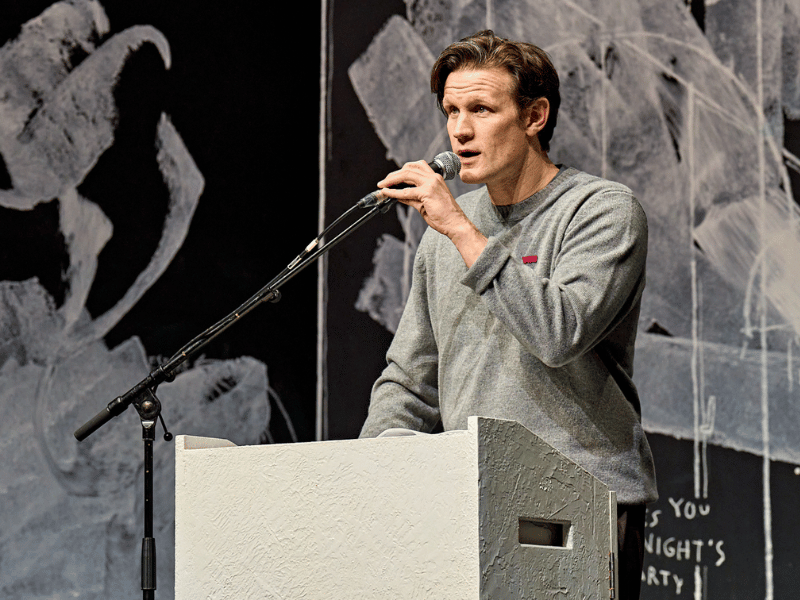

There is a version of Ibsen’s An Enemy of the People in London that is simply unmissable. It is an adaptation of the original Ibsen story about a town doctor who discovers that the water supply to the hugely popular spa is poisoned. For Dr. Stockman, played by Dr. Who’s Matt Smith, this is initially a simple case of fixing a public health issue, but his friends warn that this information will prove explosive. So it does. Dr. Stockman’s brother is the mayor, and to close the baths to fix the water problem would likely ruin the town economically. The cost of fixing the issue alone would be a huge expense.

So the medical problem becomes political, battle lines are drawn, and public health versus local resources and business interests are diametrically opposed.

Dr. Stockman’s partner is a part-time teacher who talks about the recent strike over pay. She is struggling with a small child and little income; they rely on Dr. Stockman’s wages to survive, but his job is the medical director of the very spa that is poisoning its visitors. The personal clash of principles versus pragmatic survival is also at play here.

This isn’t the original Ibsen; the story is the same, but the production is updated by the German theatre director Thomas Ostemeier, a radical who made his name doing modern anti-capitalist versions of old classics, both Ibsen and Shakespeare.

“This isn’t the original Ibsen…This version breaks the fourth wall in the most vicious way.”

I hadn’t read about the production, so I didn’t have a clue what they were going to do. This version starts off with a quote from the revolutionary anarchist from The Invisible Committee’s 2008 publication, The Coming Insurrection:

“I AM WHAT I AM: the latest marketing slogan by an American sports shoe producer, not simply a lie, not a simple advertising campaign, but a military campaign, a war cry, directed against everything that exists between beings, against everything that circulates indistinctly, everything that invisibly links them, everything that prevents complete desolation against everything that makes us exist and ensures that the whole world doesn’t have the look and feel of a highway, an amusement park or a new town: pure boredom, passionless but well ordered, empty, frozen space, where nothing moves apart from registered bodies, automobile molecules, and ideal communities.”

The Invisible Committee

At the start of the second act, Dr. Stockman (Matt Smith) faces the audience and is going to deliver a speech about how the town’s water supply is poisoned, but the politicians and business leaders won’t do anything about it because it would cost too much money. Instead of talking about that, he goes into a 10-minute-long revolutionary speech condemning the current state of the world, modern capitalism, the wealth gap, the crushing of democracy, the spread of disinformation, the callous attitude towards pandemics, the barebones wages and mental health crisis, the lying politicians, and the grift of the far right. But also the liberal majority, voting for political parties that won’t fix anything, consuming without care, unwilling to take a stand and challenge the system.

