The picture opposite is the sole surviving work of the painter Mary Grace. However, during her lifetime, she exhibited at the Society of Artists every year from 1762 to 1769 and was elected as an honorary member. Records tell us something about these fifteen paintings. Some were portraits that could be sold in a growing market. There were also several contemporary scenes, such as one of pea pickers cooking their lunch, as well as pictures with literary and classical themes. Grace was already breaking out from the narrowly defined genres that women painters were supposed to address, such as portraiture and flower still lifes. Despite this, her work has all but vanished. This exhibition brilliantly dispels certain myths—that there were very few women painters or that very few exhibited publicly and made any money—but it also explains how and why much of their work has not found its way into art history.

Putting on this show involved a degree of ‘archaeological exploration’ and detective work. Records were not always kept of women artists’ work and sometimes it was misattributed to men. While it became possible for women to paint as a pastime or hobby and distribute their work to relatives or friends for a fee or as gifts, any attempt to set up a commercial business sparked significant societal disapproval. Middle-class women—it was nigh impossible for working-class women to paint—were legally and socially inferior to their husbands. To train as an artist, one needed to observe nude life models, which was considered morally outrageous for women until well into the 19th century. In any case, women were not admitted to art schools before then. This show highlights those early pioneers who began to break through these restrictions.

Kaufman was the exception that proved the rule. Arriving from Europe, where she already had a reputation, this Swiss painter, along with Mary Moser, was one of only two women who formed part of the founding membership of the Royal Academy in 1768. The Academy became the most important arts institution for aspiring artists. But as women, they were excluded from the Academy’s council, committee meetings, and life drawing classes. No other women achieved Academy status until 1936. The picture above is based on a poem by the Gaelic bard Ossian. Imbaca, disguised as a soldier, shocks Trenmor by revealing herself to be a woman. You can imagine it was a rather unsettling image at the time. Often Kaufman’s history or classical paintings reflect the actions of women—their fortitude and virtues. Her depiction of the elements of art for a ceiling in the Academy featured all-female figures. Male artists were defined as the only people able to render the noble sentiments of classical themes or battle scenes. Women were supposed to paint delicate, feminine subjects like flowers or sweet portraits. Kaufman’s work can still be seen today in the Royal Academy in Piccadilly and also at Kenwood House on Hampstead Heath, where it is part of the great permanent free exhibition.

Another noteworthy 18th-century woman artist pioneer was Katherine Read, a Jacobite Scot who had trained in Paris and Rome with Quentin de la Tour. Many women artists who pursued an artistic career benefited from fathers or relatives who were already established artists, such as Artemisia Gentileschi, who has two pictures in this show, painted while at Charles I’ court. Read used her Jacobite connections to travel as an unmarried woman, which was very rare at that time. In letters to her brother, she complained about being in the ‘unlucky sex’ and a ‘Creature in a very odd situation’ (p.53, catalogue). Many of her works were misattributed to men. This picture really struck me when I saw it in the exhibition. Read worked around the sites of the Grand Tour, which aristocratic men would do as part of their ‘education’—think of it as an elitist gap year where they let their hair down too. Here she captures something between the older tutor and his student. The gaze and the entangled, delicate fingers suggest great tenderness or maybe something more. Read ensured the wealth she accumulated up to her death was left to her nieces, believing that women needed financial independence.

