Visiting this show, you are welcomed into the imagined community of black people that Yiadom-Boakye has created with her bold, expressive brush strokes and vibrant dark colours. These are big pictures that dominate the gallery rooms. Unlike most portraits, not one of these eighty portraits is of an identified person. Nobody sat down in her studio for days on end for her to paint. She creates her own world of people from photos, pictures, and other sources. Yet each picture is real and human enough for you to relate to it immediately.

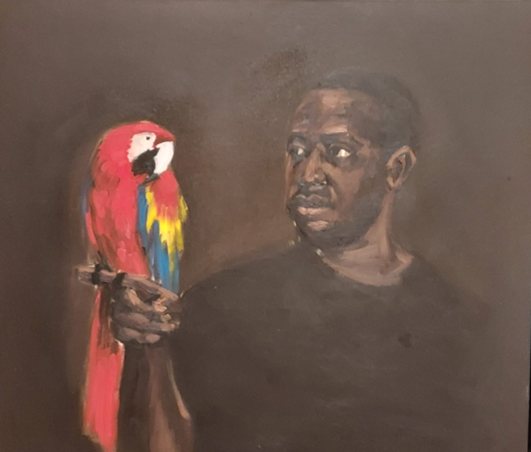

The attention is almost exclusively on the figure. Unlike the traditions of this genre in the 18th or 19th centuries, they are not placed in a landscape, their homes, or their workplaces. A few pictures place the subjects on a beach without any real horizon or depth. Sometimes birds or cats are added to the picture, or there is a flamboyant costume. The warmth or coolness of her colours suffuses the subjects and provides a feeling that captures the person as much as the form or composition. Just a few subtle brushstrokes of white bring the people to life amid the dark tones. Although the tones are often subdued, some paintings (see above with the parrot) have explosions of bright colours that leap out at you.

There are no direct political or social references in her paintings. However, because commissioning a portrait required money, the portraiture tradition in art is almost always of white aristocrats or bourgeois people. Having your portrait done was part of asserting your social status. Often, it included landscapes, houses, or objects that represented your wealth. So a show that only has portraits of black people inevitably has an implicit ideological or political meaning.

Yiadom-Boakye also writes prose and poetry, and the titles of her works are allusive and imaginative, challenging the viewer to question what they see.

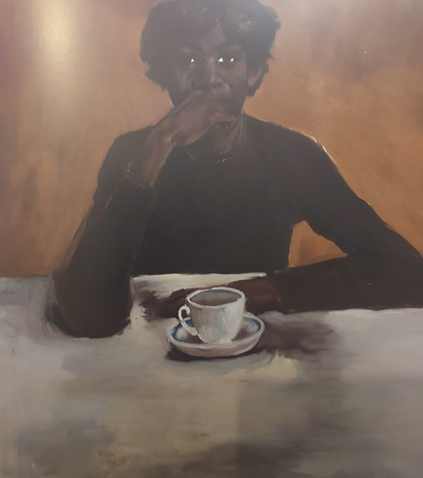

For example, this picture is entitled “No Such Luxury” (2012), and it immediately gets you thinking about the life of this woman in front of her cup of tea or coffee. Her face with the hand over her mouth seems to suggest she is thinking about some difficulties or concerns. Her life is not easy; there is no luxury. Of course, the beauty of these works is that another viewer might see something different. One reviewer suggests that this picture is equivalent to Magritte’s picture of a pipe with the title, “This is not a pipe,” but here it should read, “This is not a portrait.” Yes, these pictures are much more than a mere record of someone.

We loved this picture, “Hard Wet Epic” (2010). The range of colour is quite limited—various shades of browns and blacks—but the composition and details on the faces communicate a sense of movement, enjoyment, and fun on a day at the beach. Most of the pictures are of one person, but some of the group pictures capture really vivid moments. Consider “Condor and the Mole” (2011), one of the few images with a landscape and two young girls. Mostly black, white, and brown, but the red and blue of the dresses just bring it alive; you can feel the excitement of the kids playing on the beach, dipping their feet into the wet sand, finding new things.

We calculated that roughly eighty percent of the subjects are male. Dominant ideology often reproduces images of black men as violent or aggressive in films and TV shows. Placing birds or cats with them has an effect of care and calmness. Look at this picture. Here there is softness, tenderness, and a sexual allure.

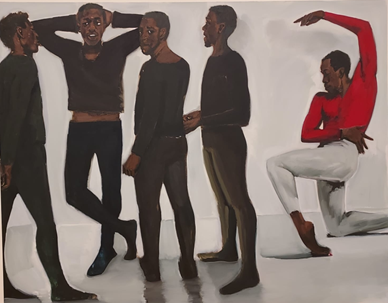

The pictures that show men in groups are in a similar vein. Friendship, solidarity, and conviviality stand out. Sometimes you can work out the situation; other times it is more difficult. This looks like some sort of dance studio. The painter uses colour again to strike a contrast between the group on the left and the dancer practising his move on the right.

Born in 1977 in London, Yiadom-Boakye’s work goes against the current of much modern art, which is not very figurative in general and does not include a lot of oil painting. However, she shows how you can still use such an approach to produce art that is accessible and original. Although her show finishes on the 26th of February, her works can be viewed online, and there are currently videos of talks she has given that can be accessed for free.

Jonathan Jones gets to why these portraits work so well in his Guardian review:

she reveals that a picture of someone can be so much more that the banal record of her, him, they – so much more than a selfie. These are paintings of states of being, states of the human soul.

LYNETTE YIADOM-BOAKYEFLY IN LEAGUE WITH THE NIGHT until 26 February at Tate britain

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War