Source >> rs21

What is CASWO and when did it get started?

Care and Support Workers Organise (CASWO) is a campaign across Britain for bringing together care and support workers to fight for better conditions. The campaign started in March 2020, following a Unison call that brought together care workers to discuss Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). There’s an idea that every care worker works with elderly people. This isn’t the case – a lot of people work with disabled people, and some of it is support work. So not every care worker was used to wearing PPE when the pandemic hit, and many of us just didn’t have access to it. On that call, there were care workers in London who’d been given a single surgical mask to go and see 20 people in the same day. So there was a lot of information and skill-sharing, because we were being hit with government guidance and it felt like we were going into the abyss. Not only were we afraid for ourselves and our families, we were afraid of not giving the best care to the people we were there to support.

After that call, it was very evident that there was a need for us to organise cross-union. Density is low in the care sector, so there was an understanding that we need to work together to support the sector as a whole. Care and support work is spread across the public sector, the private sector and the third sector, and unions themselves have problems dealing with that. However, they’re the same jobs with the same problems. So CASWO was formed.

What have been your daily activities in CASWO since you started?

After the lockdowns, we came up with eight clear demands and tried to lobby, mobilise and organise around them. The demands are around pay, fair contracts, sick pay, health and safety at work and various other key things that would improve work for care and support workers and the people who use our services [see the full list of demands on CASWO’s website here]. We are also really keen on gathering information and stories and reporting to the Health and Safety Executive, and using our trade unions to amplify our struggles, and supporting each other to do that. Trade unions are big bodies and if you haven’t been engaged with them before, they can be hard to navigate. We also support each other in getting union recognition and help each other organise in our workplaces.

We were also instrumental in lobbying for care and support workers to be counted as keyworkers in London, which, due to policies spearheaded by London Mayor Sadiq Khan, now gives them access to ‘affordable’ housing. The fact we’d been cut out of that shows how invisible a lot of our work can be. We had cross-party support for that change because of the arguments we put forward.

One of the other demands is around sectoral bargaining and the creation of a National Care and Support Service that meets the needs of the people we support. CASWO is absolutely in solidarity with disabled people, because we know that the care and support we provide is not good enough. That’s not because of our lack of compassion or effort. It’s because of a system that is underfunded and where people who use services have been ignored – their rights have been ignored, their voices have been ignored, and the power dynamic when delivering services has been ignored.

What trade unions do you work across, and which trade union should any care workers reading this article join if they aren’t yet in a union?

Well, definitely join your most relevant trade union! That’s absolutely critical. We work across unions that organise in care, like Unite, Unison and United Voices of the World (UVW). Our battle is not about which union you should join. Either join the union that is pre-existing in your workplace, or speak to your colleagues about what union is the most relevant. If you work in a care home that is owned by a singular owner, you might want a flexible union in which you can unionise quickly and not engage with the bureaucratic structures. This might mean UVW is the most appropriate – they have organised to amazing effect at the Sage nursing home in London, for example. However, if you are working in Four Seasons, that’s a huge organisation which owns hundreds of care homes. You’re not going to win better terms and conditions if only one of those care homes goes on strike, so you’d need a larger union that has the power to unionise and organise across sites.

What’s your favourite moment in CASWO so far?

A lot of my favourite moments have been where we, as care and support workers, have come together to show each other care. Last year, several of us went on a retreat together to discuss issues facing the care sector. If you’re on minimum wage, it’s difficult to have a holiday, so this was the first time some CASWO members had met each other; we’d been organising for years over Zoom. It was a really nice chance for us to be together and support each other.

