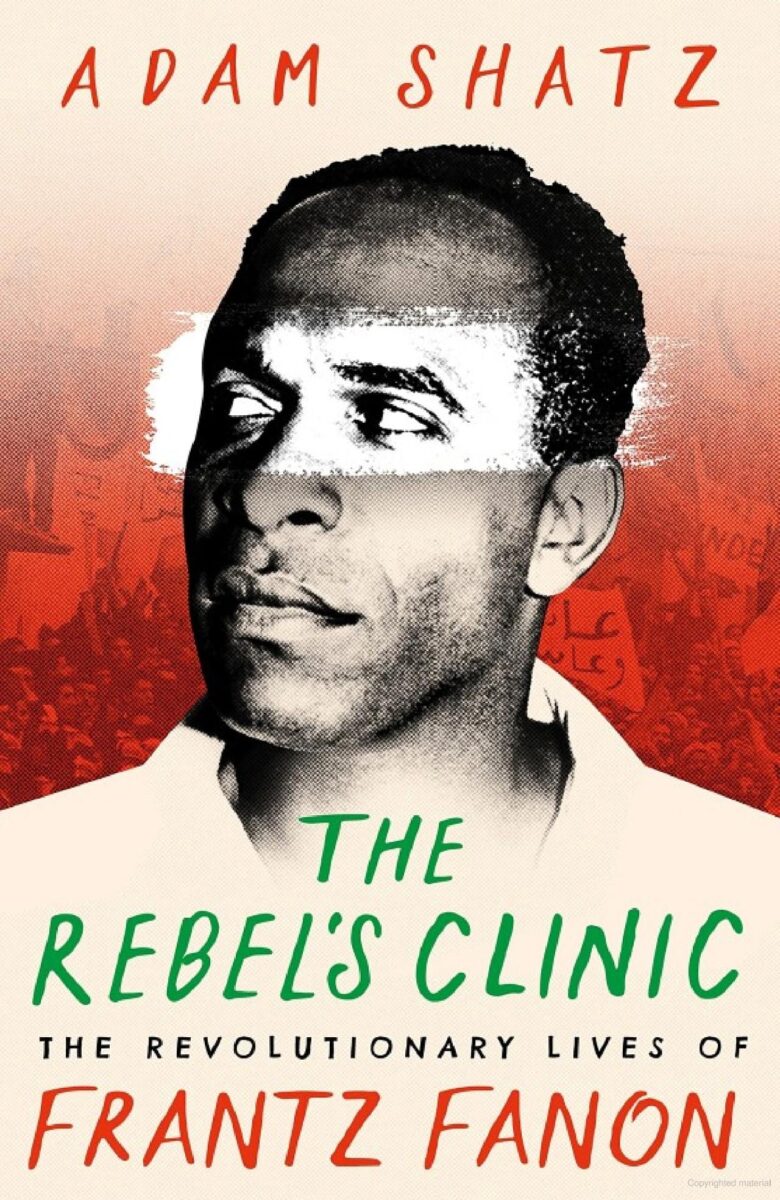

Frantz Fanon was once known as the “Lenin of Africa,” an inspiration for liberation movements on the continent and then across the world as anti-colonial struggle took centre stage. More than that, he tried to link personal and political liberation in his clinical work, to understand the psychological depths of racism and forms of resistance, and then shifted his focus to directly work for Algerian independence, expanding his analysis from North Africa to the whole continent. A key focus in his theoretical and practical work was on the role of violence under colonialism and in the process of liberation. This new book, The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon by Adam Shatz, published last month (Bloomsbury, January 2024), provides a detailed and helpfully critical account of this remarkable revolutionary.

Life and impact

Frantz Fanon was born in 1925 in Fort-de-France, capital of the island of Martinique, a French “department” in the Caribbean, a colony, still an integral part of France today. During the Second World War the island was under the “Vichy” regime as part of the collaboration with the Nazis, and Fanon left the island to fight fascism. He was decorated for bravery, and rewarded with a bursary after the war to study medicine and train as a psychiatrist in France.

Adam Shatz traces through the journey from Martinique, from a colonial context in which gradations of “Blackness” were used as a tool of oppression, to France where Fanon encountered direct racism first-hand, something he wrote about. Now, as a “French” radical, he worked within medical psychiatry and questioned it, working with some other radical psychiatrists, including those who sought refuge from fascism in France and Spain. A lesson he took to heart was about the interrelationship between forms of oppression, and the way that colonial power maintained its grip through divide and rule, a lesson voiced in advice by a colleague that “When you hear someone insulting the Jews, pay attention, because they’re talking about you.”

