I’d written, last week, on the tip-toe towards a form of politics in Britain in which “sacrifices” are expected from most people to meet the rising costs and difficulties of economic life. These will be blamed on the war in Ukraine and, whilst the demands are already coming in for exceptional increases in military spending, the pressure on living standards pre-date Russia’s invasion.

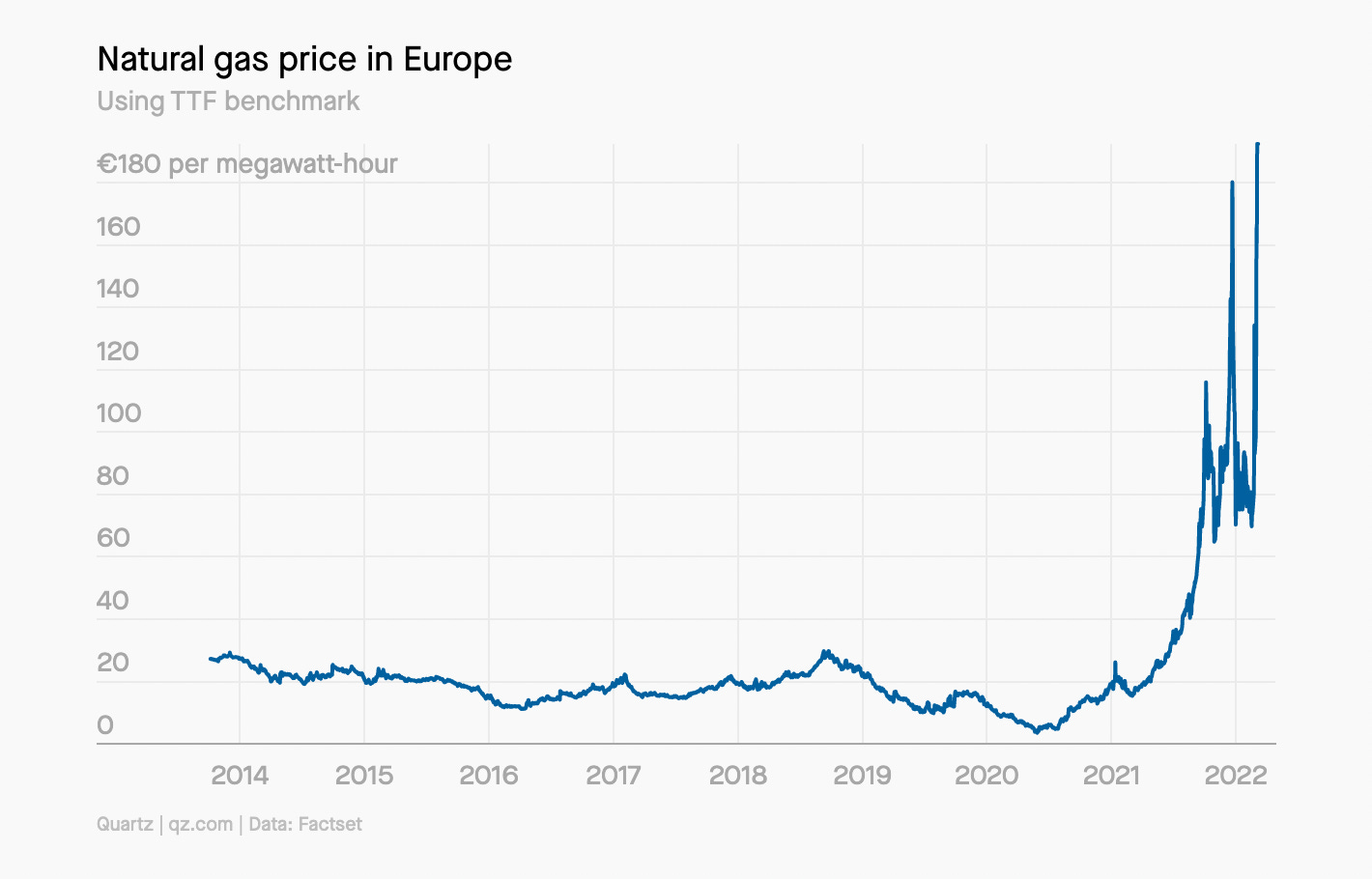

Those pressures pose sharp political challenges, most immediately centred on the costs and difficulties of maintaining our current levels of energy consumption. The price of natural gas hit an all-time high last week, of 345 euros per megawatt hour. This is exceptional: for a decade before the last 12 months, the price had never risen above 12 megawatts per hour. Already, demands from the right are that fracking be restarted in Britain, whilst permits to drill the (rapidly depleting) North Sea fields are to be distributed like confetti; although as Business Secretary Kwasi Kwarteng pointed out, neither will do anything to alter the price of gas as set by international markets. Nor will ditching the Net Zero target, as demanded by Nigel Farage: wind energy is now hugely cheaper than natural gas, per megawatt hour, and British domestic bills are lower over the last year because of wind production (scroll down!).

