Robert Chapman’s book The Empire of Normality: Neurodiversity and Capitalism is very different from most of the tame critiques of psychiatry you will find in psychology textbooks, underlying assumptions from which find their way into much chatter about psychiatry and “anti-psychiatry.” The story usually frames the issue as being about some developing ideas about the difference between what it is to be healthy and what it is to be pathological. There is often a little hand-wringing about how this has been a little too crude – a bit too racist and sexist, for instance – followed by a reassuring narrative about advances in medical science and more tolerance for people who find it difficult to adjust to modern life.

There are some crucial underlying assumptions about brain structure and chemistry in those mainstream accounts that enable psychiatry as a medical speciality and psychology as a discipline concerned with good behaviour and right thinking to carry on as normal. And when “anti-psychiatry” is discussed, it is to show us that those folks – Thomas Szasz and R D Laing are the usual suspects wheeled out as case examples – made some good points but mainly got it badly wrong; anti-psychiatrists, so the story goes, didn’t really take distress seriously, even romanticised “mental illness,” and so we need to go back and search for the reasons why some people cope and others fail.

Neurodiversity against capital

Robert Chapman shows us that we need to take a step back with “neurodiversity theory” as a way of making sense of this in order take a different direction through this mess, the miserable mess that individuals find themselves in when they end up in front of a psychiatrist and the miserable political-economic mess that makes so many lives intolerable. This is an avowedly materialist way forward that is also bravely and deliberately intersectional, taking seriously dimensions of oppression – of race, gender and sexuality – in order to make an argument about how capitalism enforces normality, disables people and then blames them for their “disability.”

Tying different dimensions of exploitation and oppression together, their claim is that “the idea of the ‘normal’ person, brain, and mind has been intimately intertwined with colonialism, imperialism, and white supremacy,” and you need Marxism to understand how and why that is the case. They show how capitalism, a system of rule that has always required that workers conform to a norm so they can sell their labour power and adapt to systems of mass production that will yield the most profit, has stepped up its attacks on those who do not and will not fit in, and has extended the reach of this “normalisation” of behaviour to how we think and feel; there is a sustained shift under capitalism to what Chapman terms the “neuronormative.”

Anti-what?

Along the way they make some telling points not only about psychiatry but also so-called “anti-psychiatry” as a supposedly anti-normative and apparently progressive alternative. There are some useful reminders here in the book of the big political difference between Szasz and Laing. Szasz was trained as a psychiatrist (and psychoanalyst by the way) who railed against the medical model from the right; his was a reactionary attack not only on what mainstream psychiatry did to people but also on anyone who used psychiatry labels as “excuses” for bad behaviour. This, of course, is a dangerous line of argument that impacts on anyone who wants to reclaim the labels they have been given and find a way of using them to find support.

The “neurodiversity” movement, for instance, will include many activists who are critical of labels like “autism,” say, but who find in the descriptions of experience that the labels point to something useful for making sense of their lives and arguing for safe spaces and therapeutic help. Chapman is arguing here for an alliance of those who are “neurodiverse” – and the term is inclusive of all forms of difference – with anti-colonial and queer and many other movements that are fighting for space to be heard and, if they are heard, would reenergise the left, reenergise anti-capitalist resistance.

But what of the apparently more politically “radical” left-wing “anti-psychiatrists” like Laing. Here Chapman is wiser than many Marxists who think Laing is one of their own. Yes, it is true that Laing was not a rampant individualist like Szasz, but Laing, who was trained as a psychiatrist (and, yes, also as a psychoanalyst) was wedded to a kind of liberal existentialist position that ended up letting capitalism as such off the hook. Basically, even in its “left” version, most anti-psychiatry is concerned with mainstream medical approaches as mistakes that can be corrected by educating people, helping them see that the problems come from labelling and so, if they ditch the labels all will be well.

Back to Marx

What “Neurodivergent Marxism” gives us is an extended critique of the real underlying problem, which is capitalism as a system of normative production and consumption that either enforces “normality” – in its worse extreme cases, wiping those designated “abnormal” out, incarcerating or even murdering them – or attempts to incorporate them as market niches or token well-being “experts by experience” who can soothe the mental health system and help it run more smoothly.

As Chapman points out “many workers today perform cognitive, attentive, and emotional labour more than the manual labour of Marx’s time,” and so we need to grasp the ways in which neoliberalism or present-day “neuroThatcherism” conflates normality with productivity.