Another example of the sole surviving oil painting of an accomplished woman artist is shown here. We see a doctor lost in thought, wearing a crumpled suit and leggings. A learned man, he has a book on his thigh, and his spectacles could fall from his hands at any time. The image exudes reflection and some tiredness—a doctor has to get around a lot. Compared to many stiff, boring portraits displayed in museums and particularly stately homes, this is a more unorthodox, interesting piece of work. Black shows a technical virtuosity equal to the well-known portrait painters of the day. There is a story behind this painting that exposes the difficulties of being a woman painter. Letters between Monsey and his cousin, Mounsey, also sitting for Black, show how they tried to avoid paying her even the half-price rate that she, as a woman painter, demanded. Someone like Joshua Reynolds would charge £50, whereas Black would accept £25. But these two men thought that the opportunity they ‘gave’ this ‘sweet woman’ to paint their pictures was privilege enough. Black quickly tried to placate them by offering to negotiate down to a quarter of Reynolds’ rate or whatever ‘he felt proper’ (p 52 catalogue). Mounsey declared: “Sorry to find Miss Black is grown so saucy, as it will only embarrass or stop the progress of her reputation and improvement.” Monsey even referred to Black as a ‘slut’ in another document. The painting remained in Black’s possession until her death. Looking at the portrait again after hearing the background, you see something else—male entitlement as he sprawls, the comfortable male professional in charge of all he surveys.

In 1857, the artist and activist Barbara Bodichon published the radical pamphlet Women and Work. She wrote:

“Awake, Be the best that God has made you. Do not be contented to be charming and fascinating; be noble, be useful, be wise…Grasp the hand that points to work and freedom.”

(p.113, catalogue)

Emily Osborn, who knew Bodichon, exhibited the painting above at the Royal Academy. You see an orphaned young woman artist offering a painting to a dealer who appears to be on the point of rejecting it. It was difficult even in the 1850s to sell work without a reputation or connections. The two men in the background show their disrespect and contempt while the woman is surrounded and isolated in the centre of the composition. Like a screenshot from a movie, there is a lot going on and you are pulled into the story. Ironically, given its title, the picture sold for £250, which was a very good price.

Claxton, as you can see from the style of the painting above, was mainly a graphic illustrator. In the best traditions of Hogarth or the satirists of Punch magazine, she depicts the situation of women. At the centre, women worship at the feet of a man seated below a statue of the Golden Calf (false idol). Around this, you can see women attempting to make progress in various professions—on the right, you can see a woman who finds the door of the medical profession locked to her. A gap in the wall symbolises emigration as a solution. A woman artist, Rosa Bonheur, is shown climbing a ladder to view the forbidden fruit beyond. The work was slammed in the press for ‘sermonising on social topics’.

There are many other great pictures to discover in the exhibition—Elisabeth Butler’s Roll Call (1859), depicting a military scene from the Crimean War, was a critical and popular success; Henrietta Rae’s sensual nude paintings such as Psyche Before the Throne of Venus (1894); or Lucie Kemp-Welch’s huge, spectacular Colt Hunting in the New Forest (1897). The exhibition finishes with painters notably from the early twentieth century, Laura Knight, Sylvia Gosse, and Gwen John.

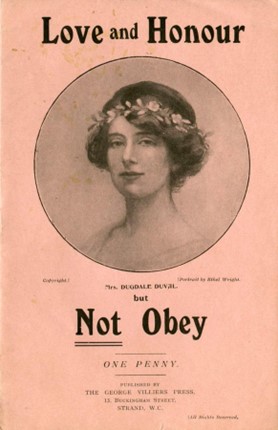

We can end this review with a gorgeous, richly coloured portrait by Ethel Wright (1866-1939) of the suffragette, Dugdale Duval, who notoriously refused to promise to obey her husband during her marriage vows. She had written a pamphlet called Love and Honour but not Obey with a cover illustration painted by Wright. Her portrait utterly destroys the press and establishment propaganda of suffragettes as unattractive harridans. She is presented as cultured, confident, and vibrant.

Pictures taken by Dave Kellaway.

Art (47) Book Review (102) Books (106) Capitalism (64) China (74) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (43) Economics (36) EcoSocialism (48) Elections (75) Europe (44) Fascism (52) Film (47) Film Review (60) France (66) Gaza (52) Imperialism (95) Israel (103) Italy (42) Keir Starmer (49) Labour Party (108) Long Read (38) Marxism (45) Palestine (133) pandemic (78) Protest (137) Russia (322) Solidarity (123) Statement (44) Trade Unionism (132) Ukraine (324) United States of America (120) War (349)

Great review, perceptive comments. Many thanks.