This piece develops from a talk I gave at a meeting discussing the economic situation in Britain and how this issue will play out locally in London. It also provides some suggestions on how we can develop grassroots local campaigns in local communities to fight back against continued attempts to pass the economic crisis and financial pressures at the local government level onto the working class. Essentially, the British government is continuing austerity. While initially introduced in 2007–2008 to pass on the crisis to the working class, austerity is continuing with the same goal, making the workers pay for supply-side economic policy decisions by successive Tory governments.

The British Economy: Incompetent Economic Policies and Economic Stagnation

The British economy is essentially stagnant; growth is extremely low. The way in which this government (and, for that matter, successive Tory governments) attempts to squeeze wages while trying to increase profitability, which they believe will be then reinvested productively in the real economy to create growth.

“The British economy is essentially stagnant; growth is extremely low. The way in which this government (and, for that matter, successive Tory governments) attempts to squeeze wages while trying to increase profitability, which they believe will be then reinvested productively in the real economy to create growth.”

The problem is that this is not happening; financialisation and speculation in financial markets are the places for investment by the majority of those with wealth, rather than investing in the real economy. So, the British government’s supply-side approach has just not worked if they are hoping for increased economic growth.

The reason for this can be found in any first-year introductory macroeconomics textbook (one wonders what is actually taught in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics courses in Oxbridge and other elite universities in which so many British politicians have their degrees). As one would have been taught in basic macroeconomics, it is effective demand (demand backed by the ability to buy) that drives investment in the short and long term; it is not savings, which is argued by Say’s Law; the classical version is that production creates demand, and the neoclassical version is that savings determine investment, as that is concentrating on the capital markets. In the long term, theoretical debate still exists about whether Say’s Law holds (Keynesians, New Classicals, New Keynesians, and Neo-Keynesians) or whether it is, as Post-Keynesians maintain, expected demand (and we can add expected profitability, which Marxists argue) that drives investment (this would be taught in intermediate or advanced macroeconomics or even MA macro).

As such, even though everyone (except New Classicals, and they say a lot of nonsense) agrees investment is what leads to growth in the short term, neither trickle-down economics, nor its more general expression, supply-side economics, can be demonstrated to lead to economic growth either in the short or long term (the British economy is a perfect example of why this doesn’t work), despite the work of many luminaries in economics. Alas, economic theory and economic reality often have little to do with each other.

Even with some government investment in the public sector after years of underfunding, we are seeing limited growth as there is so much investment that needs to be done. The public-private partnerships set up under New Labour to create investment in the NHS have not only created massive debt repayments that NHS trusts need to repay, they drain the funding coming into the NHS. Moreover, promises of the government building new hospitals under Boris Johnson have not materialised. Hospitals are in need of massive capital investment and money to hire new doctors and nurses where there are significant shortages of personnel.

The Tory government’s refusal to increase wage incomes of the majority beyond inflation (so the minimum wage has been increased by the Tories but insufficiently to overcome inflation, which means that money wages have not increased in real terms). This has also impacted growth and led to insufficient workers in an economy dependent upon foreign workers for many jobs, and the low wages on offer are not enough to tempt enough foreign workers to come to Britain to work in the care sector, for example (there are an estimated 152,000 vacancies in the care sector) and very high turnover rates, with an estimated 390,000 leavers of the profession over 2022–23.

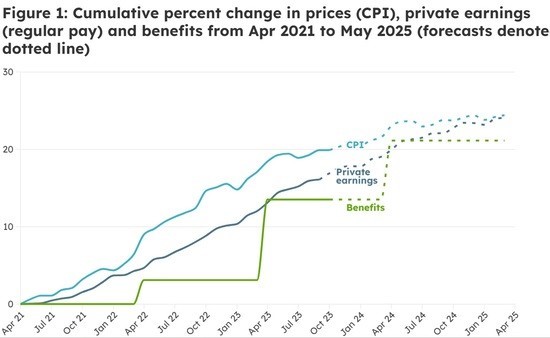

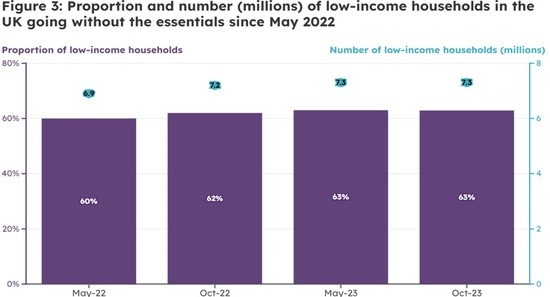

From Joseph Rowntree Foundation:

