The flag on sale in the local Chinese-run multi-mart is for La Réunion, with the number 974 displayed in the red triangle. There should be a point in the number, for this island is a French département, sending representatives to the mainland from around 900,000 inhabitants, and it is at the bottom of the list with the other overseas territories. It is not even marked with a full number; it is just the number 97.4.

Colonialism

There is a history of struggle here, against colonialism and the forms of sexism that link racism with capital accumulation, and also a vibrant radical history. Activists who built anti-apartheid movements against the South African regime, a regime that the local politicians were willing to back, are still around, some standing for the far-left in the recent elections. Support for the left is difficult to harness, however, either to elections or to popular struggle. Many local votes for Jean-Luc Mélenchon in the first round then went to Marine Le Pen in the run-off with Emmanuel Macron.

There are strong institutional connections to France and attempts to resist that. During the May 1968 events, travel from the mainland was temporarily stopped altogether, but many of the images of what was happening in Europe were of the inexplicable chaos there. It was and still is localised action that counts, action that addresses immediate exploitation and oppression.

Recent protests Fifty years later, in 2018, gilet jaunes protests were massive in La Réunion, bringing the island to a standstill. The movement was quickly bought off, with leaders of the movement being given jobs and housing. The movement is still alive and well, though those involved no longer refer to themselves as gilets jaunes.

Ears

When we arrive at the ‘Qj des zazalé’ old gilets jaunes encampment in Le Tampon in the ‘sud sauvage’, the wild south of the island, accompanied by a long-standing militant and local candidate in the recent elections, we are met with friendly banter that marks us as ‘zoreilles’, old whites from La France.

Why ‘zoreilles’? Possibly from ‘les oreilles’, and that may be because you have to be careful what to say in front of the whites, or it may be because the whites arriving from mainland France had red ears from the sun and stood out to the locals, or it may be that they cupped their ears while getting the incomprehensible locals to repeat what they were saying.

At the same time, whites are still very much in command, and class politics is refracted through racial domination and anti-racism. Those who travel from mainland France, the zoreilles, are given additional salaries, with the ‘correction’ adding a sizeable amount as well as tax concessions which enable them to buy houses, sometimes two or three extra houses, which can then be leased to the locals. This is settler colonialism in practice.

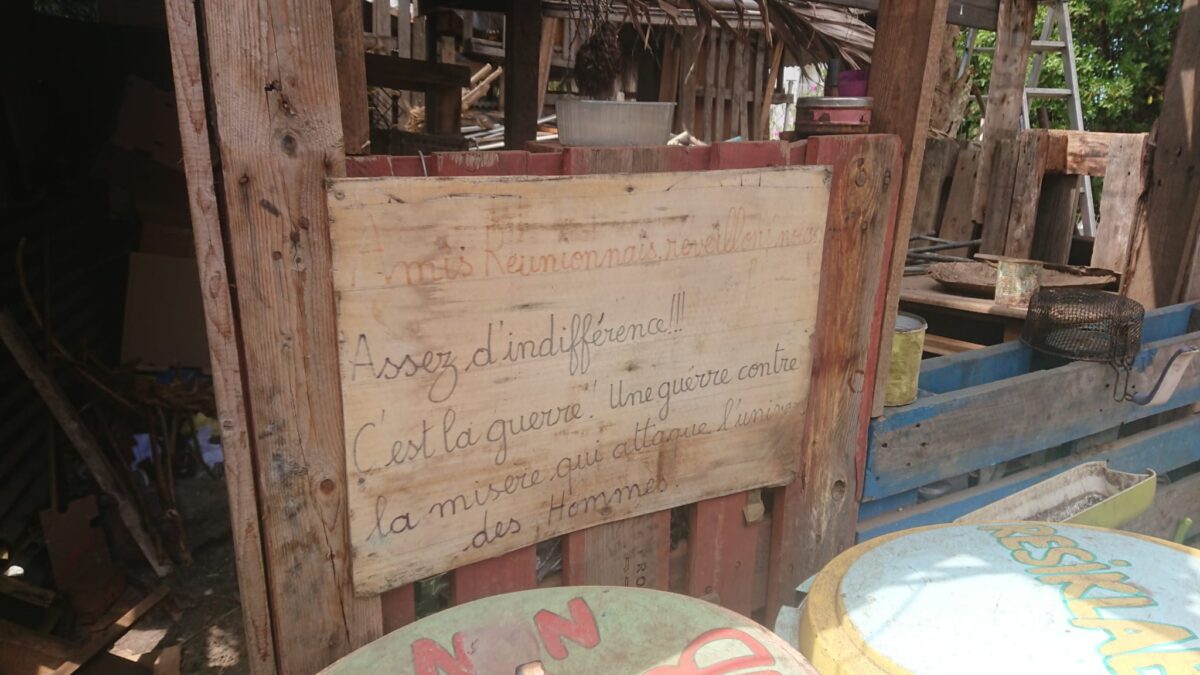

The ‘Qj des zazalé’ camp (General Headquarters of the Azaleas camp) was attacked by the police two weeks ago and has had to be rebuilt after the cyclone. Land nearby in a ravine that was used to grow food has been seized by the authorities. They are under pressure, but a small group keeps the place going, which includes a garden area, “guest quarters”—that is, a small hut—and a café. There are open meetings every Monday to which everyone in the local community is welcome.