The speech was powerful and delivered directly to the audience.

This is the genius of the production; it breaks the fourth wall in the most vicious way. We are the townspeople; the choices that we must make over our communities, our health, our jobs, and our wages are all presented to us every day, just as the play confronts an ethical choice. The town is being shifted, and the agreements between the local politicians, businesses, medical professionals, and the public are being tested and shattered. The COVID pandemic haunts production: lives versus profit; make a choice. But that would be an easy choice. It is often your life versus your livelihood; can you afford to lose your job to do the right thing? This too brings up the environmental crisis, the scarcity of choices in a capitalist system where our livelihoods are predicated on the smooth operation of the capitalist machine even as it poisons us or destroys the environment.

“The COVID pandemic haunts production: lives versus profit; make a choice… Can you afford to lose your job to do the right thing?”

This is the connection to The Invisible Committee’s manifesto: that the society we live in has atomised our natural social cohesion and the need for truth when it comes to politics and economics. Instead, the truth becomes an inconvenience, something that gets in the way of the necessary business of economic survival. The journalists are in on it too when they find out the cost of fixing everything will likely bankrupt the town. Dr. Stockman becomes the enemy of the people, even though he is the only one speaking the truth. When politicians, businesses, and journalists are all aligned against you, doesn’t that draw revolutionary conclusions? It should do.

“…the society we live in has atomised our natural social cohesion and the need for truth when it comes to politics and economics. Instead, the truth becomes an inconvenience…”

The speech gets huge cheers from most people. Then another actor takes the microphone and addresses us, all 650 people, and says, If you cheered for that, put your hand up. We do.” Ok, microphones will be going around. Tell me why you agreed with what he just said.” Suddenly we are in audience participation, and some people put their hands up to speak. Inevitably, I do as well—never miss an opportunity to spread the word! I said I agreed with Dr. Stockman that we live in a world made sick by capitalism; they cannot fix the climate crisis. Shell abandoned its green investment wing because it wasn’t profitable. The ruling class divides us to control us; we are taught to hate foreigners, refugees, and migrants so those in power can keep control. I finished by saying that if the town couldn’t fix its water supply, then what does that tell you about how fit for purpose our current economic system is? I got a very good round of applause and some whoops.

A few more people spoke, and then they carried on. The twist at the end imposes another ethical choice on the Stockman’s: stripped of everything, will they too betray their principles for a get-out, a second chance? The play offers no easy answers, forcing choices shaped by the contradictions between need and principle, between resolve and capitulation.

“The play offers no easy answers, forcing choices shaped by the contradictions between need and principle, between resolve and capitulation.”

The play was reminiscent of the recent revival of Accidental Death of an Anarchist, which Dave Kellaway reviewed for ACR last year. That play too demanded answers from its audience: how long will we accept endless inquiries and reviews as the truth is buried under lies and red tape, as justice is delayed and therefore denied, when the entire bureaucratic apparatus is there to slow everything down to a crawl to prevent any spontaneous outburst of action?

After it was over, a couple of people came up and asked me if I was a ‘plant’ in the audience—perhaps a sign that I did a good job. I left the play really feeling like the polarisation in our society was accelerating. So many cultural signifiers point to the need for radical change in the air, if only we could build movements and political organisations that could rise to the challenge. Even productions in the West End of London cannot ignore the mood—the hideous feeling that we are trapped in the belly of a dying monster, but people cannot see a way out.

If you can get a ticket for An Enemy of the People at the Duke of York Theatre in London, then I recommend it. If the production opens in a place near you, go agitate. Draw out the contradictions. Offer solutions. The play demands it of us.

Art (47) Book Review (102) Books (106) Capitalism (64) China (74) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (43) Economics (36) EcoSocialism (48) Elections (75) Europe (44) Fascism (52) Film (47) Film Review (60) France (66) Gaza (52) Imperialism (95) Israel (103) Italy (42) Keir Starmer (49) Labour Party (108) Long Read (38) Marxism (45) Palestine (133) pandemic (78) Protest (137) Russia (322) Solidarity (123) Statement (44) Trade Unionism (132) Ukraine (324) United States of America (120) War (349)