Source: Quartz

Evidently nonsense in the longer term, the calls to immediately burn more fuel will do little to nothing in the short term, either. But then neither will demands for greater investment in wind and other renewables; it may only take two years to build a wind farm, as Caroline Lucas has argued, but that is two more winters to get through. Labour has doubled down on its demands for green investment but, again, a mass loft insulation programme – essential as it is – does not address most households facing a squeeze right now. The party leadership has dropped its commitment to public ownership of energy production; as its left critics counter, public ownership could be a crucial element in managing disrupted global supplies and rapid decarbonisation. But public ownership would do little for the costs faced by households right now. Programmes for a “Green New Deal” suffer from a similar problem: correctly identifying one of the problems we face in the need to rapidly remove high carbon fuels from our energy systems, they have less to say on the daily grind of rising prices and falling real wages.

Strategy in crisis

There is a difficulty for left political strategy here. It is the same one as presented by the ongoing presence of covid: that there is an urgent need to rethink what we are trying to achieve not so much in terms of a bifurcation between utopia and catastrophe (“socialism or barbarism”, if you like) in which, at some future date, we will collectively either pick the right option, or succumb to civilisational collapse. The point is to understand that we are already living through something like the collapse, and the succession of crises – now including war in Europe – are aspects of that, rather than discrete events. (Adam Tooze has elsewhere referred to a “polycrisis”, which is quite neat but perhaps understates the extent to which the whole is greater than the sum of its crisis-ridden parts.) The point for strategy, then, is not to offer the passengers of our sinking ship a marvellous drawing of the lifeboat we would like have; it’s to find whatever bits of wood or rope are to hand, and lash together a liferaft.

It’s on this point that, in the debate between Green New Dealer Chris Saltmarsh and some of the contributors to a recent volume on “Deep Adaptation”, I find myself in some sympathy with the Deep Adapters – although their specific criticisms are a bit overcooked. But if their demand is to do something now, and to take action without reference to the structures of political parties and government institutions, and the slow pace of change attached to both, then they have a point. Where the Deep Adapters err is in psychologising that demand – shifting it from the political and economic and into the personal, suggesting that the change in our mentality apparently needed to cope with the decaying environment should be our starting point for productive action. This perspective, or something like it, helped frame the politics of the first iteration of Extinction Rebellion, and both gave it a distinctive urgency in its rhetoric and programme – but also very clearly limited its political appeal after the initial shock, as some of those involved in XR recognise.

But then why should we change our mentality? The basic appeal of socialism and the labour movement historically was always its fusion of self-interest with the collective: of recognising that it was possible to achieve more collectively – whether in higher wages or, ultimately, the organisation of the whole economy – than it was as an individual. This has become a harder argument to make in the last few decades, as the “traditional” working class was fragmented and its traditional organisations left far weaker. Yet it still retains its fundamental force: that there is a rational self-interest in demanding more, and that this applies especially in conditions where to demand more means necessarily taking from others. To win more in conditions where you have to take more means you have to be stronger than whoever you are taking from. And for most people, in most circumstances, that has to involve some form of organisation – some collective bigger than themselves.

But for much of capitalism’s history, certainly for the last 80 years or so in Britain, this zero sum logic hasn’t applied. Growth has been high enough that, under most circumstances, it was possible to make one person better off without making another person worse off – Boris Johnson’s infamous “Pareto improvements”. With a reasonable level of growth, capitalism can both deliver rising living standards for most, and still ensure a relatively high rate of return to the owners of capital. The system can function despite – some would argue because of – the demands being placed on it. For as long as growth is somewhere above zero, a programme of reform makes sense. It is always possible for most people to forego something today and still reasonably expect more in the future. Saving for the future makes sense. State-led development makes sense. Social democratic reformism makes sense.

