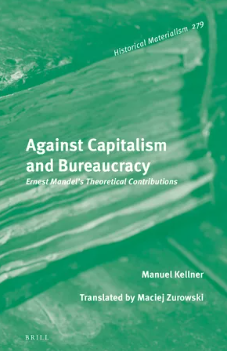

Manuel Kellner, a Fourth Internationalist comrade in Germany, had the good fortune to be able to write his doctoral thesis on the work of the Belgian Trotskyist activist and theoretician Ernest Mandel. Now here it is: Against Capitalism and Bureaucracy: Ernest Mandel’s Theoretical Contributions, published by Brill in the Historical Materialism book series Like Mandel himself, though, this is not the kind of study that reduces politics to an academic seminar piece. Kellner grounds Mandel’s work in practice, as someone embedded in and often leading political struggle.

Politics and economics

The book opens with an illuminating anecdote about the relationship with academic institutions, but to make a political point. In 1972, Mandel was offered a position at the Free University in Berlin but was then blocked from taking up the post by the authorities, who were concerned that appointing a revolutionary Marxist who was explicitly dedicated to taking down the German capitalist state would be a big mistake. The political senate of West Berlin put the problem as follows:

“His aim is the creation of a council republic of a Trotskyist character, led by a national congress of workers’ councils as the highest decision-making body on economic and socio-political issues. In this way, the liberal democratic order set out in our constitution is to be destroyed completely.”

There is a lot to unpack there, but what they claimed was that Mandel would surely use his position to link with student and worker mobilisations. They were right. He would, and the mass protests against the ban on Mandel entering Germany did themselves enable exactly what the authorities feared: the raising of consciousness and the building of left organisations.

Mandel was a respected economist and theorist of what became known as ‘late capitalism”—a societal transformation based on the emergence of new technologies and the rise of the service sector after the Second World War—and “long waves” of economic development that tracked periodic crises of overproduction and attempts by the state apparatuses to ensure that, just as surely as growth leads to profit-taking by the bourgeoisie, the costs of austerity would be shouldered by the working class. But building left organisations was actually at the heart of Mandel’s work. What, indeed, was the point of the most sophisticated “analysis” if it did not enable critique, challenge, and change?

In this sense, Kellner shows us, Mandel was Marxist to the core, concerned always with Marxist “science” as a kind of science that links theory with transformation; what we learn about the nature of capitalism must impel us to take steps to end it, to shift from the individualising of experience under capitalism—the speciality of bourgeois and petit-bourgeois culture—to the collective conscious self-activity of the working class. The left organisations that Mandel dedicated his life to were those in and around the Fourth International, and a good number of key theoretical documents that Mandel prepared were specifically designed for these activists and those they worked with.

“Mandel was a respected economist and theorist of what became known as ‘late capitalism’—a societal transformation based on the emergence of new technologies and the rise of the service sector after the Second World War—and ‘long waves’ of economic development that tracked periodic crises of overproduction and attempts by the state apparatuses to ensure that, just as surely as growth leads to profit-taking by the bourgeoisie, the costs of austerity would be shouldered by the working class.”

Democracy and education

The “liberal democratic order” that the West German state was concerned about when they issued an entry ban on Mandel was, it turned out, not only profoundly undemocratic but, as Mandel argued, designed to protect the class interests of those with immense power. The illusion that opponents of Marxism promoted was not only that they were democrats but that the revolutionary left would destroy democracy. Given the crimes of the Stalinist regimes, including East Germany, which at that time surrounded West Berlin, that illusion was easy to make stick. It was imperative, then, that among the key theoretical documents Mandel drafted for the Fourth International in 1977 was one on Dictatorship of the Proletariat and Socialist Democracy, discussed at the World Congress in 1979 and eventually adopted at the 1985 congress.

What Mandel wrote for internal-organisational educational meetings and as public agitational interventions were always keyed into the developing consciousness of radical movements, and so we can see a dialectic in his writing between general theoretical principles and specific questions.

That need to find a way to make Marxism accessible and relevant to those engaging in struggle, to experienced workers who have been building mass organisations, and to those coming into revolutionary politics for the first time, is explored by Kellner in an interesting discussion of what “education” meant for Mandel. Kellner points out that while some Marxists begin with rather abstract and difficult-to-grasp economic phenomena, such as the “law of value” or the tendency of the rate of profit to fall as capital increases, Mandel is often more concerned with explaining how we have come to this situation.

How capitalism develops and the consequences that it has for our lives also point us to the question of how capitalism may come to an end. Mandel always had his eye on the nature of capitalism as a historical process, something that we are often deeply involved in reproducing but can critically reflect upon and transcend. It is in that sense, Kellner notes, that Mandel is also, to his core, a radical socialist humanist; complaints that he was sometimes too “optimistic” are all to do with that humanist faith in the capacity of human beings to find a way out of this mess, a way to socialism instead of barbarism.

