a film a few decades ago. As a franchise the Addams Family has always flourished. Both of Barry Sonnenfeld’s 90s movies were liked, and its successes go back to Charles Addams’s New Yorker cartoons of the late 30s. From its roots it has been a loving satire of the maudlin and monstrous, of the American gothic.

Of all the franchises’ characters, Wednesday is likely the most popular and certainly has the darkest sensibility of the titular family. She plays into the goth girl whose capacity for nihilism mocks adult condescension. She was the highlight of the Addams Family Values (1993) where Christina Ricci’s interpretation (Ricci reappears for Burton) defined her for modern audiences; her antics include staging a violent rebellion against the insufferable Camp Chippewa and its corny, revisionist thanksgiving.

As with the earlier imagining of the character, the action here takes place against the background of the genocide of indigenous Americans, albeit from a quite external perspective. Moreover, Wednesday continues to be set against institutional limitations, with a children’s summer camp now a teenager’s boarding school. Again, she rejects authority with relish. Again, there is a subverted romantic subplot. And again, the actor, now Jenna Ortega, proves the part’s match; delivering what has universally been heralded as an outstanding performance.

But another franchise haunts Burton’s Wednesday. From the magical boarding school to the motif of chosen ones; from the good vs. evil finale (however thinly veiled) and supernatural abilities to an emphasis on clubs and the pressures of coming of age; to the attempt to situate the Addams Family within a coherent mythos with highly defined parameters, this is Netflix’s answer to the increasingly toxic (thanks to its author’s transphobia) but still profitable Harry Potter franchise, controlled by a key rival—Universal.

I enjoyed the series. But I enjoyed it most when it recalled Sonnenfeld’s work, and least when it played into the Millennial generation’s cloying nostalgia for Rowling’s overrated Earthsea meets The Worst Witch knockoff. Not only do I find boarding school politics and dualistic morality plays inherently uninteresting, but the shift from a decisively English set of tropes to an American backdrop is clunky.

Either way, Wednesday is about nostalgia, aimed oddly (for such a surfacely youthful show) at my age bracket; it recalls narratives made popular in the 90s. It feels intensely of the 90s in its plot beats and sensibility. Whether this will work, and Netflix can make this franchise function as Star Wars and Marvel have for Disney, is unlikely. In the meanwhile, I hope season two has more of Ortega inventing dance routines and delivering droll quips to psychotherapists, and less dull exposition about types of monsters.

Curiouser and curiouser

Guillermo del Toro’s Cabinet of Curiosities is no less strange but more niche. It is an anthology in which each episode centres on a new monster, and has a different director. The man bringing this together, del Toro, is a master of conceiving monsters, and so the premise has a logic.There is a lot of experimentation and ambition involved, too, but that also means the series can miss as often as it hits.

Guillermo Navarro ‘Lot 36’ is a forgettable demonic revenge story, while Vincenzo Natali’s ‘Graveyard Rats’ is a silly, ham-fisted tragicomedy about grave robbing. Similarly, ‘Pickman’s Model’ by Keith Thomas and ‘Dreams in the Witch House’ by Catherine Hardwicke (both H. P. Lovecraft adaptations) have there moments, but fail to sustain an atmosphere of dread. All four episodes are awkward period pieces; intentionally or not, they are too hammy.

However, Panos Cosmatos’s ‘The Viewing’ was not forgettable, if still awkward. The wealthy Lionel Lassiter and his physician Dr. Zahra hosts a group of eccentrics (a musician, physicist, author, and a psychic) for an at home discussion. They talk, drink, take drugs and amidst the vaporwave, 80s aesthetics, things get eerie. Then the titular viewing commences and the ordeal takes a monstrous and violent turn. It is hard to know what to take away from it, but the set design and atmosphere are consummately rendered and the overall experience, unique.

David Prior’s ‘The Autopsy’ and the wonderfully subtle pastiche of American consumer culture, ‘The Outside’ by Ana Lily Amirpour, were strong successes. The former has the best creature concept, and I enjoyed its mix of world weary and idealistic characters in a rural, American setting. Whereas ‘The Outside’ is like what would happen if the Coen Brothers directed horror. It is surreal, at points whimsical, and delves into a small-town America critique of the beauty industry, of media confected anxieties and modern alienation more generally, which ends up as perceptive as it is disturbing.

Ultimately, were you to watch one episode from this show, it should be the final one. ‘The Murmuring’ by Jennifer Kent (adapted from one of del Toro’s own short stories) centres on a married couple, ornithologists, staying in a remote island house to study bird murmurations. They are grieving their lost daughter, Ava, and slowly (the pacing is superb) one of them, Nancy, encounters supernatural events.

The episode is stunning. Both performances are understated yet capture the deuteragonists’ heightened emotions. From the cinematography of the claustrophobic house to that of the birds, each scene is perfectly composed; from how nothing is told to the sustained ambiguity about events, the narration augments a sense of pathos and hope. As a standalone (if short) haunted house film, it would rate among the best; it certainly stands out in the context of the Netflix series.

Laments

While Wednesday has perhaps been praised excessively for reviving an old franchise, the new Hellraiser has met the opposite fate. Most fans of Clive Barker’s Hellraiser, based on his novella The Hellbound Heart, agree that the first one is a low budget horror masterpiece, the second a flawed but clever gem, and all the others, which did not involve Barker, cynical cash-ins getting progressively worse. I would argue that this was a turning point, but I seem to be in a minority.