As soon as growth is tenuous or even nonexistent, the logic shifts: losing something today is likely to mean a permanent loss. There will be no guarantee of any losses suffered today reappearing in the future unless they are extracted from elsewhere.

Competition and growth

And – crucially – capitalism does not need growth to continue. Nor does it necessarily produce growth. At the level of the whole economy, there is no guarantee capitalism will grow, but nor is there any requirement it will end without growth. The drive for growth is driven by competition from below: between different units of capital, typically organised as competing firms, sometimes organised as firms in conjunction with states, and sometimes organised directly as states. Competition between them, typically organised through markets, conditions each unit of capital to accumulate more capital: to invest, to produce a return to that investment, and then to push some of that return back into the process as more investment. Do this successfully over time, and the result is not only the growth of individual capitals, but the growth of the entire economy.

But the conditions where this spontaneous market-ordered growth is achievable are themselves contingent. The achievement by any given capital of its own growth does not necessarily mean the system as a whole is going to grow: a firm may have bought a competitor, for instance, or be using its political connections to earn super-profits. However, for a clear historical period, roughly the end of nineteenth century to the early part of the twenty-first, the structures of the system and their relationship to human labour and the natural environment created the conditions where growth could be broad-based and sustained. The rapid but violent, erratic, and narrow growth of the early years of the Industrial Revolution (themselves built on two centuries of more modest growth) gave way to a pattern of capital accumulation where every industry – even including agriculture – could be brought into a higher but, crucially, sustained rate of economic growth that was far in excess of anything seen previously in human history.

That, with the ending of the “Engels’ Pause” in Britain in the mid-nineteenth century, created the conditions in which increases in living standards for the majority could be sustained in the core countries of the West, particularly after the Second World War. The decade after the 1998 East Asian financial crisis saw higher rates of growth outside of the core economies, although typically combined with rapidly rising inequality. After the 2008 crash, growth slowed to a crawl in the core, but continued rapidly outside – right through to the covid outbreak.

This experience of growth is all relatively recent, and, in terms of human history, extremely unusual. It is unclear to me why we should expect the historically highly contingent set of circumstances that enabled sustained growth – a stable natural environment, cheap material inputs, and growth-biased technological innovations that created the conditions for further growth-biased technological innovations – to continue indefinitely. The first two are clearly coming to an end, and the continuing existence of the last condition at least looks open to question. There isn’t some shuffling or reshuffling of the various political and economic institutions that we can make that will change those material fundamentals. It is better to now think of the world as having once had growth, but, in the sustained and life-improving way it once happened, that it will no longer have growth.

The last point – life-improving growth – is particularly important here. It’s not just that growth as such, in the way we usually measure it – the net production of exchange-values, or an approximation to them, summarised in Gross Domestic Product – may look shaky. It is also that, even where such growth exists, capitalism is not reliably producing the broad-based, sustained increases in living standards in its historic core economies. GDP growth there has become detached from improvements in living standards.

Technological catch-up and exhaustion

This doesn’t rule significant potential for catch-up growth elsewhere. The spread of the existing mass consumption products that we have clearly creates this potential: the explosion in car ownership in China in the last decade or so, for example, has helped create a version of the kind of self-sustaining growth, balancing mass consumption and mass production on the basis of rising incomes, that is familiar from preceding century.

We can speculate about how far this can be repeated with future technologies. (Robert Gordon offers one version of this argument, heavily focused on the specific characteristics of the technologies available to us, or likely to become available.) But what we do know is that simply reproducing the existing consumer technology set, with the existing production technologies and their demands for raw materials will merely add to the first two world-historic barriers to growth: the ending of environmental stability and the loss of cheap raw materials.

It’s not necessary to claim future technologies will not produce growth to the extent we have seen in the past; we need only to note that these future technologies will have to work far harder – be far more productive – than those in the past to overcome the rising cost barriers of environmental instability, from covid to extreme weather, and raw material exhaustion.

Zero sum

But if life-improving growth looks difficult, other forms of growth remain open. Instead of technology becoming more productive, people can work harder and be paid less. Terms of trade can be skewed, debt-bondage enforced, technologies and data stolen and, ultimately, wars can be fought for control of resources and people. All of this has formed part of capitalism’s history, from “primitive accumulation” to today. But where once the violence of the system could be pushed into its peripheries, and where technological change created the genuine possibility of broad-based improvements to people’s lives – perhaps reaching their greatest extent in the 2000s – this combination, jointly responsible for the creation and stabilisation of a developed, high-income “core” of the system, appears to be breaking down.