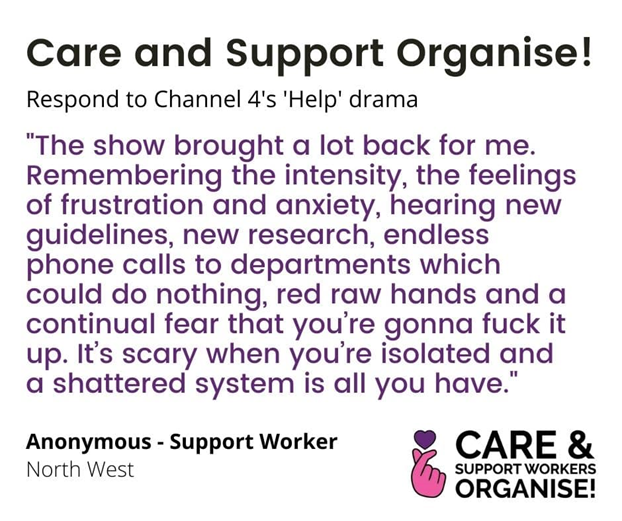

We had a meeting after the Channel 4 programme Help had just come on the TV, and it was in the media. We had a Zoom meeting where a group of care workers spoke about how the pandemic had affected us. We shared our stories and it was emotional – the personal is political. Lots of people died during that period – people’s colleagues, friends, people they support. But also we were all struggling against a broken system that treated us like shit.

I also appreciate it when supporters who don’t work directly in care and support join us for particular actions. We have organised demonstrations, and it’s great to see our allies come together with us to demand change. We work closely with Keep Our NHS Public (KONP), for example. We support SOS NHS, because we know we are part of a system including the NHS which is being eroded systematically by our incompetent government.

Why do you think that care and support workers get such low wages and poor conditions?

I would say because, bluntly, it’s women’s work. It’s social reproductive work. Instead of making profit directly, it reproduces our society. We see a lot of women and migrant workers take on this labour, and also a lot of part-time workers with caring responsibilities outside of work. It’s invisible labour: there’s no product at the end that can be sold on a market. So it has always been undervalued because we’re in a capitalist system that expects care to be done for free.

I also think, because of the subcontracting and fragmentation, there is no muscle memory of unionisation in the care sector. The fact it’s so fragmented and atomised makes it incredibly difficult to organise, so unions struggle, which has the long-term effect of depressing wages and conditions.

Thinking about this last year, how is the cost of living crisis affecting care and support workers?

The cost of living crisis is massively affecting care. We are seeing an exodus from care and support services. We saw this throughout the pandemic, it was happening before the pandemic, and now it’s ramped up. Some organisations are facing between a 35% and 50% turnover rate per year. It’s a churn that affects the ability to organise and create lasting structures of organisation in workplaces. We are experiencing a labour shortage following Brexit, and because these jobs are low-paid and low-valued.

In London, care work is disproportionately carried out by migrant workers. Migrant workers are subject to hostile environment policies – and why would you work here when the rate of inflation is so high and your wages aren’t going up?

We are starting to see Tory government recognising that there is a staffing crisis in care, and there are new proposals for Health and Social Care visas to enable health professionals to come to the UK legally. But these proposals are extremely stringent, and I can’t see them helping. If you want to come and work here for peanuts, you have to have a certain amount of money to even come into the country – right now it’s £1,270 that you have to have available for 28 continuous days before you apply, and there’s an application fee of between £247 and £479. That’s a lot, especially if you’re applying from somewhere with a currency that doesn’t have a good exchange rate with the pound.

How would you say that the care sector is changing under neoliberalism and how is that affecting workers?

I think that the financialisation of care is a big factor. In care, we have the Big Five, and increasingly care is run like big business. The different opaque business models that are taking over care provision are scary. I recommend the work of Dr Amy Horton, who writes about REITs – Real Estate Investment Trusts – whose business model is buying up care homes and doing them up into plush hotels, and then creating a different arm for the care provision. In these systems, the buildings are made with the expectation that the care business might fold anyway, and they can be easily transformed into cheap hotels or other more profitable forms of business. It’s a really unstable model for care work.

An example that Amy Horton writes about is a dementia ward, where instead of thinking about the best way to deliver care and support, they built four identical wings in a kind of super-hospital. If you have dementia, imagine how distressing it would be if you find yourself in a different wing that looks exactly like where you live, but everything’s a bit different. They weren’t considering the needs of the people who use the service, who might feel less distressed if there are recognisable entrances and surroundings. But they have also not considered the workers, for whom managing that distress is an additional burden of emotional labour. None of the design is tailored towards delivering the best service; it’s tailored towards profit.