To add to the problem, the British government has just passed a new law requiring you to earn at least £38,700 a year (starting in spring 2024), up from £18,600 a year (for a family visa to work). It is not yet clear how this will apply to visa renewals. The average UK care worker’s salary is £23,410 per year, with a starting salary of £21,133 per year and experienced workers earning £38,874 per year (just clearing the threshold to bring your family).

As I said above, not understanding the obvious is something that successive British governments excel in (along with in-fighting among the various ideological groupings in the Tory party, from the so-called One Nation Tories to the far-right “5 families”—if that sounds like a group of mafiosos, that is completely appropriate; literally, they are fighting to see which group of right-wing creeps is actually further to the right).

Since it was all over the newspapers and in the MSM in Britain and the US, you may have noticed that Britain’s growth was negative in October, and this was due to decreased production in services and construction and demand for these outputs due to the high level of interest rates. Britain predominantly produces services rather than goods, and high interest rates have impacted the demand for services.

High interest rates exist due to the erroneous way in which international banks have tried to address inflation, which is raising the interest rates, which would have worked if the inflation was driven by demand rather than breaks in supply chains. The point of increasing interest rates is that they serve as a brake on economic growth, which is possibly appropriate if demand is driving inflation. High interest rates mean that many businesses (especially smaller ones) will borrow less (as it is more expensive), the value of debt will be higher if debt has to be renegotiated, and consumers are more reluctant to borrow as it is more expensive if you are using credit.

Privatisation has put access to services (e.g., childcare, early childhood education, and social care) out of the reach of many working class people whose wages are stagnating despite the wage gains won by unions in the public sector (whose wages have been below the private sector since before the pandemic). This also means that more and more women have to drop out of work to provide care for family members with sickness and infirmities (this has increased due to long-covid) and childcare and early childhood education for their children. The government’s refusal to provide for childcare and early childhood education and to provide basic guaranteed services rather than punish people for not working.

That is why the economy is stagnating in general, but there are also specific things in Britain relating to Brexit because Britain was part of supply chains in general production across Europe, and that has become more expensive due to Brexit, which has led to increased prices for food and imported consumer goods due to the increased price of oil (which has stabilised) and the need to purchase food from farther away due to climate change and increased prices due to Brexit.

Blaming the Victims

The absurdity of blaming low productivity and economic growth on the working class, predominantly those that are not in employment (without offering, e.g., childcare to get unemployed women into work or sufficient support for disabled people, in the form of personal assistants, etc.), has continued a punitive regime against the poorest in society. This has been the case since the introduction of universal credit during austerity. Privatisation of parts of the public sector that were deemed profitable has not led to increased economic growth and qualitative and quantitative increases in the service sector, which is the predominant economic sector in Britain; privatisation has led to both the destruction of wages and working conditions as well as insufficient quantities and qualities of service production that are needed. The privatisation of work and services in the NHS has undermined the NHS itself, which is unable to function; the wage increase caps have undermined wages and conditions of work (as parts of the work force, especially at the lower levels, have been privatised).

“The absurdity of blaming low productivity and economic growth on the working class, predominantly those that are not in employment (without offering, e.g., childcare to get unemployed women into work or sufficient support for disabled people, in the form of personal assistants, etc.), has continued a punitive regime against the poorest in society.”

The government’s autumn statement is based on an erroneous understanding of economic growth, which should come as no surprise. They have chosen to decrease taxes (specifically National Insurance) and penalise disabled people, single mothers, and the unemployed. Decreased National Insurance revenues mean there is less money to spend on the criminal justice system, the NHS, education, and services like early childhood education and social care. It also means less money goes to local councils. Even more cynically, since the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Jeremy Hunt, knows that they will not be in power, they are cutting tax revenue this year and putting in cuts to cuts in public spending, which are due to come into force in 2025 when they will be out of power, hence dumping more misery onto the population when the Labour Party is in charge. This continues the cycle of destruction of the public sector and social welfare state and shifts the crisis onto the backs of the working class, especially the poorest, the disabled, and women (especially single mothers) in the country.

