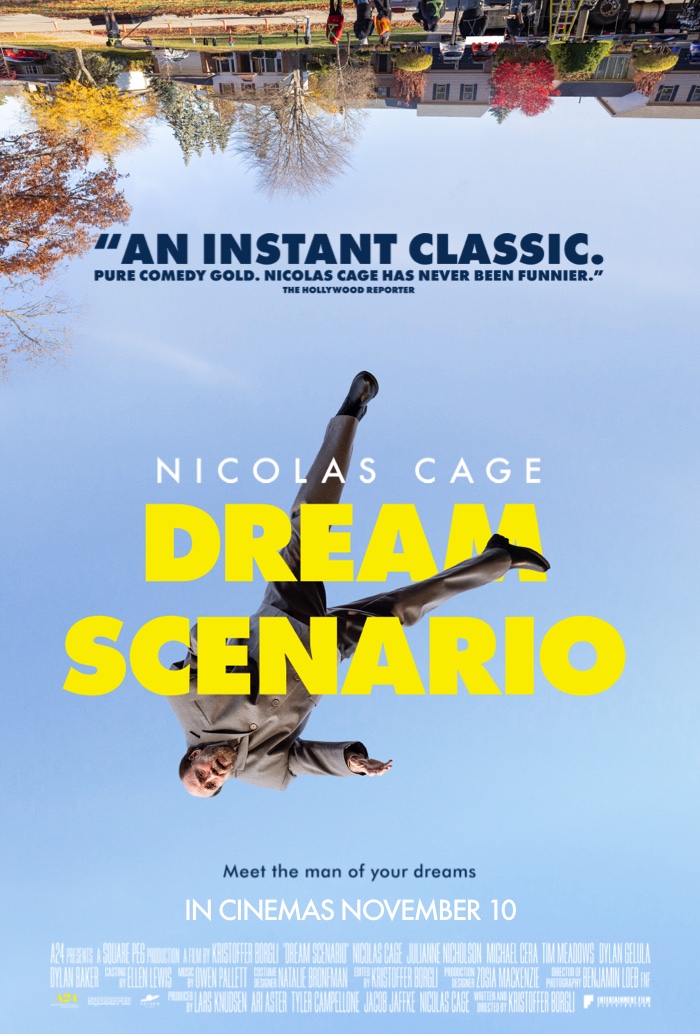

Dream Scenario, released at the end of last year, stars Nicolas Cage as Paul Matthews, a college professor seething with resentment at not being recognised for a book he has not even started writing, and then paying a horrible price for being noticed, more than he would have liked. Paul lumbers around the sets with a goofy expression and an anorak pasted onto his back, and gives fake “inspirational” lectures (the staple of Hollywood films about college professors) about how zebras blend into the herd to stay safe and only stand out in order to mate.

Scenarios

Things start going awry when Cage, who is also producer of the film, starts appearing in people’s dream, not doing much, but as a passive onlooker. It’s creepy. People start to compare notes, and Paul can’t resist seizing this opportunity to break out of dumb anonymity into being a celebrity and, his game-plan, to get a contract for his book on evolutionary biology. An agency takes him on, offering him a deal to promote Sprite in peoples’ dreams, which he objects to, or to appear in Obama’s dream, which he likes the sound of.

Paul Matthews does become a celebrity, but people are frightened, and when he is singled out, he reacts, and when he reacts he is perceived, dreamt of, as being violent, and then he is scapegoated – the celebrity becomes a threat – and feared. Along the way there is a ghastly sex-scene when one dreamer tries to get Paul to enact the experience they had fantasised about with him, and one reviewer remarks that you will want to take a pen-knife to scrape away the memory of the scene (and they are right).

You will watch all this unroll for the first agonising four fifths of the film before the narrative lurches into a daft alternative near-future scenario in which people are able to use new technology to leap into others’ dreams. There are ironic references to the commodification of life, but any progressive reading is wiped away, and you are left with the kind of hopelessness that Paul is wallowing in at the start of the film.

Alienation

There is something intriguing about all this because it taps into something of the formation and experience of subjectivity under capitalism. This is a film about alienation in a number of key aspects. One is the reduction of people to being passive spectators, but that passivity, as we can see in the case of Paul, is laced with anger that cannot be channelled into productive activity. It is incited and blocked. People become ill as a result.

Another aspect is anonymity, the kind of thing that was described in US American sociology as the phenomenon of the “lonely crowd,” in which we are living alongside other people without really relating to them, and that lack of recognition also feeds into a sense of being isolated and helpless. Paul craves recognition for his achievements but cannot do anything to break out of his little prison.