Fanon was then appointed to the psychiatric hospital in Blida, just south of Algiers, and it was here that he began to identify with the Algerian liberation struggle, directly aiding fighters from the FLN, the Front de Libération Nationale, while at the same time trying to introduce alternative forms of clinical treatment. Here he attempted to take forward the “institutional therapy” he had learned during his training in mainland France, a kind of therapy that treated human beings as social beings, always in context, in relation to others. It is here that Fanon becomes a self-identified Algerian revolutionary, and his classic, part autoethnographic study, Black Skin, White Masks, published in 1952, tackles the way that racism works its way into the internal lives of the colonised and colonisers. There were signs on the beaches of Algiers and Oran that read “no dogs, no Arabs.” Algerians were seen as less than human, and they were encouraged to internalise that image, seeing themselves as brutes rather than human beings.

“Here he attempted to take forward the “institutional therapy” he had learned during his training in mainland France, a kind of therapy that treated human beings as social beings, always in context, in relation to others.

Violence

Fanon has now experienced fascist violence and colonial violence, and he is noticing how liberation struggle is also, of necessity, also violent, a counter-violence that not only opposes forces of oppression but also gives rise to healing personal and collective agency. The colonised human being emerges in the course of violent political struggle, from being a mere object to being a revolutionary subject. Violence is, in this way, part of a progressive political process but, as Shatz points out, it is also a symptom of a problem, part of the reproduction of colonial violence that is, in some ways, self-sabotaging. There is, Shatz points out, a tension for Fanon “which he never quite resolved, between his work as a doctor and his obligations as a militant, between his commitment to healing and his belief in violence.”

The argument about violence is made most forcefully by Fanon in a book that was immediately banned in France on publication in 1961, The Wretched of the Earth; in French Les damnés de la terre (which evokes, among other things, lines from The Internationale). There had been massacres in Algeria of hundreds of colonists (events that the French Communist Party was quick to denounce as “Hitlerian”), and then reprisals in which thousands of Algerians died. It was actually the preface by Jean-Paul Sartre that hyped up Fanon’s nuanced and contradictory exploration of violence, and made it seem as if Fanon was advocating all-out violence as a pure cure-all.

Shatz comments on the wording that Fanon used in The Wretched of the Earth: “The English translation of la violence désintoxique as ‘violence is a cleansing force’ is somewhat misleading, suggesting an almost redemptive elimination of impurities, whereas Fanon’s more clinical word choice indicates the overcoming of a state of drunkenness, the stupor induced by colonial subjugation.” For Fanon, it is in violence that the colonized, and this is a direct quote from Fanon himself, find the “key … to decipher social reality.” However you play it, with all the ambiguities, you can see how central violence is to oppression and resistance.

“However you play it, with all the ambiguities, you can see how central violence is to oppression and resistance.

By now Fanon has resigned from the intolerable situation at the hospital and moved to Tunis where he is working for the FLN and develops a reputation as its chief theoretician. As an ambassador for the Algerian liberation struggle, he is in contact with African revolutionaries, and now claims that identity, as African. He writes other important studies, including on the Algerian revolution and on the African revolution, but his life is cut short by leukemia, and he dies in 1961 age 36.

Contested claims

There are some missteps in the book, in the false claim, for example, that Fanon distanced himself from the French psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan because Lacan celebrated madness as a kind of freedom. That characterisation of Lacanian psychoanalysis is actually quite wrong, and the Lacanian position on the dreadful “unfreedom” of psychosis is actually very close to Fanon’s own position.

“There are some missteps in the book, in the false claim, for example, that Fanon distanced himself from the French psychiatrist and psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan because Lacan celebrated madness as a kind of freedom.

Shatz is very clear about the criminal behaviour of the French Communist Party in relation to the Algerian revolution, and you can see well why Fanon never became a Stalinist; the PCF line was that Algeria was part of France and that the FLN should do a deal. Fanon was never in the Fourth International, FI, but the Algerian liberation movement was a crucial part of the life of the FI in the late 1950s and early 1960s, with the then FI secretary Michel Pablo arrested for gun-running in support of the FLN. Shatz notes that Pablo’s FI operated an arms factory in Morocco (something other leaders of the FI were not so happy about, but which we should now acknowledge as a brave practical achievement).