Reflection and critique

This book is not uncritical, though, as Michael Löwy points out in his introduction to this English edition of the book, which was first published in German in 2009, it could have woven its criticisms of Mandel into each of the chapters on different aspects of his work. As it is, the book carries the traces of its initial academic format, with an opening literature review focused on the number of citation counts in German libraries, then a presentation of Mandel’s life—something which is explored at greater length by Jan Willem Stutje in his excellent 2009 Ernest Mandel: A Rebel’s Dream Deferred—and then some critical remarks.

Critical reflection as well as admiration is the best way of acknowledging Mandel’s contribution to the development of revolutionary Marxist thought and practice, and Kellner picks up and extends some of the elements of that kind of thoughtful critical reflection that were contained in contributions to the very interesting volume edited by Gilbert Achcar in 2000, The Legacy of Ernest Mandel.

Mandel was a revolutionary humanist. It is that very humanism, and the insistence that it is only internationalist collective self-conscious activity by the oppressed committed to building an alternative to capitalism that will enable us to put an end to the different forms of barbarism that already characterise human history, that is subjected to some criticism by Kellner in this book. It should also be said that this criticism is itself from a particular cultural-political standpoint, not only Kellner’s but also that of sections of the German left.

“Mandel was a revolutionary humanist. It is that very humanism, and the insistence that it is only internationalist collective self-conscious activity by the oppressed committed to building an alternative to capitalism that will enable us to put an end to the different forms of barbarism that already characterise human history, that is subjected to some criticism by Kellner in this book.”

The critique seems to boil down to a complaint and an accusation: that because Mandel was Jewish, he should have spoken at greater length about the Holocaust. Kellner is here expanding some of the criticisms made by Norman Geras (in a contribution to the Achcar book) that, in some way, because he did not write specifically about the Holocaust, Mandel did not take it seriously as such. Mandel argued that the depths of barbarity that the Holocaust expressed were an indictment of the capitalist political-economic system that incited and benefited from it. He did not, as Geras and some other critics would argue, thereby “relativise” the Holocaust.

Optimism of the will

It was clear from his many writings on different forms of barbarism to which capitalism has already sunk that Mandel was horrified by the irrationality that was unleashed, permitted, and even encouraged by those intent on finding scapegoats for the crises of capitalism. In the process, the vast toxic reserves of Christian antisemitism were drawn upon and put to work in Europe through a machinery of mass murder. It is not at all to “relativise” the Holocaust to argue, for example, as Mandel did, that were fascism to triumph in the United States, the brutality of racist extermination would be more than matched there. Mandel was an internationalist, attentive to the manifold brutalities of capitalism and imperialism and to the dreadful crimes committed in their names, as well as in the names of the “Left”.

Mandel’s energy was directed to a form of analysis—of capitalism and late capitalism—that would enable us to really confront what has already been present for some time inside capitalism as forms of barbarism. There is a resource archive on Mandel’s work where you can download texts in different languages and a recent three-volume series of his writings at Resistance Books. Kellner’s book is a useful contribution to the task of acknowledging and taking forward what Mandel has given us.

Art (47) Book Review (102) Books (106) Capitalism (64) China (74) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (43) Economics (36) EcoSocialism (48) Elections (75) Europe (44) Fascism (52) Film (47) Film Review (60) France (66) Gaza (52) Imperialism (95) Israel (103) Italy (42) Keir Starmer (49) Labour Party (108) Long Read (38) Marxism (45) Palestine (133) pandemic (78) Protest (137) Russia (322) Solidarity (123) Statement (44) Trade Unionism (132) Ukraine (324) United States of America (120) War (349)

Latest Articles

- France after the elections: How should the radical left act?In the wake of the National Assembly’s dissolution and new parliamentary configuration, La France Insoumise (LFI) should adopt a clear stance of radical opposition, emphasizing its commitment to anticapitalist principles and democratic reforms while avoiding any compromise with the existing government unless it secures absolute majority support from the populace, argues Gilbert Achcar.

- Why Socialists Oppose the Two‑Child Welfare CapIn this article, Simon Hannah explores why socialists vehemently oppose the government’s two-child welfare cap, arguing that it stems from austerity measures and reactionary views on the poor.

- Hands off Trans KidsA pamphlet from Anti*Capitalist Resistance.

- Two Child Benefit RevoltDave Kellaway responds to the revolt by Labour MPs and others to the Labour government keeping the Tories’ hated two child benefit cap.

- The beginning of the end of China’s rise?This is the second interview in a two-part series. The first interview (“Opposing US militarisation in the Asia-Pacific should not mean remaining silent on China’s emerging imperialism“) covered the nature of China’s state, its status in the world today, and implications for peace and solidarity activism.