Rather than acknowledge their failures (including Brexit) for economic stagnation, they are blaming (of course) those that are out of work for both low productivity and economic stagnation, which is nonsensical. Productivity is not based on how many people are actually in employment; this is nonsensical. There are several things responsible for low productivity stemming from the neoliberal economic model, which has encouraged the destruction of wages and working contracts. The type of work available that is based on precarity (zero-hours contracts) not only undermines wages, but it also undermines productivity because the workers are not in jobs long enough to develop the skills and knowledge that actually would increase productivity, as anyone who has read Adam Smith’s discussion on growth, productivity, and wages (so the first 3 chapters on economic growth and the chapter on wages in the Wealth of Nations) would know (or who read mainstream efficiency wage arguments).

The other thing that the race to the bottom does is that it has made wages so low that the introduction of technology (and that combined with labour is what leads to increased productivity and growth on the micro level) does not make economic sense because labour is treated as a cost in this type of reasoning; so lowering costs has relied on cutting wages and undermining working conditions. So, the destruction of the public sector, leading to far too few workers still employed in the public sector to do the actual work needed to be done, has already had a massive impact on both the production of and access to services produced by the public sector. This, combined with the privatisation of the service sector, has made access to essential services even more difficult to obtain, putting childcare out of the reach of many families. Working to pay for child care does not cover the rest of the essential goods that you need. Increasing sanctions and demonising the working while making the Tories feel better increases the misery and immiserisation of the working class.

As Joseph Rowntree Foundation shows:

The cost-of-living crisis still exists in Britain. Despite the wage gains by public sector unions after a series of strikes, most of these gains did not go beyond the level of inflation and did not make up for losses in back pay due to caps on public sector wages. For non-unionised workers (which are the majority), wages are still insufficient to cover increased costs of goods and services. This means that despite being at work, many workers are struggling to cover the basics: private rents have risen along with interest rates (greedy landlords are using interest rate increases to hike rents); food prices are still rising; and energy and electric costs are still high.

Moreover, disabled people are being threatened with literally forced labour as part of government policy. Those that are unable to labour at all are “covered,” according to the government, but benefit increases are only at 6.7% compared to the 8.5% increase for pensioners due to the triple lock, and that means that benefits still do not cover the increased cost of living even though the increased inflation has lessened.

We need to understand inflation as a battle between the capitalist class and the working class. Increased prices lead to increased profitability (note this doesn’t hold for small businesses that actually have increased debt and probably decreased production as a result of lowered expectations of demand and profitability). What has happened is that this battle has been won by the capitalists at the expense of the working class; strikes have enabled a gain in some areas in wages (especially in the public sector), but the increased profitability has been incredible. Once again, the impact of crises is passed onto the working class; this was evident during austerity following the 2007–08 crisis, and it is continuing again today. Do not be fooled; austerity is continuing, and once again, austerity is geared towards passing the crisis onto the working class, which is barely surviving as it is. Food bank usage has become normalised in what is nominally one of the richest countries in the world.

“We need to understand inflation as a battle between the capitalist class and the working class. Increased prices lead to increased profitability (note this doesn’t hold for small businesses that actually have increased debt and probably decreased production as a result of lowered expectations of demand and profitability).”

How will all this play out locally in London

I would strongly suggest that comrades read the article in Tribune Magazine that discusses England’s collapsing local governments, bankruptcies, and the resulting spending cuts by local councils, as it explains not only the background for the current situation but also what is going to happen. The bankruptcy of Birmingham City Council (the second-largest city in Britain) may be one of the first, but it will not be the last.

“[…] local government in England has had its funding cut by £15 billion between 2010 and 2020. That’s a real-term cut of 20 percent. And to make matters worse, cuts hit deprived urban authorities the hardest.