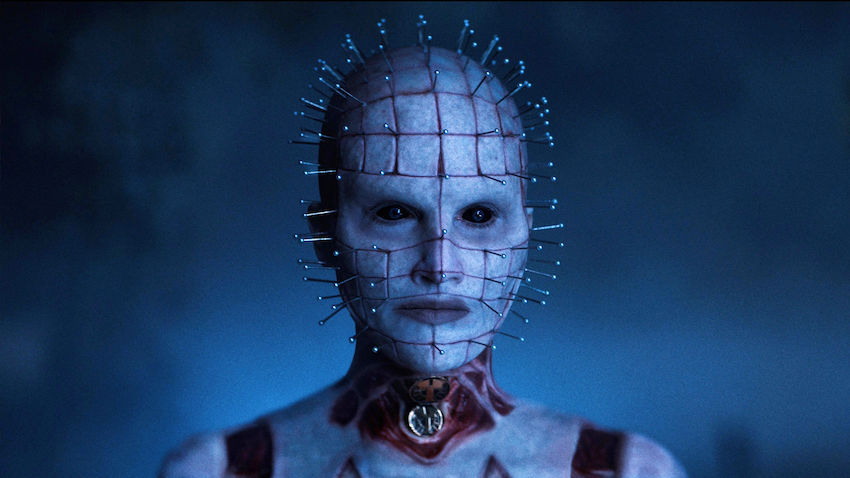

David Bruckner’s filmic effort, based on a screenplay by Ben Collins and Luke Piotrowski, and produced with Barker’s blessings, is a concerted attempt to return to the magic of 1986. It gained attention primarily for the casting of a trans woman, Jamie Clayton, in the role of Pinhead, the leader of the Cenobites who serve as the primary antagonists in most narratives that take place in this world of hedonistic Faustian pacts.

As with most trans representation, the choice garnered an immediate culture war backlash. But reactionary outrage about the queering of a book by an explicitly queer author like Clive Barker was more farcical than annoying; Barker’s work has always played with gender and sexuality, and anyone who seriously engages with the film, even many of its detractors, have conceded that Clayton owned the part—as even the beloved original performer in the role, Doug Bradley, acknowledged.

Reboots are tricky, but this one strikes a balance between updating reference points, while retaining Barker’s themes of transgression, hubris, excess, and transcendence. Tonally it is great; we are offered an amoral, occult universe haunted by beautiful grotesques, unifying demonic and angelic qualities. And even better, it is set against the trappings of our neoliberal dystopia, where conspicuous consumption resides side by side young precarious renters forced into ever more desperate grafting and self-degradation.

Finally, the soundtrack elevates everything. Ben Lovett’s wonderful new score pays homage to Christopher Young’s compositions from the 80s, but in keeping with the reimagining again updates it, adding grandiosity. It has all the weirdness of Young’s horror music, but picks up on the metaphysical ambitions and playfulness of Bruckner’s vision and adds notes of newer popular music. I hope that this film is soon reappraised.

Faustian Homes

For the British stop-motion animation anthology, The House, writer Enda Walsh brings together a huge directorial/writerly pool of talent (Emma de Swaef, Marc James Roels, Niki Lindroth von Bahr, Johannes Nyholm, Paloma Baeza) to tell three stories in what seem to be different realities, but within the same house. Each makes excellent use of the eerie appearance and movements of stop motion to construct worlds that blur the familiar with the horrifying.

‘And heard within, a lie is spun’ is a macabre fairytale, with the young Mabel drawn into relocating to the house that is part of the Machiavellian machinations of mysterious architect Mr. Van Schoonbeek. Dwelling there is difficult as it is constantly reconstructed around them. Moreover, the place begins to corrupt her family, playing on their anxieties about social status as people who have suffered a downward class trajectory. Meanwhile, the resemblance between the place and Mabel’s old doll house takes on greater and greater significance.

Anthropomorphic rats inhabit the world of ‘Then lost is truth that can’t be won’, which focuses on one such creature, renovating the place for resale. In a sequence that unfolds like a comedy of errors, he is plagued by a bug infestation, then by a couple who move in but refuse to purchase. However, as the story persists it becomes clearer that our hero is not as in command of reality as he initially seemed, and his relationship to the house is just one symptom of his troubled state.

The final episode, ‘Listen again and seek the sun’ is simultaneously the most despairing and hopeful. Its flooded apocalypse is populated by anthropomorphic cats. Rosa, the house’s landlord, attempts to develop the place while water rises and her few, non-paying tenants (Elias and Jen) aspire to leave. Everything changes when she meets her seeming antagonist, the throat-singing Cosmos. In an ensuing showdown, the notion of roots (also raised in the previous episodes) is challenged, as the end-of-the-world is imagined as a fresh beginning.

Today’s Horrors

Horror expresses the anxieties (and therefore hopes) of audiences. These horrors share a preoccupation with the past, and a sense that something vital has been lost. Relatedly, they are concerned, with different levels of explicitness, with ambivalence about the future. The House clearly articulates this dynamic at the level of myth, while Wednesday unconsciously channels such apprehensions. Like The House, both Hellraiser and the best of del Toro’s anthology is intrigued by redemption, in overcoming our epoch’s grief. However, only the final episodes of the two anthologies manages to wager on the possibility of such redemption, on something new.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War