[You can watch Amy Horton speaking on the financialisation of care below]

I know that one issue CASWO took up was mandatory vaccinations, and you did some work with Greater Manchester Law Centre to help care workers understand their rights. Why was this such a key issue for CASWO and how do you think the unions handled it?

In late 2021, the mandatory vaccination was introduced for CQC-registered care home staff. I’d estimate that tens of thousands of workers got summarily dismissed because of their vaccination status. This legislation has now been revoked, but the damage was done.

The big unions did come out against mandatory vaccinations; however, there was no coordinated action around it. As CASWO, we walked a fine line of being against mandatory vaccinations but incredibly pro-vaccine. We worked with the British Medical Association and held confidential groups for care workers to try and tackle vaccine hesitancy. There were a lot of care workers who were sceptical, many from migrant backgrounds who have past trauma of state healthcare, both here and abroad. There was a deep and understandable distrust of the NHS. I used to be a mental health worker in Hackney, and I met people who were sectioned because of talking to themselves in the streets, and then had to bust themselves out of psych units. People of colour are far more likely to be detained under the Mental Health Act than white people. I can understand hesitancy if those have been your experiences. When you are sectioned, you lose pretty much all your rights.

Because of the lack of response from the unions, other organisations who are much more insidious have stepped in to fill the gap. There is now a right wing organisation called the Together Declaration, with a real libertarian flavour. Like CASWO, they were calling to reinstate and compensate workers who lost their jobs because they didn’t get vaccinated in time, but they are arguing for it on the level of individual rights, rather than collective power. I think they’re using people to further their political agenda which I think is dishonest and opportunist, but it’s the unions that have given them their opportunities. When our unions do nothing, this is what emerges to fill the gap.

There was also the creation of a right-wing union called Workers of England who did oppose mandatory vaccination, and a large number of care workers joined it. They promised that if you joined the union they would offer individual legal support, get your claim into the Employment Tribunal etc. But this is absolutely a service-based union that doesn’t believe in collective organisation. I don’t believe they care about care workers: they’re not going to back better terms and conditions, better pay, or union recognition.

Thinking about fighting back, is there any particular industrial action you’d like to raise that is currently ongoing?

There’s a really important strike going on at the moment, and that’s amongst Unite-organised support workers at Hestia in London. I think they’ve had four or five days strike action already. They have been raising some really interesting questions. We spoke earlier about a lot of the workers in care being migrant workers. One of the things these workers were raising is that the employer is using their translation and interpreting skills for free. These are incredible workers with skills above and beyond their job description, and their language skills are being used at no cost to their employers without any recognition of that in their wages.

Another demand was about understaffing. The mass exodus from care has a massive impact on workers, whose workloads are increasing and jobs are getting more complex – and then you’re trying to cope on a shift with five workers not seven.

Of course it was also about pay – I think they were demanding over the real living wage. However, the things they brought to light included the invisible labour they were doing. As a care or support worker, not only do you do what’s in your job description, you are a translator, a therapist, a debt advisor, because the state has crumbled.

It’s a David and Goliath situation because Hestia are huge; they’re all over London. But there’s one small bargaining unit in that who are saying no. They’re not only courageous, but their skills are so much more valuable than is recognised by whichever Tory twat is calling us unskilled this week. Pick your villain.

What can we be doing to show solidarity with care workers this year?

The thing for care workers is that it is almost ingrained into our psyches that we cannot strike.

I recently visited a respite care home. I spoke to the workers there, and even though the ambulance workers, nurses and doctors were going on strike or considering it, they felt that their work was so important that they couldn’t. Care workers often feel that their work is different because of the longevity of the relationships and the deep connection with the people they support. They supported the other workers, like the nurses – they just couldn’t reframe their own jobs to convince themselves that striking is an option for them. We need people from outside saying ‘we wish the care workers were going on strike, and we will back you’.

Subscribe to updates from CASWO on their website here, or follow them on Twitter, Instagram or Facebook.

Alison has worked in the care sector for 15 years. You can read more about her experiences of care work during the pandemic in her article for Spectre here.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women

The Anti*Capitalist Resistance Editorial Board may not always agree with all of the content we repost but feel it is important to give left voices a platform and develop a space for comradely debate and disagreement.