The geographical expansion of the effective core, as many millions moved into a global, mass consumption society, and the continued growth of this core, no longer look guaranteed. In place of this expansion and deepening, rapid technological change is contributing little to material welfare improvements, whilst the essentials of life become harder to obtain, and the systemic violence once pushed to the periphery of the world system moves closer to its historic centre.

The killer, in low-growth capitalism, is that whilst the system as a whole may find growth harder to produce than in the past, the institutional structures of the system still demand growth. The expectation is that investment will still produce a return and that profits will be made. This is the mechanism of competition, red in tooth and claw, that gives capitalism its dynamic: for a period, with favourable environmental and technological conditions, and with the effective organisation of economic institutions – a globally stable money system, nationally organised “productivity coalitions” or, failing that, effective financialisation, say – this could produce the life-improving growth we have identified. Deprived of that possibility, but with the accumulation of capital still demanded, from the expectation of continued growth hard-wired into developed countries’ political systems, and the incessant demand for profits built-in to its business organisation, the capitalism turns into a zero sum game: for me to gain, you have to lose.

Broad-based growth removes this constraint. Growth makes the pie bigger, and so it matters less what fraction everyone gets of the pie – since the pie is bigger, everybody, in principle, can benefit. But without growth, disputes over the size of the fraction matter more and more: horizontally, between competing firms and (ominously) competing nation-states or blocs of states; vertically, by capital against alternative demands for shares of the pie, primarily those of labour – either in the form of wages or, for developed countries in particular, the “social wage” of welfare spending in various forms. And, as Thomas Piketty’s work exhaustively shows, in conditions of low growth it is better to hold a claim to wealth, and extract a growing share of the pie, than it is to try and offer your labour for sale.

For the developed world, we can presumably expect some flourishes of growth, not least after or as a result of preceding crises – witness the covid rebound – but sustained economic growth, running in to the future, of the pace and intensity we have seen over the last 150 years or so appears unlikely. More generally, the presence of low growth increases the relative returns from various forms of rent-seeking and political patronage: it becomes much easier to seek political preferment or monopoly power than it does to try and invest more obviously productive (but increasingly risky) activities. If you want to make money, is it easier to be friends with Matt Hancock, or to build a quantum computer?

Of course, the state can substitute for this lack of entrepreneurial ambition, supplying finance, driving through investment, and creating new markets for products, and the major states (or groups of states) are increasingly attempting to emulate perceived successes like China in this respect. But, again, the presence of greater instability and rising costs means productivity improvements have to be larger and larger to overcome them and produce sustained growth. More likely, over time, is that states themselves will turn to various kinds of globally unproductive rent-seeking and resource-grabbing, playing in to the wider logic of the zero sum game. This includes military competition.

Zero growth capitalism is the war of all against all. But even low growth capitalism can look ugly. Deprived of economic growth, all of us are forced into a mercenary logic: to avoid a loss, for most people, means a necessary loss to someone else, elsewhere in the system. In these circumstances, politics is reduced to a crude injunction: who will pay? becomes the central economic question in a world beset by crises, shortages, and war.

The correct, moral, way through this to pose the issue as an elementary one of justice, in Robin Hood fashion: of taking from the rich to give to everyone else: income most obviously, but also wealth, and creating collective forms of ownership over productive assets. Trade union pay demands are the most fundamental version of this redistribution, but so, too, is the demand to increase the minimum wage. In both cases, the aim is to raise the price of labour faster than the growth in prices, and to squeeze profits to get there. Likewise for demands to tax those making windfall profits, and for caps on the prices of essential goods, like gas for heating. These are all versions of the zero sum game in action. This is where the mass base for a movement can be found.

Beyond that, the requirement is to tie these demands for redistribution into the restructuring of the economy around resource-minimising consumption: reduced working time, more public holidays, more social spaces, more provision of care and education, more digital consumption – all still resource costs, but all of them more efficient than high material use alternatives. (It is interesting to hear, anecdotally, that reductions in working time are becoming more common in collective bargaining, for example.) And the most distant from the day-to-day requirements are the investments needed to decarbonise: essential for the longer-term, but only one component of the whole programme. The core of a left strategy today – including its programme for the environment – is redistribution.

Source > Pandemic Capitalism

The Anti*Capitalist Resistance Editorial Board may not always agree with all of the content we repost but feel it is important to give left voices a platform and develop a space for comradely debate and disagreement.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War