This book draws attention to the impact of the “increasingly intense cognitive needs of capital” on mental health and “disability,” expanding the way we conceptualise alienation and the deep neurological levels to which the “psy” professions are engaged in reimagining our bodies and brains as machines.

History lessons

The book ranges over the history of medicine and the role of Francis Galton and Adolphe Quetelet on the production of “averages” and so also, as a flip-side of the “average man,” the “subnormals” who failed to make the grade. Chapman’s Marxist history of normality and abnormality then gives us a quite different frame to understand how early psychiatrists like Emil Kraepelin could come to claim, and this is a quote from the great psychiatrist himself, that “an everwidening stream of inferior stock [is mixing] itself with our offspring, [contributing] to the deterioration of the race.” So Chapman gives us scorching critique and a history lesson that every student of psychiatry and psychology should now be reading.

There are comradely quibbles I could have with the book. It is unfair, for example, to claim that Marx is also implicated in the labelling of those who depart from the image of the “average worker,” – and so “directly influence by Quetelet”, Chapman says – for Marx was actually also showing how that “average” was part of the normative and adaptive system of production he was intent on overthrowing. Neither do I think it is right to say that “Freud saw mental illness as stemming from the upset equilibrium between conscious and unconscious drives.” For Freud, we are all “abnormal,” and though there were deep problems in some of Freud’s work – he was no Marxist, for a start – it is possible to take that argument about the abnormality of us all as being potentially in line with a practical critique of what Chapman calls “the empire of normality.”

Critique and action

Apart from anything else, this is a valuable primer in radical disability theory, enabling the “social model” to encompass and enrich the “neurodiversity” paradigm. This is a critique and a call to action. Yes, “society requires diversity,” and so this brings those who are made “surplus” to needs of capital in order to build that society as an alternative to capitalism, this because “the interests of the working class and the interests of the surplus class are one.” This all poses a challenge to anti-capitalists to develop, as Chapman puts it, a “transitional politics that centres the surplus and, crucially, finds ways to empower the surplus as surplus” for a “neurodivergent praxis” that is intersectional and “internationalist.” We should learn from and debate with this book, with what this comrade brings us.

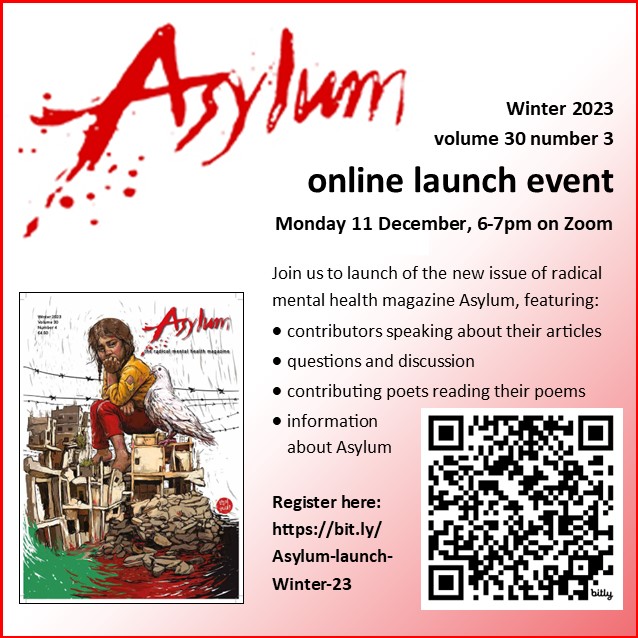

A version of this review has just been published in the latest issue of Asylum, The Radical Mental Health Magazine, the issue launch for which will be online on Monday 11 December.

Art (54) Book Review (125) Books (114) Capitalism (68) China (81) Climate Emergency (99) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) EcoSocialism (57) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (61) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (71) Gaza (61) Imperialism (100) Israel (127) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (55) Labour Party (113) Long Read (42) Marxism (50) Marxist Theory (48) Palestine (175) pandemic (78) Protest (153) Russia (341) Solidarity (145) Statement (49) Trade Unionism (142) Ukraine (349) United States of America (133) War (368)

Have you read Laing, Ian Parker? When did Laing let capitalism off the hook? Where is evidence of his “liberalism”? And is it necessary that one be a Marxist to be a social critic?

I notice that you didn’t cite a single work of his in this article. Very sad stuff. Laing’s writing is of more value than any ideological screed ever could be.