Pablo wrote about Fanon as a key figure in the anti-colonial struggle; there is much thoughtful reflection by Fanon about the way that a liberation movement that is not explicitly and directly accountable, which does not carry through the socialist tasks of the revolution, risks becoming incorporated into imperialism, with the leadership becoming part of the ruling class of a neocolonial state (as did eventually happen in Algeria). Fanon’s struggle was also ours, and our comrade Daniel Bensaïd has also reflected on his importance for revolutionary strategy.

Fanon now

There is much in this book that resonates with contemporary anti-colonial struggle, including the resistance to genocide in Gaza, and the many ways which colonial institutions attempt to insist only on condemnation of the violence of those who fight back. We are also reminded of the way in which comparisons between the Nazis and other oppressive regimes, comparison that is now treated as a crime in some quarters, was common currency; Shatz notes that “Simone de Beauvoir remarked in her memoirs that French soldiers’ uniforms had the same effect on her that swastikas once did.” Shatz notes that Palestinian psychiatrist Samah Jabr has said of Fanon that “his prophetic insights remain a source of inspiration to Palestinians,” and the recent book Psychoanalysis Under Occupation: Practising Resistance in Palestine is thoroughly Fanonian.

This new biography by Adam Shatz is a really interesting, and beautifully written introduction to, and overview of, Fanon’s contribution to revolutionary politics, and there is much discussion of the link between theory and practice. It is not uncritical, pointing out, for instance, that Fanon had nothing to say about the role of Islam in the FLN political struggle, and, as far as the “clinic” aspect is concerned, it does seem as if the shadow of medical psychiatry was still a powerful influence, not to be copied; Fanon was impressed with electroshock as a “violent” treatment, as if that was also in some bizarre way liberating.

“This new biography by Adam Shatz is a really interesting, and beautifully written introduction to, and overview of, Fanon’s contribution to revolutionary politics, and there is much discussion of the link between theory and practice.

Among other things ostensibly “non-political,” but actually also infused with political meaning, we learn that Fanon liked the bebop jazz of Charlie Parker, and we are given a rich political and cultural context for the “lives of Frantz Fanon”; we also learn that he wasn’t always a hard-faced killjoy, he liked dancing when he had a chance, liked nice shirts with cuff-links and sometimes changed his tie twice a day (though he was a bit reproving when Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir wanted to take him to a fancy restaurant and talk about the food). There is much to learn from in this book, and an opportunity to return to reassess why Marxist revolutionaries at the time engaged with his work, and need to engage with it now.

Art (47) Book Review (102) Books (106) Capitalism (64) China (74) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (43) Economics (36) EcoSocialism (48) Elections (75) Europe (44) Fascism (52) Film (47) Film Review (60) France (66) Gaza (52) Imperialism (95) Israel (103) Italy (42) Keir Starmer (49) Labour Party (108) Long Read (38) Marxism (45) Palestine (133) pandemic (78) Protest (137) Russia (322) Solidarity (123) Statement (44) Trade Unionism (132) Ukraine (324) United States of America (121) War (349)

If you are in Edinburgh https://critique.sps.ed.ac.uk/the-rebels-clinic-the-revolutionary-lives-of-frantz-fanon-book-launch-18-march-2024/?fbclid=IwAR0DRtWY91Txq7PshFxhBueHCKcTxgfwz-vE0fjGASxrgfMdZk6NXU3_QLE

If you are in Manchester: Why Fanon Now 3.30-5.00, Wednesday 20 March, Lecture Theatre A2.6, Ellen Wilkinson Building, University of Manchester. This special session is co-organised by Manchester Psychoanalytic Matrix and the Manchester Institute of Education Power, Inequality, Activism group. We will learn about the work of Frantz Fanon, and its relevance for radical therapeutic and educational and activist solidarity practice today. Guest speakers: Professor Lara Sheehi (Doha Institute) and Professor Stephen Sheehi (William & Mary) (co-authors of, among other books, Psychoanalysis Under Occupation: Practising Resistance in Palestine) and Professor Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian (QMUL, author of, among other books, Incarcerated Childhood and the Politics of Unchilding). The session will be chaired by Professor Erica Burman (Manchester, author of, among other books, Fanon, Education, Action: Child as Method). RSVP to discourseunit@gmail.com

Also Elaine Mokhtefi memories in herBook

and her support forFannon in his fight against his ill health and demise.