With England’s population increasingly ageing and unwell amid the NHS’ slow-motion fiscal catastrophe, the cost of those statutory services is ballooning just at the moment when funding has been slashed. All discretionary spending, whether on libraries, economic development, or local public services like bin collection, has been squeezed.

The costs of temporary accommodation, statutorily required for housing those declared homeless in the absence of sufficient social housing or Housing Benefit rates, are soaring, reaching at least £1.6 billion in 2021–22. This year, local authorities in England will spend nearly a third of their budgets on social care, but we are still far from meeting the cost of future demand, let alone improving service quality or covering its full cost.”

There are several things that will happen as the local council’s finances become more and more strained. They will cut any services that are not statutory (think of libraries, community centres, after-school activities for children, etc.). If there are services that are still covered by in-house local councils (e.g., childcare, locally run and funded care services, libraries), the local councils will move towards private agency provision. This is serious, as the wages paid by agencies are far lower than what workers get paid in-house. As an example (and I know it is not perfect), Barts Hospital Trust runs Whipps Cross Hospital (and several other hospitals). At Whipps Cross, half of their staff of cleaners and domestic workers, cooks, porters, and security were removed from the NHS and were made agency workers (and these are not zero-hour jobs). The workers made 17.5% less wages (also think of losses of NHS pensions and benefits) than those still employed by the NHS. The workers, Unite Union and Unite Community members in various London areas fought back; it took over 3 years, but the workers won, got back pay, and were brought back into the NHS. I mentioned Unite Community as not only did we build support locally for the strike, they were the people calling union members to tell them to vote for the strike. This has been done elsewhere, where the Unite Community has called members of the industrial union where strikes are pending and asked them to vote. It is a way of bringing grassroots communities and activists together with industrial workers. If we can replicate this, we must do so; we need to build local community support for union strikes and workers. During the wave of strikes, many people were raising money for strike funds and to donate to local food banks.

Now let’s talk about local councils and the danger of bankruptcy for local councils. Since Birmingham local council has declared bankruptcy and six other councils have said they are in danger as well (and there are rumours other councils may follow), we are seeing serious concern about the impact of the financial crises of local councils on service provision. If local councils go bankrupt, they still must cover their statutory responsibilities to the elderly and children with special needs. Privatisation of services has already impacted children with special needs in terms of accessing support and assistance, as well as spending on Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND). There have been fights over the provision of SEND in Walthamstow, and there is a high probability that is the case in other areas.

“If local councils go bankrupt, they still must cover their statutory responsibilities to the elderly and children with special needs. Privatisation of services has already impacted children with special needs in terms of accessing support and assistance, as well as spending on Special Educational Needs and Disabilities (SEND).”

Who is not protected if local councils go bankrupt? Community centres, government childcare provision, after-school programmes, etc. Who else is also not protected? Those dependent on benefits, specifically disabled people, and mothers with children. They are already facing significant problems due to the transformations in Universal Credit Access announced in the Autumn Statement, where there is the danger of being forced into work.

“There are now a record 2.6 million people who are economically inactive due to long-term sickness and disability, almost half a million more than before the pandemic. The government is taking steps to reform the fit note process to support more people to resume work after a period of illness and expanding the Universal Support programme that matches those with health conditions and disabilities into vacancies. The government is also expanding the NHS Talking Therapies programme and Individual Placement and Support to help people with mental health conditions. The government will work with employers and business representatives to develop and promote best employment practices to support employees with health and disability issues. The government is reforming the Work Capability Assessment (WCA) so that more individuals, such as those with limited mobility and mental health conditions, receive the right support to find work where they can, rather than being automatically deemed unable to work or look for work. To better help the long-term unemployed into work, the government is expanding Additional Jobcentre Support, extending and expanding the Restart programme in England and Wales, and strengthening sanctions for those who choose not to engage with measures that help them find work. For those that cannot work for legitimate reasons there must always be a safety net. The government will uprate all working age benefits for 2024-25 in full, by September 2023 CPI inflation of 6.7%, and will continue to protect pensioner incomes by maintaining the Triple Lock and uprating the basic State Pension, new State Pension and Pension Credit standard minimum guarantee for 2024-25 in line with average earnings growth of 8.5% (Autumn Budget, p. 3).”

