Mauritius is an African country, but Hinduism is the most widely followed religion. One of the legacies of enforced travel to the island is indentured labour, – debt bondage, with the promise of release after the cost of travel has been paid back, usually a scam. The arrival of indentured labourers is commemorated each year on 2 November. Creole, Kreol Morisien, is most widely spoken, but signs at the airport upon arrival are in English, French, Hindi, and Chinese.

Arab traders knew of it, and then the Portuguese and then the Dutch had their fingers all over the island before the French moved in. The Brits ran Mauritius as a plantation economy from 1810, when they took it from the French, until independence in 1968.

Mauritius is often touted as a successful capitalist economy after independence (and a counterweight to the horror stories sold to Réunion about what would happen to them if they broke from France). It is about the same size as that island to the west—actually a bit smaller with a larger population, despite what taxi drivers tell you. They insist, indignantly, that their island is much larger than Réunion.

Unemployment now runs at about 8%. A B&B host complained that Réunionese on unemployment benefits (with unemployment over there at over 40%) come to cheaper Mauritius on the 45-minute flight east to holiday here.

Race

A strong work ethic, tuned in now to contemporary neoliberalism, is seen as the way out of poverty by many of the dominant Hindu population, and so racial divisions function to divide and rule, as well as to often marginalise Afro-Mauritians. They are part of the “general population,” which is one of the four official categories used to balance representation in parliament, the Assembly; the three specific designated groups are Hindus, Muslims, and Sino-Mauritians.

Gandhi stopped in Mauritius in 1901 on his way to South Africa, and he sent an envoy back to represent Indo-Mauritians in court, where they were still battling over their indentured status. Our Hindu host in one place said her family had been here for five generations, lured here by the British with the promise of gold, but she was glad she was here; she was not Indian, she said, but Mauritian. It was then clear, as she spoke about her neighbours, that lines of heritage among different Indo-Mauritian groups—Marathi, Telugu, and so on—were keenly felt.

At dinner, the host and visitors traded stereotypes, which was followed by a warning: it is fine to say such things in private, but if you post anything negative about another group on social media, you will be visited by the police. During a minor robbery here in the centre of the countryside one night – three youth were caught by a German tourist running off with some electrical equipment. The B&B host, a Hindu, asked if the miscreants were African (they were not).

Some Afro-Mauritians turn to Rastafarianism. Dope was criminalised here, though there is still widespread use. In 1999, there was a crackdown that resulted in mass arrests and the death in custody of Joseph Reginald Topize (Kaya), a well-known local musician and one of the founders of Seggae, a fusion of Reggae and Sega music. One of his concerts was followed by arrests and imprisonment, and he claims that he suffered a concussion after banging his head against jail bars during his withdrawal from drugs. There were riots, and some claimed that this was yet another example of the exclusion and pathologizing of Afro youth.

We were told that there are no Jews in Mauritius, but there is a Jewish cemetery in Saint Martin. The British diverted a ship carrying refugees from Nazi Germany during the Second World War to Mauritius, and Jews were then contained here, dying here or leaving as soon as they could after the war.

Sugar

There were no indigenous people here on the island prior to colonisation. Slaves were transported from Madagascar and then augmented by the import of more slaves and then indentured labour from the Indian subcontinent. Sugarcane was developed as the main crop. Chinese labourers were also brought across, the descendants of whom are now part of the “Sino-Mauritian” community.

40% of the land is agricultural, with 90% of that still taken up with sugar cane plantations, but that is much less than in the old colonial days, and the government is keen to move into finance, in which India is a key player. Mauritius is the main provider of foreign direct investment (FDI) to India through the so-called “Mauritius Route.” India is the second-largest FDI provider to Mauritus, after the US (then it is the UK, Cayman Islands, and Hong Kong). Most of this investment now goes into tourism. Most real estate investment, including hotel complexes, comes from France, South Africa, and the United Arab Emirates.

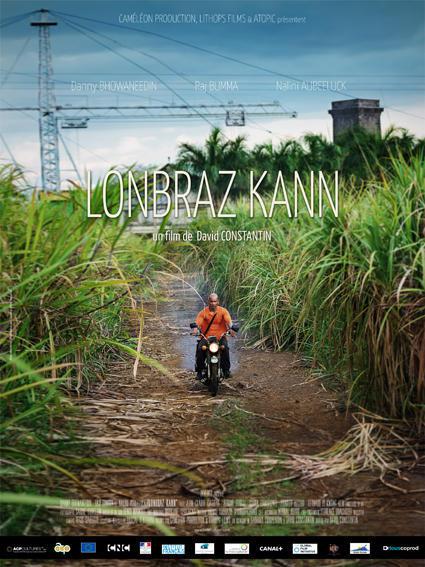

The decline of the sugar industry and the interplay of different racial stereotypes, including those of Chinese as shopkeepers and docile manual labourers, are well evoked in the 2014 film Lonbraz Kann. The title of the film is in Kreol Morisien. You can get an idea of how Kreol transforms the language of the colonialists to find a voice for the people if you say the title of the film and then the title in French, “A l’ombre de la canne” (or, in English, “In the Shadow of the Sugar Cane”).

