You’ll have to move fast to catch Sylvia: A Musical Revolution at the Old Vic in London because it ends on 8 April. It is definitely worth trying though, not for detailed historical accuracy but for an energising, moving interpretation of key political developments through a contemporary lens.

Sisters

Ian was given theatre vouchers to be able to see this by his sisters and was able to scoop up some good seats, perhaps because Emmeline Pankhurst was being played by the understudy, Hannah Khemoh, who did it with gusto and an amazingly powerful voice. Sharon Rose played Sylvia Pankhurst with passion, and these two black women carried the show.

Terry went to a matinée on March 8, International Women’s Day, with four other socialist feminists generally familiar with the events being retold. Along with the rest of the packed audience, including a large party of school students, we thoroughly enjoyed ourselves. One of the party members commented that she generally disliked musicals and wasn’t keen on hip-hop but was completely won over.

One of the party commented that she generally disliked musicals and wasn’t keen on hip hop but was completely won over.

Terry was silently concerned about the fact that Beverley Knight, by far the best known of the cast members, with her hugely powerful voice and stage presence, was playing Emmeline. She feared this might mean that she, rather than Sylvia, would come over as the central figure—and gain more sympathy than she thinks her politics deserve. But the lesser-known Sharon Rose as Sylvia swept these worries away—in every area of performance, from acting to movement to singing.

Act One

Ian feels that the first half of ‘Sylvia: A Musical Revolution’ tends to reduce what the Pankhurst’s are up to in their family; we have the deaths of the father and the younger brother, and rivalry between the three sisters clamouring for their mother’s attention.

Even more problematic is the Corbyn-style handsome bearded white man, Keir Hardie, being petitioned by the women, promising and then failing, and then speaking out in Parliament—well, singing out, actually. It is made to seem very much as if Sylvia’s relationship with Keir was the driver of her link to left-wing politics. You blink and gulp and try to remind yourself that this isn’t really ‘Keir’, and the weird accent this guy on stage comes out with helps you distance yourself from what is going on.

Terry agrees that there are tensions between the political and the personal in the script and performances, but generally thinks these work. On the one hand, the political schisms between Sylvia on the one hand and her mother Emmeline and elder sister Christabel on the other hand have been chronicled many times, but the setting of this piece necessitated examining some of the more personal dynamics. Though the action all happens after his death, Richard Pankhurst’s role is portrayed as more significant than in other telling’s of the same story, and while she will definitely have to do more reading to see whether this is accurate, she thinks it works for this creation. And while elements of the Sylvia/Keir relationship are unique to Kate Prince’s script, the outline is accurate: they did have a long affair kept secret from his wife that ended only with his death, and she did paint his portrait.

Probably the sharpest differences between Terry and Ian’s readings of the musical are about the general theme of personal and political Ian refers to ‘the women singing about being the change that they want to see’ as anachronistic. This suggests both that such sentiments were not part of the suffragette’s motivation and that the production company is wrong to suggest they were.

Probably the sharpest differences between Terry and Ian’s readings of the musical are about the general theme of personal and political Ian refers to ‘the women singing about being the change that they want to see’ as anachronistic.

Terry believes that while the slogan the ‘personal is political’ was only articulated this way by second wave feminists, the underlying theme is one that many revolutionaries and particularly feminists have struggled with, particularly in periods of political turmoil. The writings of Alexandra Kollontai and Edward Carpenter are important illustrations of this, but the life stories of individual suffragettes also raise similar questions.

So she thinks that the confrontation between Christabel, portrayed as being in a lesbian relationship with Annie Kenney, and Sylvia over the contradictions of her relationship with Hardie is not farfetched. Ian suggests that Christabel, with her severe haircut, is being portrayed as outflanking Sylvia from the left. Terry thinks that this, balanced by the critique (albeit in passing) of Emmeline and Christabel’s support for war and eventually for the Tories, is intended to raise questions about the different strategies for achieving universal suffrage.

Terry does agree that the use of pacifists waving CND placards against engagement in the First World War does not quite work; she thinks it is an attempt by the production team to build links between peace movements across generations, but because the nuclear symbol is so literally central to that graphic, a misplaced one.

And she agrees that the potential contradictions of family are not teased out—in particular when it comes to the way the Churchills—mother, son, and wife—are portrayed. Very amusing but rather thin is the best that can be said.

On the other she thinks that other elements of the production deserve a mention from the impressive orchestra and the staging which was choreographed both athletically and in a way that subtly underlined relationships between characters in a way more reminiscent of a modern ballet than most musicals.

