Delia’s face dominates this movie. It is her face that we see continually being hit by her brutal husband. A face that is riven by fear, tension, pain, and tears but also hope, pride, resilience, and rare smiles. Paola Cortellesi brilliantly expresses these emotions from one moment to the next. The camera follows her face and her movements in nearly every scene. Already a well-known singer and very successful TV and film actress, this film has been her labour of love. This is her directorial debut.

“Delia’s face dominates this movie. It is her face that we see continually being hit by her brutal husband. A face that is riven by fear, tension, pain, and tears but also hope, pride, resilience, and rare smiles.”

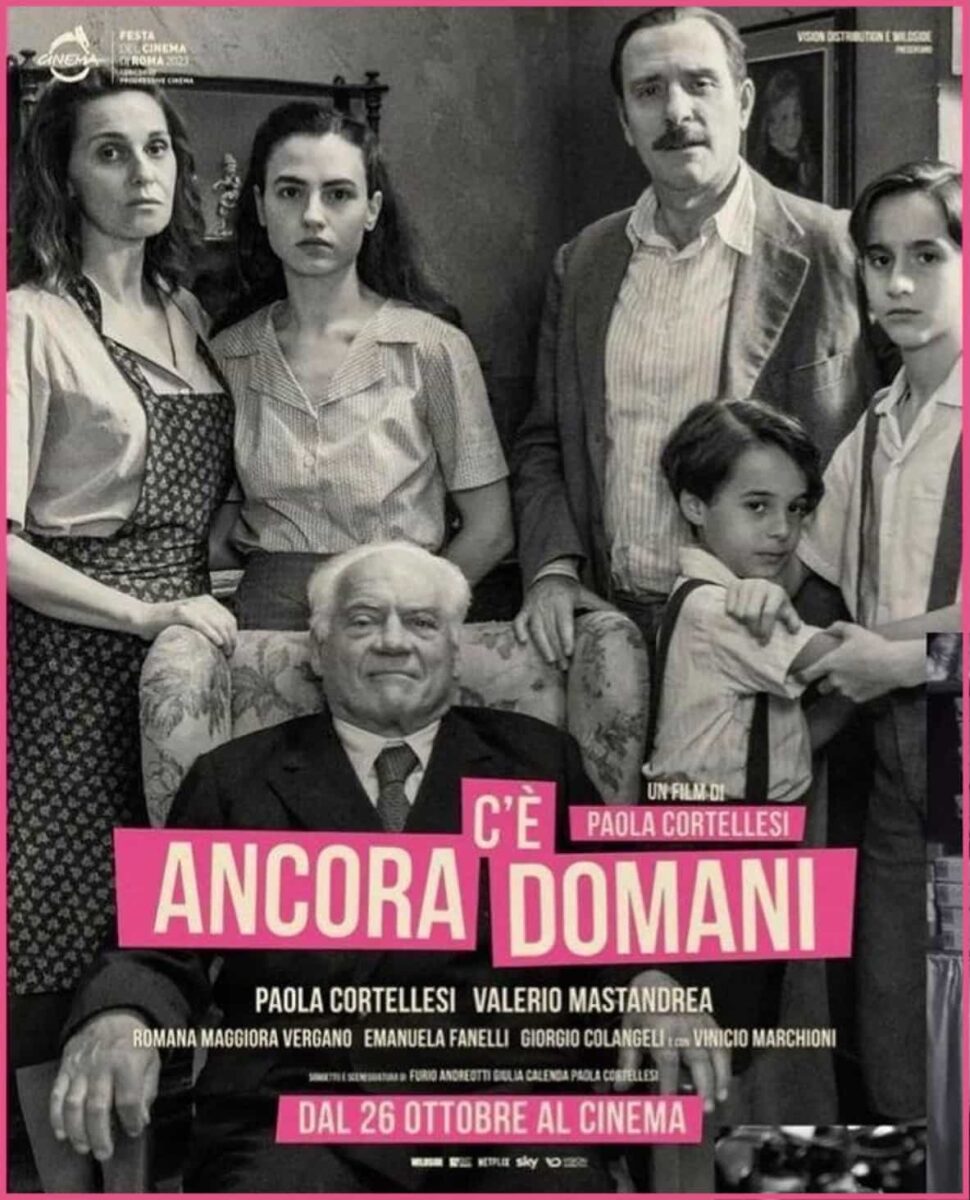

For the first fifteen minutes or so, you could be forgiven for thinking that a cinematic Tardis had taken you back to the golden age of 1940’s Italian neo-realism. Cortellesi chose black and white and rejected a wide-screen format to immerse us in the Italy of 1948, immediately before the referendum on whether to abolish the monarchy. This was the first election in which women could vote.

As we follow Delia making a meagre breakfast, getting her kids to school, and then grafting for a pittance in various odd jobs, we see the same Roman streets as De Sica showed us in the story of the father searching for his lost bicycle in The Bicycle Thieves. Anna Magnani comes to mind too in Rossellini’s Rome Open City. These directors shot in the streets because they wanted authenticity and could not afford the studios or expensive equipment. Long takes, unknown actors, and working in ‘real time’ episodes also saved money and added realism. Ken Loach recognises the influence of this cinematic current.

