On 23 August Extinction Rebellion began two weeks of action in London against the government’s continued support for fossil fuels, especially the planned Cambo oil field west of Orkney, and the Cumbria coal mine near Whitehaven, in the run up to the COP26 conference on climate change.

The start of the XR action was immediately preceded by flash floods in Tennessee and a giant tropical storm on the US East coast. The flash floods and huge storms across the world this summer are all directly linked to warming seas and global heating. Like the connected wildfires, they will only get worse unless global temperature rises are limited by a sharp reduction and eventual elimination of the burning of fossil fuels. Next week the XR actions will move on to the City of London, site of the London Stock Exchange, where an estimated 30% of company value is linked to fossil fuel capitalists.

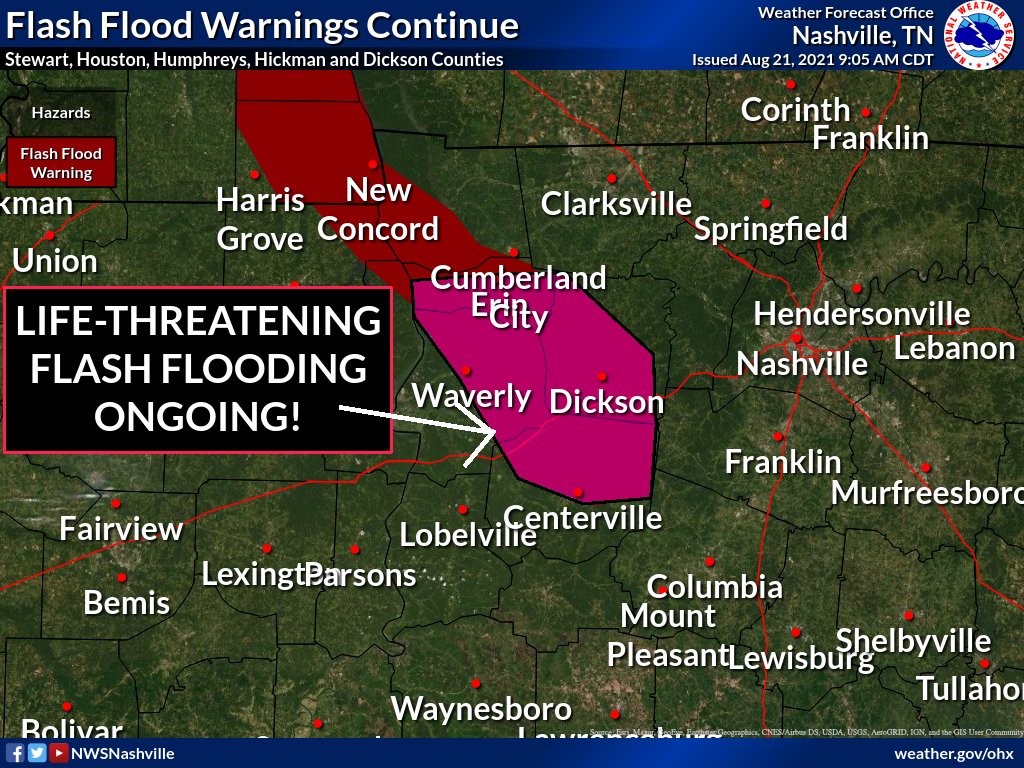

On August 21 flash floods hit the small Tennessee town of Waverley, destroying many of the dwellings in Brookside, an area of mainly public housing. Last reports said there were 22 dead and that dozens are missing. Not that you would have noticed from the BBC 10 o’clock news the next day, because it was not reported, although tropical Storm Henri approaching a wide area of the east coast was covered. Both events have the same source—rising sea temperatures, which ironically are also the main cause of the devastating wild fires in the Mediterranean and Siberia this summer. These fires have badly damaged Turkish holiday resorts like Antalya and Bodrum and ravaged mountain forests as far away as Algeria. Rain and fire go together in the new global heating crisis. More than 1000 people have died in flash floods internationally this summer.

Property developers and real estate agents are among the venal sections of the capitalist class. Now they have come up with a predictable response to the climate crisis—gentrification. The form this gentrification takes is driving poor people out of areas on higher ground, less vulnerable to flooding and tropical storms, forcing them to give up their rented properties, or sell properties they own, to the rich.

One huge exercise in climate gentrification has already occurred, in New Orleans after the disastrous 2006 flooding. A key form of gentrification was the simple taking over of working class, mainly Black, neighbourhoods by property developers, after the residents moved out, their properties wrecked and uninsured, making return by their original owners impossible.

But then a second wave of gentrification followed as poor and Black families go, priced out of houses that survived the flooding. CNN reports the case of Ross Dyson, a middle-aged woman who lived in a house on high ground, paradoxically near the Mississippi river, driven out of her house by the increase of her Property Tax Bill to $4,000 dollars a year. Ironically the tax is based on the value of the houses in the area, effectively much like the system in the UK. Houses on high ground shot up in value as richer, white people moved in, further pricing out poor people who had been fortunate enough to survive the 2006 flooding. Before the flooding, Ross Dyson’s area was 79% Black, now it is 71% white.

