This exhibition at the Tate Modern is the first major London retrospective of Philip Guston’s work. His art was a personal and political response to the wars, racial injustice, violence, and political and social upheavals of the 20th century. Guston is much less known than some of his friends, like Pollock or De Kooning, but this show is a welcome introduction to somebody who stayed on the progressive side of the artistic community. His legacy is considerable, as his later work in particular became a reference point for future generations of artists. Like the best artists, he did not stay fixed in the same style or look; he developed and experimented through his life. As he himself stated:

Probably the only thing one can really learn—the only technique to learn—is the capacity to be able to change.

from the free guide, p. 3

You can see work from the three main phases of his career:

- The socially committed public art of the 1930s and 1940s

- Abstract expressionism of the 1950s

- His turn away from abstraction and towards the figure in a new cartoon style from 1966 to his death in 1980

Like Picasso’s Guernica, this picture tries to portray the horror of the Nazi bombardment of the Basque town carried out in support of Franco’s fascist army. He uses the Renaissance tondo frame and muralist techniques to create this explosion of terror. The shape of the painting mirrors a bomb’s roundness. The conflagration hits us in the eyes in the centre, and the devastation is blasted out to the rim. It makes no attempt to naturalistically show the bombing. The war planes are placed on the side and not at the top. A dominant figure with the gas mask and strong red shirt seems to be coming out of the picture from the top towards the viewer. A naked child lies at the bottom, grasped by a mother whose face we cannot see. We see figures distorted just as they might seem in a maelstrom of an explosion with the rushes of air and reverberations of sound. The overall effect is breathtaking, particularly if you have never seen it before. It is worth the price of entry alone. This picture was made for an exhibition organised in New York for the American League against War and Fascism.

Guston commented on his activism during this period:

I grew up politically in the thirties and was actively involved in militant movements and so on, as a lot of artists were…I think there was a sense of being part of a change or possible change.

Guston joined the Bloc of Painters, formed under Mexican muralist David Siqueiros. The exhibition has a large-scale reproduction of the mural he created with friends Reuben Kadish and Jules Langsner in Morelia, Mexico. Called the Struggle against Terrorism, it shows people’s resistance to persecution and violence from the mediaeval period through the Ku Klux Klan in the US and the rise of fascism in Europe. He had had direct experience with the Klan while living in Los Angeles. New Deal public art projects sponsored his work at the time. Representation of the Klan continued in his pictures, particularly in his third extremely innovative and creative period.

War and the Holocaust deeply affected Guston, who was Jewish, and it led to a certain crisis in his work where he said, ‘I couldn’t continue figuration’. He even destroyed pictures he had made while in Rome on a fellowship. When he returned to New York, he joined the growing scene of abstract painters like his new friend, Mark Rothko. As he explained, he was ‘less concerned with making pictures but only with the process of creation’ (…) ‘I feel that I have not invested so much as revealed, in a coded way, something that already existed.’

If you look at Guston’s abstract pictures of the time, they were never as abstract as, say, a Rothko or Pollock. In this picture, you get a sense of people moving across the picture. The artist, Tacita Dean, comments in the catalogue (page 81) that ‘the agitatedness of his surfaces clearly suggests that there is company concealed there.’ Perhaps it was not a surprise then that Guston was one of the first of the abstract expressionists to move on to a different type of art. Of course, this detour through abstraction meant his new work was going to be quite different from the representation he had developed previously. He started to exclude colour and used shades of black and grey with block-like heads. Guston remarked:

The trouble with recognisable art is that it excludes too much. I want to include more.

He went through another crisis and started to draw some simple line pictures. Then, in his 1970 exhibition, he shocked friends and critics with a sharp change of style away from abstraction. The work looked crude and cartoonish and included odd combinations of everyday objects thrown together. Critics called him out of touch, and some friends even stopped talking to him! I think art critic John Perrault was right when he wrote in the Village Voice at the time:

It’s as if De Chirico went to bed with a hangover and had a Krazy Kat (a cartoon character) dream about America falling apart.

