Hwang Dong-hyuk’s Squid Game (2021)is now Netflix’s most watched series ever. It is not the first South Korean entertainment piece to capture the world’s imagination by highlighting social injustice, following four-time Academy Award winner Parasite (2019) by Bong Joon-ho. There is an appetite for anticapitalist allegory, featuring hells orchestrated not by big brother totalitarianisms, but the whims of the wealthy over a dispossessed, dehumanised and desperate multitude. (Think Bezos and Musk on thrill-trips to space as the world burns below.) In Squid Game debtors are encouraged into deadly children’s contests, overseen by tiers of masked uniforms sporting symbols on their faces: managers (squares), soldiers (triangles), and workers (circles).

There are echoes of the British avant-garde series The Prisoner (1967-68) as eccentrics get transported by a knockout gas to a psychedelic prison controlled by shadowy interests where they are assigned numbers, ‘We don’t use our names in this place.’ (The central villain-player’s number, amusingly, is 101.) But a violent, gamified microcosm of social strife deployed as allegory invites stronger comparisons with Koushun Takami’s Battle Royale; he depicted random high-school pupils fighting each other under the orders of a future Japanese government. Takami’s antecedent, William Golding’s Lord of the Flies, comes to mind too; that was about English schoolboys descending into pagan barbarism after getting stranded on an island. However, Takami and Golding shared a different angle than Hwang; they were criticising children’s upbringings in the Japan and England of their day.

It is Suzanne Collins’s Hunger Games (2008-10) that has the most in common with Hwang’s satire. Crucially, both Collins’s YA novels (and its film adaptations) as well as this 2021 series depict a bread and circuses capitalism wherein the dynamics of control and resistance are enmeshed. (Channel hopping between reality TV and Iraq War coverage gave Collins’s inspiration for her franchise about adolescents forced to battle for a dystopian elite’s entertainment.) Theorist Mark Fisher wrote extensively on Hunger Games, seeing in it a commentary on solidarity.

Hunger Games’ arena, in which the exploited are forced to compete with each other for the entertainment of a bored elite, is as horribly compelling an image of the privation of solidarity in our world as you could wish for. Any alliance in the Hunger Games’ arena is necessarily provisional – since (in the ordinary course of things) there can only be one winner, every member of an alliance knows that they may well face the prospect of eventually having to kill those with whom they are now temporarily allied. The struggle to break out of the arena entails the throwing off of this imposed Hobbesianism, the (re)invention of solidarity.

Mark Fisher

In Hunger Games solidarity is urged by the adage, ‘Remember who the enemy is.’ While oppressed individuals are frequently divided, they can exercise unity to end that condition, fighting oppressors. In Squid Game, the basis of solidarity is framed with an almost Brechtian lack of sentimentality: ‘Listen, you don’t trust people in here because you can. You do it because you don’t have anybody else.’ Oppressed and exploited people have plenty to fear in one another. Living in prejudiced and competitive societies, they are more likely to clash with those on the same rung. But solidarity can be a necessity.

At one point in the show a game requires teams of players to operate together. Already small acts of solidarity, kindness or even (quite Hobbesian) enlightened self-interest have seen characters survive, but now it is only through the formation of a strategic, organised solidarity (in short, camaraderie) that they will persevere. The games that divide, unite. As Marx and Engels’s put it, ‘What the bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave-diggers.’ Hwang is attentive to contradiction, but also to perversity; the games that unite, cruelly divide, as later episodes show. Capitalism does both as well, as Marx showed.

As with Hunger Games, Squid Game is about the privation of solidarity. Its insights are oddly perhaps best examined through the critical theory of postwar America. In Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer’s theory of the Culture Industry, mass media culture by its nature is argued to render its audience passive about their material conditions. (Unable to unite to overturn class society.) This result is achieved not by conspiracy, but because popular culture’s requirements, a broad appeal, means that it produces both high culture’s intellectual fulfilments while still satisfying the basic urges embodied in low art. It confuses the divide between critical awareness and unthinking consumption, satiating drives that could find release in resistance.

Squid Game tackles what theorist Richard Seymour calls the Social Industry and the A*CR’s Neil Faulkner, building on Guy Debord, calls The Wall (a web 2.0 version of Adorno and Horkheimer’s diagnosis, manifested in billions of screens). Here, mass culture’s appeal is married to passive participation, with the medium manipulating an audience’s interaction to mimic freedom, creating something more effective than a postwar Culture Industry. When you log on social media, circumstances (algorithms) gently induce behaviour (on Twitter and Facebook: superficiality, competition, paranoia). Likewise, a platform like Netflix persuades you that your docile past viewing dynamically shapes future viewing, that it appreciates your individuality, but your agency here is an illusion.