Climate change gentrification is also coming to Miami. The city has recently experienced floods caused by hurricanes and other tropical storms, and the worst effects are along the shore line. Rich people want to move out and upwards, away from their previously highly desirable shoreline properties, and have moved into the area known as Little Haiti, where immigrants from poverty stricken Haiti are struggling with rising rents and annual property charges. As the example of San Francisco’s gentrification shows, these rising charges hit small businesses as well as family homes, changing the whole nature of many localities, driving out small shops and restaurants and replacing them with Starbucks and McDonalds.

Moving away from easily flooded areas is becoming a global phenomenon, but in many areas this is going to be impossible for the poor or city workers. In any case, exactly where flooding is going to be is hard to calculate. For example the risk of flooding in London can no longer be limited to the Thames and other rivers overflowing their banks. The August flooding in the London district of Walthamstow, on relatively high ground, was nothing to do with its proximity to the nearby River Lea, but everything to do with insufficient drainage to deal with flash flooding.

On July 25, nine London tube stations were forced to close by flash flooding. Commuters at Covent Garden and Pudding Mills Lane on the Docklands Light Railway were suddenly faced with torrents of rain passing through the station and swamping tricked barriers. The heavy rain causing the July 25 flash floods was a brief spell in the middle of a long heatwave—a typical cycle that is similar to the weather during the early July flooding of North Rhine Westphalia and Rhineland Palatinate, which killed, together with casualties in Belgium, more than 300.

British weather in 2020 showed how the climate is changing: a report by the Met Office found that 2020 year was the third warmest, fifth wettest and eighth sunniest year ever recorded. Heatwaves and devastating floods go together.

The interaction between extreme heat and extreme rainfall is going to be different in different parts of the world. As the Sahara Desert marches northwards to attack the Algerian coastal hills and the Greek countryside, heat is likely to outdistance rainfall. But in places like Northern Europe, extreme heat and extreme rainfall are likely to closely interact.

Germany, the Netherlands and Belgium were not the only places experiencing extreme rainfall this summer. More than 300 people died in flooding in central China, mainly in the city of Zhengzhou, where 14 people were drowned in a subway train carriage from which they could not escape.

What should be the response of the environmental and socialist movements to flash flooding? The events this summer show there is no overall solution outside directly tackling the issue of global heating, and that means hitting emissions targets, replacing fossil fuels with sustainable alternatives like wind power. But that is a long term project that cannot be rapidly solved. We need practical solutions in the here and now to help the victims of flooding, who, as New Orleans showed most dramatically, are likely to be the poor and working class communities.

The first issue in the UK is land and flood management. This involves tree planting, restoring peatland but also flood water management—and that means paying farmers to store flood waters on their land. The alternative to this is that all the flood water goes into rivers and causes enormous flood pulses downstream that sweep into towns and villages with drastic effects.

Land and flood water management won’t stop all floods heading towards towns and cities, so flood defence schemes are vital. The government has announced a £5.2bn flood defence scheme, but we will see how much is built. Most of these schemes suffer from the disadvantage that they defend one community by pushing the problem down to the next one.

The third question is urban drainage. Much of the drainage in British towns was build during the great period of municipalisation in the second half of the 19th century. Towns and cities are now much bigger and a huge process of replacement is needed, costing many billions.

The fourth issue is insurance. It is impossible to get insurance in many flood-wrecked areas. As houses, furnishings and belongings are damaged, some households have faced huge bills on an annual basis. Insurance companies must be compelled to actually insure their clients rather than getting rid of them when they put in substantial claims. This process affects numerous businesses and householders, for example the hundreds of thousands who live in properties affected by subsidence, whose insurance companies regularly find ways of avoiding payment.

Often studies of the inundation threats from global warming have focused on rising sea levels. But flash floods are part of the same process of global heating as is the increase in the number of tropical storms. This is mainly the warning of the sea.

As numerous commentators have pointed out, the British government which is hosting the COP26 conference, is long on targets and promises and short on action. The proposed Cambo oil field is a giant enterprise that would mean Britain producing and exporting oil for decades. The argument that we need fossil fuels as we transition to green power is a con, reflecting the enormous power of the fossil fuel capitalists who will be targeted by XR action in the City of London next week.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Protest Review Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women

“The argument that we need fossil fuels as we transition to green power is a con” is only true if we in the wealthy societies of the world are willing to immediately drastically reduce our energy use. There is no way that even our current total energy use here in the UK can be supplied by renewables, let alone that in the future with increasing population and a switch to electric vehicles, electric heating and electric everything else. Unless the author knows more than I do, which is quite possible, fossil fuels will still be needed for decades to come without a massive political, societal and economic revolution towards socialism. Is that seeming likely right now?

One way to reduce our energy use is to move away from individualised mass transport via private automobiles towards free-at-the-point-of-use public transport, at a local and regional level. EVs do not produce CO2 or NO2 emissions at the point of use that is true, but they do produce particulate pollution from tyres and brake, they would use an awful lot of energy if mass produced, they are heavier than normal cars and would necessitate more road repairs, they demand large amounts of minerals for the batteries (so more extractive industries), and the vast amount of electricity that they would need could not be met renewably. Moreover, they would do nothing to ease congestion and delays. Apart from specialist use, such as for disabled people, private cars have had their day. Emissions from surface transport are huge in the UK and are rising. This is unsustainable. Fare Free Public Transport (as practised in about 100 cities worldwide) is one important strand in reducing energy use.