Gender

There is an active local feminist movement and also a backlash here from men who throw the phrase “cultural Marxism” around (and the unspeakably reactionary British Home Secretary Suella Braverman, known for repeating this far-right phrase, is the daughter of a Mauritian mother who herself was a Tory councillor and parliamentary candidate in north London). So, resistance and reaction of different kinds abound here, along with ideological confusion and internalised oppression. Feminism is present in politics and culture, with some writings by feminists initially banned.

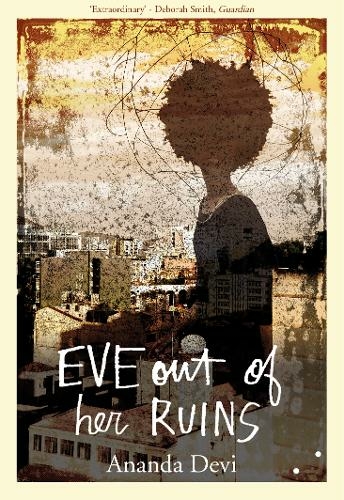

Ananda Devi’s 2014 novel Eve Out of Her Ruins is a case in point, and it captures something of this context for women and the way their lives operate at the intersection with other forms of oppression. The book, originally published in French and then made into a film before it was translated into English, is set in a deprived part of the capital, Port Louis. The fictional name of the neighbourhood is Troumaron, which both Kreol and French speakers will understand to mean “shithole.”

In the course of the story, the four teenage characters encounter sexism, racism, and poverty. There are passing references to Johnny Hallyday, a white South African anti-apartheid rock singer who played at a solidarity concert here before the fall of the regime, to conflicts between Hindu and Muslim youth, and to the scapegoating of Afro youth by the police. The core of the story, however, is the plight of Eve and her relationship with her lover Savita, as well as her sexual exploitation by a schoolteacher. Desperation and power drive the young women, and the young men are torn between violence and solidarity.

Class

The second-largest political party in the National Assembly is the Mauritian Militant Movement, or MMM, which is now an affiliate of the (Second) Socialist International. There is a Hindu-dominated “Labour Party,” also a Socialist International affiliate, and a local party representing Rodrigues Island that is fighting for autonomy. The largest party is the misnamed Militant Socialist Movement, a breakaway from the MMM that governs in an electoral alliance with Rodrigues Island representatives and the Muvman Liberator, another MMM breakaway following a disagreement over MMM support for a Labour Party Prime Minister.

There is also a far-left local party, Lalit, which split from the Mauritian Militant Movement in 1981 and defines itself as feminist as well as environmentalist and internationalist. Lalit, “struggle” in Kreol Morisien, campaigns against the presence of British and US military forces on Diego Garcia, land that is historically part of Mauritius. Ecology is also a key issue here, with the fate of the dodo, native to the island, seen as emblematic. Other species are set to go the same way.

Bats with a wing span of up to 31 inches, Flying Foxes, are endemic, but deforestation has driven them from rural areas into the cities. They can be seen swooping down at dusk to eat lychees and mangos in gardens. Viewed as a pest by many people, they have been wiped out in Réunion, and are now under threat here. Macaque monkeys, introduced by the Dutch, roam wild in some parts of the island and are then harvested, contained, and exported; Mauritius is the biggest exporter of monkeys for research, and the rate now is over 10,000 a year.

Lalit has not taken bad positions on most international questions, and activists have worked in the past with Fourth International comrades in nearby La Réunion (and I saw a copy of a Kreol translation of a book by Ernest Mandel published in Port Louis). There is also a smaller ecosocialist breakaway group called Rezistans ek Alternativ that has been in active contact with the Fourth International in the last few years. A former government minister from the MMM told me that they were still in friendly contact with Lalit and Rezistans ek Alternativ. This is a small place, with about 1.3 million people in total, and in radical political circles, people know each other well.

Current Rezitans ek Alternativ mobilisations have been around the case of Bruneau Laurette, arrested for drug-dealing. There have been protests and a strong police presence against demonstrators outside the court in Moka, just south of Port Louis. This is a difficult test case for civil liberties connected with environmental concerns. Laurette emerged as a problematic populist leader following the Wakashio oil spill off the south coast in July 2020. He raised questions about the failure to clean up after the tanker burst open on a coral reef and about corruption. There were significant demonstrations with an ecosocialist dynamic.

Capital accumulation in Mauritius is no longer directly colonial, but the ruling class is busy investing the fruits of the labour of others overseas, with the finance sector effectively operating as a site of money-laundering. The future of an opposition movement is intimately linked to what is happening in the region and internationally. Much of the left is caught in electoral politics, but there are repeated attempts to break out of that, and as activists do so, they are linking different forms of resistance to envisage a real alternative to the form capitalism has taken here.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War

Correction: police murdered Kaya, and then claimed he was concussed after banging his head. Ix

Correction, sorry sorry music fans, it was Johnny Clegg not Johnny Hallyday, doh.