The third aspect of alienation is atomisation, the imprisonment in the sense of “individuality” that is promoted as a vision of autonomy and freedom but which actually divides people from each other. This is where Paul’s passionate lecture, which he is fixated upon – he repeats it during the course of the disastrous date with an admiring dreamer – is so emblematic; zebras blend in to stay safe and stand out to get sex, excitement with others.

These three aspects of alienation are at the heart of the escape attempts that are provoked in us, that we might break out, become active, that we might actually link up with others, gain recognition, and that we might realise ourselves as fully human and – here is a trap – become fully independent.

That third escape attempt, and here in the film it is to become a “celebrity” (like Cage is in real life, in a fake-reflexive twist on the ideological core of the film), and so we become all the more locked into the forms of individuality that are provoked by capitalism and intensified under neoliberalism, locked into our little selves instead of becoming human as part of a constructed collective endeavour.

Dreams

This is where dreams come in, and they are not only explicitly a topic of the film Dream Scenario, but we are offered a “theory”, if you can call it that, for how all this works. In the even more crappy final fifth of the film someone marketing the new technology that allows everyone, and not only Nicolas Cage, to enter other peoples’ dreams, opines that the real lesson of Paul Matthews’ celebrity appearance in dreams is that “dualism” – the split between our bodies and our minds, between material reality and the ideas we have about it, is true. More than that, there are specific “theories” that also turn out to be true. Enter stage right one of the ideological master-keys to dreams and our unconscious fantasies, psychoanalysis.

Dream Scenario peddles not only dualism, an ideology about who we are in the world that divides us from it, but also banalised versions of psychoanalytic theory. First off, and this is voiced quite explicitly by some of the characters to explain how Paul Matthews appears in their dreams, is Jung. Carl Jung, who talked about a “collective unconscious” that was “racial”, and who came out with antisemitic and other racist comments during his time as head of the Nazi-controlled psychotherapy organisation in Germany after Freud and his followers were hounded out, is a go-to for some of the most reactionary ideas about our yearning for individuality, collectivity and change.

Here in “Dream Scenario” Jung’s ideas are wheeled in to not only account for the weird events in the first four fifths of the film but actually to advertise the possibility of telepathically-shared dream worlds (even if there are also some little digs at the way that commercial enterprises might harness that to their own ends).

The other psychoanalytic element is hinted it, and actually ideologically underpins how Paul projects himself into dreams. This element comes from the work of Melanie Klein, one of the most biologically-reductive of present-day psychoanalysts, with a mainly conservative influence, following her death, in psychoanalytic organisations around the world. She argued that through what she called “projective identification” it would be possible for fantasies to be conveyed from one mind to another, most significantly, for her, from the mind of the psychoanalytic patient who would “project” unwanted parts of the self which they continued to identify with. In “countertransference”, the psychoanalyst would pick these up and then, hey presto, some kind of telepathic communication was at work. This daft idea is also, of course, of a piece with dualism, with the independent life of ideas and their circulation outside of material reality.

Some of my psychoanalytic colleagues will tell me that they reach for Jungian and Kleinian ideas in their own work and find them useful. That’s fine, but here in this film we are given an opportunity to notice how those ideas also play out ideologically in popular culture outside the clinic. The real problem is when specific techniques are turned into a complete worldview (and in this case, two complementary psychoanalytic worldviews) that is functional to capitalism.

Real life

So, though Paul Matthews tells us about zebras, and wants to write a book about evolutionary biology, the “explanation” we are sold, under the counter as it were, is a quasi-psychoanalytic one. Dream on. This film might be a critique of alienation, but it offers us no way out, only the fantasy that we might peel off that anorak and turn out to be not Paul Matthews but a famous real-life film producer Nicolas Cage. Avoid it, or, if you are tempted, step back and think critically about what you are being sold in this film, and look to quite different scenarios for combatting alienation, ones that are constructed collectively in our real lives together rather than searching for only fantasied individual ways out.

Art (47) Book Review (102) Books (106) Capitalism (64) China (74) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (43) Economics (36) EcoSocialism (48) Elections (75) Europe (44) Fascism (52) Film (47) Film Review (60) France (66) Gaza (52) Imperialism (95) Israel (103) Italy (42) Keir Starmer (49) Labour Party (108) Long Read (38) Marxism (45) Palestine (133) pandemic (78) Protest (137) Russia (322) Solidarity (123) Statement (44) Trade Unionism (132) Ukraine (324) United States of America (120) War (349)