The managers in Squid Game present the illusion of choice, performing an ideal of liberal democracy by strictly enforcing rules or allowing the players to collectively leave. During a vote that takes place in the series, the masks go as far as affecting bourgeois outrage at attempts to ‘subvert’ their ‘free and fair’ elections, ‘We will not condone any act that impedes this democratic process.’ This obscures the artifice, naturalising the games by hiding the economic coercion that allows for them. Hwang is not coy, a character states the situation bluntly, ‘Just as bad out there as it is in here.’ The contrast between ‘out there’ and ‘here’ is false, South Korea’s hyper-stratified, oppressive society is the truest antagonist.

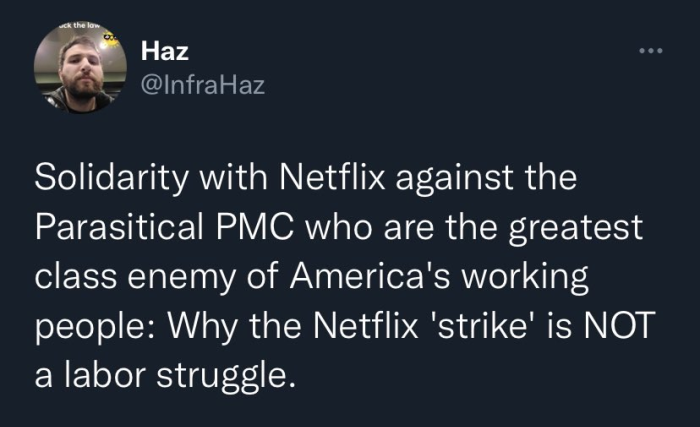

As mentioned, Netflix is a part of the Social Industry, The Wall, and thus what the show satirises. It is a lucrative business exploiting for profit. For example, it often pink washes, assuming the trappings of queer culture in shows like She-Ra (2018-20) or pro-trans documentaries such as Disclosure (2020), while elsewhere playing up anti-queer sentiments. Egregiously, they host homophobic and transphobic content like court comedian Dave Chapelle, whose act includes bemoaning ‘the alphabet people’ (a cheap dig at LGBTQI+ identities). When workers protested, Netflix fires them. If Squid Game concerns the privation of solidarity, what about paying for Netflix? We can be sceptical of consumer activism, but what of alleged ‘socialists’ siding with a multi-billion dollar, tax-dodging company against the oppressed?

Hwang is an effective storyteller. The series’ horror is so chilling partly because of the conceit of using children’s games. Any fan of horror knows the genre often deftly juxtaposes vulnerability and innocence with foreboding threats. Hence so many slasher victims murdered in their beds; doll and clown monsters; demonically possessed girls, etc. The contrast of frivolous kid’s games and slaughter leaves an impression. It is foreshadowed in the titular game, in an opening prelude, and during an early episode when the protagonist wins his daughter an arcade-machine gift, not realising it is a novelty cigarette-lighter handgun. There are many more brilliant touches: aspiration and inter-class resentments; religious escapism; South Korean labour conflicts; the politics of anti-immigration; gender and racial hierarchies; pastiches of liberal equality and meritocracy.

Like every series, Squid Game is a collaborative work involving enormous expenditure on various talents, credited and not. Jung Jae-il (composer for Parasite), with Park Min-ju and Kim Sung-soo’s assistance, create a tense, eerie score. The cast are compelling; Lee Jung-jae stands out as gambling-addicted chancer Seong Gi-hun, a role demanding versatility. Costumes and sets are all spectacular, as bold colour schemes blend with whimsical architecture. (Passageways linking the games are modelled on M. C. Escher’s surrealist stairways.) There is little to take issue in the execution, helping to explain how it touched such a cord.

Squid Game points beyond itself and captures the historic discontent of a capitalism in crisis, but can it wake audiences from passivity, will it reinforce the systems at which it takes aim, or is this just another innocent distraction?

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Protest Review Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Ukraine United States of America War Women

Living on Universal Credit here in the UK, I am not faced with the problem of whether a socialist should subscribe to Netflix or to any of the other capitalist streaming services. I saw Parasite and read it as a contemptuous dismissal of the poor of South Korea, portraying them as greedy, dirty, stupid and self-obsessed. Did I misread it? The Squid Game I doubt I’ll see.

I interpreted Parasite as Brechtian, the ethos of ‘first feed the face, then talk right and wrong.’ (Don’t think I fully agree with Brecht, but it seems the viewpoint of Bong Joon-ho’s movie too). That is, the anger of the story felt to be foremost directed at the rich family, whose ignorance and sadism was incredible (there’s the titular ambiguity about which family is the parasite). But texts (including films) are interpretively open.

Total solidarity. I’ve gone through periods depending on DLA and such, our system of welfare is a cruel, unjust travesty.