People did not like the way it appeared that he was trivialising or humanising the Klan by putting these hooded figures in everyday situations.

However, by using cartoons’ capacity for satire, the painting challenges projections of strength and intimidation, presenting these figures instead as ridiculous yet unsettlingly commonplace.

from free guide section 8

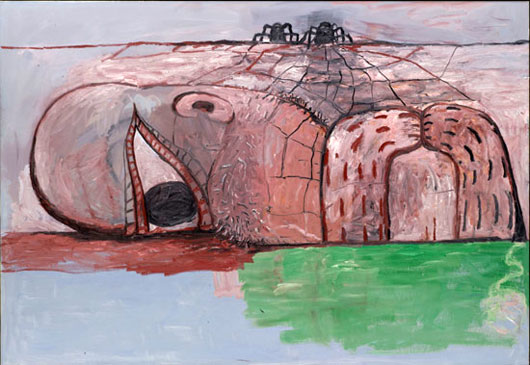

You can be the judge. Here is an example of one of these pictures:

Looking at this picture, you can see the influence on later artists whose pictures look similar. The boundaries between cartoon styles and higher art styles are erased. Guston is also saying something about how the evil of racism is masked in society. He points out how society is complicit in racist acts.

In his last years, he filled his paintings with his memories and personal hardships. He began to represent himself as a sort of giant Cyclops. Piles of rags or boots, twisted legs, and other junk fill up his paintings. Both his poet wife, Mckim, and he himself experienced health problems. He seems to smoke all the time, both in his pictures and during the long, fascinating film you can see at the end of the show. He died young, at 67, and there is a brooding sense of mortality in his later work.

How do we all feel about maybe waking up at 4 a.m.? The images are cartoonish but also nightmarish. It is difficult not to react to a picture like this with the spiders advancing towards you from the horizon at the top. The cloud of redness further intensifies anxiety.

There is tenderness in these later paintings, too.

Here we see Guston sleeping with his wife, his paintbrushes in his hand, a pie ready to eat, and always his big boots. He used to often paint all night, so the brushes were never very far away, and he may well have snacked through the dark hours. Those horrific scenes in the concentration camps with the massive piles of boots may explain why they are so prominent in his work. The final room is full of remarkable paintings; he really did end his career with a great flourish.

Socialists work to build a better world, an alternative to capitalist inequality and the destruction of our planet. We have to be creative and imaginative to work for this in a situation where people have said it is easier to consider the end of the world than the end of capitalism. Artists like Guston do not just fill their pictures with a bit of progressive content; their disruption of artistic conventions and conformity mirrors our need to think outside the box of everyday normality. Any socialism worth fighting for includes a big space for people like Guston who interrogate us about how we can see and understand ourselves and this society.

Guston’s earlier radicalism did not desert him. He was co-chair of CORE (the Congress of Racial Equality) in 1966. He denounced the state violence against the demonstrators at the 1968 Democratic Convention. In that year, he stated the artist’s mission to:

Unnumb oneself to the brutality of the world, which is the only reason to be an artist—to bear witness.

Art (47) Book Review (102) Books (106) Capitalism (64) China (74) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (43) Economics (36) EcoSocialism (48) Elections (75) Europe (44) Fascism (52) Film (47) Film Review (60) France (66) Gaza (52) Imperialism (95) Israel (103) Italy (42) Keir Starmer (49) Labour Party (108) Long Read (38) Marxism (45) Palestine (133) pandemic (78) Protest (137) Russia (322) Solidarity (123) Statement (44) Trade Unionism (132) Ukraine (324) United States of America (120) War (349)

Excellent review Dave and agree about the documentary. I missed the start but watched most of it before going in – for almost an hour – which is unusual for me in such contexts. That helped when I was going through the galleries. Interesting also that the abstract work did not hold my attention for very long but both the early and late work did.

Yes I had never seen his work before. Even the abstract work is beautiful. The film for me confirms that he was one of the good guys.