These are the remains of the gilets jaunes, and the radicals involved have taken on a new autonomous movement form. Many of the old activists, those who were not bought off, got caught up in anti-vaxx conspiracy stuff during the pandemic, and there are still posters on the walls in nearby Saint Joseph for a mobilisation against the authorities wishing to impose on their right to refuse vaccination passports. The poster carries two flags, those of France and of La Réunion, a sign that this movement is now run by the far right.

Here, as on the mainland, the left has had to be careful around this because these documents pose a real threat to civil liberties. During the pandemic, there were a lot of conspiracy theories, and people didn’t know if deaths were caused by COVID or by dengue, which was a real threat.

Kids

If ‘zoreilles’ are the privileged, and the term used as an insult, if sometimes affectionately so, the ‘kafs’ are those most subject to exploitation and oppression, with ‘kaf’ a racist term that is also designed to infantilise those who are black. A child might also be referred to as a ‘kaf’.

There are local organisations that reclaim the term, one of which, ‘Association Rasine Kaf’, was set up with the help of local comrades building a section of the Fourth International in the 1970s. Comrades then hoped for the island to be another Cuba, allying with Mauritius and Madagascar. Today, anti-racist activists tend to move away from Marxism and only talk about slavery and the fight against colonialism.

There is a focus in these movements on racism and on the interiorisation of colonialism, the way that it becomes embedded in everyday relationships, and that is also a necessary response to the way that French colonialism has operated here. Slavery may have been formally abolished in 1848, but it took many years for it to be effectively put an end to.

Some local cultural practices of ‘maloya’ music, for example, were prohibited until 1981 with the election of François Mitterand. A maloya event was broken up by the police on the day of the election and took place successfully two weeks later.

Internal colonisation proceeds alongside obvious state control from Europe. There is a mural on a wall in Saint Joseph’s for Raphael Babet, for example. Babet was a deputy from La Réunion to the mainland from 1946 to 1957. One of Babet’s big ideas was to found a white-governed enclave town in the middle of nearby Madagascar, also a French colony at the time. The town was founded and named ‘Sakay’, later ‘Babetville’, with La Réunion as a local staging post for the colonial administration. “Colonialism” replicates itself inside each of the colonial possessions.

Power

The local press systematically misrepresents what is happening on the ground. The right-wing daily newspaper Le Journal d’île de La Réunion carries a scare story today over the front page and the first two inside pages about the dangers of prostitution. The centre-left Le Quotidien de la Réunion et de L’Océan Indien fills these three pages of its issue with photos and reports of the run-up to the 11 November celebrations of the end of the war, the First World War.

There used to be a lot of the French Communist Party (PCF) and other far-left groups here. But after Mitterand won the election in 1981, the PCF changed its focus from fighting and being independent to working with other groups and trying to move up and forward within the existing institutions. The field of struggle was abandoned by the PCF, and one result was a lingering hostility among the social movements towards political parties, a suspicion that was present in the gilets jaunes protests. Leftists were welcome, but as individuals, not as representatives of organisations.

Before Macron abolished the wealth tax, the disparity between rich and poor was more visible, with the highest proportion of high taxpayers to those living below the poverty line – now running at 40% – of any other French département. Réunion also scores the highest in whisky consumption. The island imports pretty much everything and exports very little, except some sugar cane. Lifting the wealth tax was a win-win for the super-rich here, whether they are white or not. They kept their privilege, and it was hidden from the official figures. Power is sometimes very obvious here, but the material conditions that make power possible are often hidden. As a concept, poverty is used to put current struggles in context and connect different progressive moments. Everywhere is a function of class position, and the left has a hard struggle ahead to reorganise.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War

Correction: the local communist party was not a branch of the French Communist Party, PCF, but was Réunionaise and was a mass party that fought for independence (against the PCF) and so the shift to the right during the 1970s, formalised in 1981 with election of Mitterand (when it concluded that independence was unnecessary because it could fight inside the system) was all the more dramatic (and it finally lost all electoral influence in 2012).