Here, the skills and expertise of today’s set and location designers allow the illusion of post-war Rome to be recreated very effectively. The long opening sequence places the viewer immediately into the drama of Delia’s life and sets up the story lines. She is trapped, but we see her putting money secretly aside, and she is most concerned that Marcella, her daughter, does not end up in the same situation as she is in. Ivano rejects Marcella’s desire to continue her education past the elementary level because of the cost. He is happy to accept her wish to marry the son of the local cafe owner, not because he particularly wants to meet her needs but because the link-up with this family would give him some security. The film skillfully contextualises the feminist theme within the stark inequality of the time, the divisions arising from the war, and the resentment against those who collaborated with the fascists or made money in the black market, like the cafe-owning family.

“The film skillfully contextualises the feminist theme within the stark inequality of the time, the divisions arising from the war, and the resentment against those who collaborated with the fascists or made money in the black market, like the cafe-owning family.”

Early on, it was also established that the local mechanic, who was the childhood sweetheart of Delia, is still in love with her and that she is still attracted to him. Like many other workers, he is looking to move north to get a better life. The story and tension in the film are tied to whether she makes the decision to go north with him and also how the situation with her daughter is resolved.

From the moment she wakes, the tone is set as Ivano, her husband, another great performance from Valerio Mastandrea. All his dialogue is composed of putdowns, insults, orders, or sarcastic criticism. The only instances of any tenderness are in moments of remorse following the physical abuse of Delia.

Another daily task for Delia is to care for Ivano’s father, Ottorino. It was seen as customary for the wife to care for her father-in-law. We see how patriarchal violence is handed down through the generations. At one stage, Ottorino is concerned that his son is hitting Delia too much; apart from anything else, he says it disturbs his rest. His advice is not to regularly hit her but to give her a really good battering less frequently, like he did to his wife, so that she is kept under control.

Cortellesi makes the film more than just a hommage to the neo-realist era. The camera’s modern flexibility allows her to create brief imaginative moments from both Ivano and Delia’s points of view. Popular songs provide a soundtrack that you do not generally find in the more austere neo-realist genre. We are jolted out of any nostalgic view of the issues, partly by the inclusion of 16 different songs (complete or in extracts). They range from those contemporary to the drama in the first part of the film to quite modern songs such as Lucio Dalla’s La sera dei Miracoli or Daniele Silvestri’s A Bocca Chiusa. The latter has a specific reference to the climatic ending. It is as though the director wants to say this is a movie not just about 1948 but about what is happening to women in a different form today.

The narrative tension of the film is maintained throughout very skillfully. Will Delia escape with her teenage love? Will Marcella’s engagement work out and help the family? A pivotal scene—one that will linger in your memory—is when Delia observes through an open door an interaction between her daughter and fiancé. It opens her eyes, and she makes up her mind about what to do. The ending is adroitly engineered so that you are completely thrown off track. You were expecting something else, only to understand its deeper political meaning. It is unsentimental but hopeful.

The only clumsy part of the plot is the role of the black American military policeman’s role in the resolution of Marcela’s engagement. It lacked credibility, although it did drive the plot forward.

We often overlook the extreme living conditions of people both here and in Italy in the immediate post-war years. Rationing continued in Britain until 1954, and the housing stock only began to improve during the 1950s. In Italy, the majority of the population still lived in rural areas, and most worked the land. The film shows the extreme class inequality through the contrast between the cafe-owning family and Delia’s during the engagement Sunday meal. This would be modified as a result of the post-war boom and the struggles of the trade unions.

However, while women in Italy have made many gains, they still suffer from one of the lowest participation rates in the employed work force. There is plenty of evidence today of women, particularly in the poorer South, doing a similar array of odd jobs in the informal economy in order to get by. Just as we see the boss in the film explaining to Delia that the new man she is training is paid more than her because he is a man, women in Italy today still tend to be paid much less on average than men.

Abuse and violence against women are not as endemic as we see in this film. Women have organised to win reforms on divorce (1974) and abortion (1978) but are still mobilising against sexual violence and femicide. The film has helped keep the issue alive, as it has had a mass audience in Italy far beyond any intervention that the feminists or left could have achieved.

While the post-fascist premier, Georgia Meloni, has spoken up against male violence and even adopted some legislative measures, she has recently agreed to allow anti-abortion ‘counsellors’ to operate in the clinics where women go for terminations. She is also promoting ‘family friendly’ policies to increase Italian ‘fertility’, which her party thinks is threatening the Italian nation and its identity, ‘under threat’ from migration.

In an interview with the BBC, Cortellesi reveals her motivation for the project:

The whole project came about because I was reading a book on women’s rights and my daughter could not believe that there was a time when our rights were not enshrined in law. So it occurred to me that we had to talk to the younger generation and make them understand that their rights are not taken for granted. Just because we have achieved something does not mean it will be like that forever. I wanted, in a way, to start passing the baton to a younger generation.”

This film represents a stunning debut for Cortellesi. It accurately evokes the difficulties and hopes of a particular period and implicitly relates to today. Let’s hope she continues to make more films.

“Just because we have achieved something does not mean it will be like that forever. I wanted, in a way, to start passing the baton to a younger generation.”

Art (47) Book Review (102) Books (106) Capitalism (64) China (74) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (43) Economics (36) EcoSocialism (48) Elections (75) Europe (44) Fascism (52) Film (47) Film Review (60) France (66) Gaza (52) Imperialism (95) Israel (103) Italy (42) Keir Starmer (49) Labour Party (108) Long Read (38) Marxism (45) Palestine (133) pandemic (78) Protest (137) Russia (322) Solidarity (123) Statement (44) Trade Unionism (132) Ukraine (324) United States of America (120) War (349)