If you think this is a joke, it isn’t. I have a friend who was contacted by his local job centre in Birmingham to ask whether he can help provide care to others; to put this into context, this person has cerebral palsy, requires the use of a wheelchair for mobility, and needs support and assistance to get dressed, shower, and get breakfast in the morning. He also has a personal assistant throughout the day.

We can try to work at the grassroots local level, addressing local council budgets, care charges, further privatisation, and housing issues. Building local grassroots campaigns can build solidarity between people, have an effect on local council decisions, and actually help people materially. Council Tax is already unfair; many consider it a poor tax already in desperate need of reform. If local council budgets are going to charge council tax for those dependent on benefits, we must fight this.

We need to keep an eye on council budgets, specifically on council taxes, and changes in the amount that the poorest and those dependent on benefits are forced to pay towards council tax (pensioners are protected, but not those dependent on benefits generally). This attack is happening in Redbridge (the last time they tried to do this, we were able to fight back), and this time the “consultation” does not allow you to reject the budget and increases charges for those with the lowest incomes (incomes being wages and benefits).

The second point of struggle that has been going on for a while is trying to combat care charges levied against disabled people by local councils, which literally means food being taken out of the mouths of disabled people. If they have paid national insurance, if they have paid even a portion of council tax, they are now being forced to pay a third time for care services that they are guaranteed following the PIP assessment. In London, there are only two councils that are not forcing disabled people to pay care charges: Hammersmith and Fulham and Tower Hamlets (Lutfur Rahman raised council taxes on the highest bands to do this). This is a struggle being waged by disabled people’s groups; perhaps you can join with Inclusion London and other disabled people’s groups to fight together locally to stop care charges. Third, there is the issue of housing, evictions, and homelessness. If we can build community support to support those facing evictions and homelessness together with the London Renters Union, the Zaccheus Trust, Acorn, and Unite Community to build grassroots support, that would be amazing. Temporary accommodation is extremely expensive for what is often inappropriate and inadequate housing (whole families in one room, mixed accommodation with women and children, and single men). What needs to be understood is that those facing eviction are often single mothers with children, especially racialised women (lower wages in “unskilled jobs” or those unable to work due to childcare and caring responsibilities). Theoretically, councils have a duty to protect disabled people and young children from homelessness; unfortunately, that is not the case; they often have to be forced to do this by courts and the intervention of social services.

Private landlords are able to use Section 21 evictions (which even several Tory governments have promised to end; yes, we are still fighting for that) to throw people out with limited notice.

One victory we had was because the private landlord lied to the court (the family had been living there for a decade), saying that the evicted woman was not disabled despite her having a stroke and having to use a wheelchair for mobility—she was essentially wriggling up the stairs to her bedroom. Eviction resistance protected the house from the landlords changing the locks, and the local council was forced to find her new housing (what led to her eviction was that she had asked what responsibility the landlord had to make the house more accessible, and she was given a Section 21 eviction). This type of revenge eviction is not uncommon. Local councils have an obligation to ensure that disabled people have appropriate housing; this holds for adults and their families if children are disabled.

Evicted people (who are homeless, as many councils will not act until they are homeless) are often sent far away from where they lived, where they had family and community support; so, for example, Waltham Forest council has purchased housing in Stoke on Trent (135 miles away from Waltham Forest), where they have tried to dump people away from family, friends, and community support. We can help homeless people being sent out of London by fighting together with other groups working on housing issues. The strongest campaigns are those with the victims of the policy (evictees, workers, trade unions, disabled people), local community members, and organised local groups fighting on these issues.

Art (47) Book Review (102) Books (106) Capitalism (64) China (74) Climate Emergency (97) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (43) Economics (36) EcoSocialism (48) Elections (75) Europe (44) Fascism (52) Film (47) Film Review (60) France (66) Gaza (52) Imperialism (95) Israel (103) Italy (42) Keir Starmer (49) Labour Party (108) Long Read (38) Marxism (45) Palestine (133) pandemic (78) Protest (137) Russia (322) Solidarity (123) Statement (44) Trade Unionism (132) Ukraine (324) United States of America (120) War (349)