Act Two

The second half opens with some strong resonances with the struggle of women today against the current wave of misogynist violence, with a ‘Suffra-jitsu’ staging of the kind of self-defence the Suffragettes had to learn. At this point, the audiences got more lively, and that really helped. The young contingents were noisy in their enthusiasm, and the musical built to a climax as the women fought and won the day.

The horrors of the cat-and-mouse tactics used by the government to push the women on hunger strike—egged on by deeply sadistic prison guards—are dealt with through staging that is symbolic rather than triggering. This way, the horror comes from the calculated cruelty rather than an immediate shock.

There were a few hisses and boos when Emmeline Pankhurst said that she would be standing for the Tories, and there were cheers when Sylvia and Silvio got together, and approving sighs when Silvio later appeared on stage pushing a pram. This sounds awful, doesn’t it, but it was actually great fun, and it’s not clear whether it’ll be hip-hop or feminism that wins the day for the audience; perhaps it’ll be a dialectical combination of both, something they’ll take forward for themselves.

There were a few hisses and boos when Emmeline Pankhurst said that she would be standing for the Tories, and there were cheers when Sylvia and Silvio got together, and approving sighs when Silvio later appeared on stage pushing a pram.

We ended in 1928, when all women got the vote, and the applause of the audience was amazing to hear. There is always a kind of ‘fourth wall’ in the theatre, with the audience watching the three-sided stage as if they are not part of the action. This was a case where the fourth wall was broken through a little, maybe just enough to enable participation and a sense of what collective feminist struggle might feel like.

This was particularly the case on 8 March when there was a prolonged standing ovation for the whole cast, during which each of them took centre stage, mostly by performing extraordinary acrobatics.

We ended in 1928, when all women got the vote, and the applause of the audience was amazing to hear.

Act Three

There is no Act Three in this production. It is a play of two halves, so you’ll have to follow up on what Sylvia did and did next elsewhere. What we don’t get in the musical, and it’s difficult to know how that would be staged, is Lenin having Sylvia in mind as one of his targets in “Left-Wing” Communism: An Infantile Disorder. She refuses to orient the newly-founded Communist Party as an officially-recognised section of the Third International toward the Labour Party and is viewed as ultra-left.

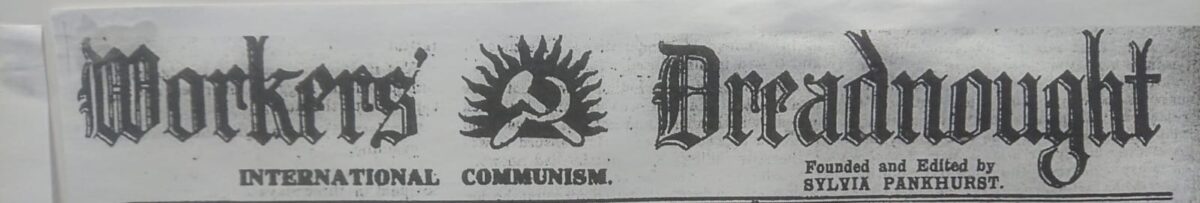

She remains thoroughly radical, setting up solidarity committees against Mussolini and with the Ethiopian resistance against the Italian invasion together with her partner, Italian anarchist Silvio Corio. You can get some insight into this at a little exhibition currently showing at Charing Cross Library, which focuses on that link between Sylvia and Silvio. And that helps you understand a bit better how Sylvia linked working-class struggle through her newspaper Workers Dreadnought with anti-racist and anti-colonial struggle, and then how and why she ended up living in Ethiopia toward the end of her life.

That missing third act might pick up in more detail the political trajectory of Sylvia and emphasise, much more than the musical does, how she was far to the left of her mother, Emmeline Pankhurst, who stood as a candidate for the Tory Party, and her sister, Christabel, who also shifted to the right. There were black suffragettes then, and we could actually have seen more of that. Then you might get a better sense of the way Sylvia’s struggle for the vote for women was grounded in working-class struggle. You’ll get something of that, but not as much as we would have liked through the Old Vic production.

Final thoughts

While we may not have had a pitch-perfect political message in the production, we did have the staging of women’s struggle as well as the struggle of all of the oppressed in performances that re-embodied Pankhurst’s work. This was a progressive and thoroughly enjoyable experience, leaving its audience energised and, we think in many cases, hungry to find out more about the lives and struggles it portrayed.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Protest Review Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women