Smaller banks, bigger tanks.

An interesting article by “Bagehot” in the Economist last week on “shrinkflation” of the British state:

SHRINKFLATION IS A bane of the British shopper. For years, producers have quietly cut product sizes rather than raise prices. A multipack of Frazzles, a moreish bacon crisp, used to cost £1 ($1.36) and contain eight bags. Now it contains six. Cadbury’s Creme Eggs used to come by the half-dozen; now they come in fives. Quality Street, a chocolate box, weighed 1.2kg in 2009; today, just 650g. A box of Jaffa Cakes once contained a dozen biscuits; now just ten.

The logic of shrinkflation is that consumers are less likely to notice it than its alternative: higher prices. For years, the government has worked on the same principle. Taxpayers paid roughly the same, but state services withered. Now an era of price hikes in the form of tax rises has begun. In a nasty combination of inflation and shrinkflation, voters will be expected to pay more for less.

Frazzles aside (though they are indeed moreish), there’s a fundamental point here – and one that is being brought sharply into focus by the Russian invasion of Ukraine and what it tells us about Britain’s role in the world. Austerity of the 2010s variety is unlikely to make a simple return but different pressures on state spending are emerging.

Why austerity?

To see this, we have to put the austerity programme in its broader context. Austerity in Britain was always about more than an ideologically-driven effort to shrink the size of the state relative to the size of the national economy. Of course, it mattered that assorted latter-day Thatcherites in the Tory Party were noisily committed to shrinking the state, completing the revolution she supposedly began. But the breadth of the consensus on how big that state should be points to something deeper. Lib Dems swung into supporting it as the price of entry into the 2010 Coalition government. The actual programme of attempted deficit carried out by that government then closely matched the programme implied by Labour’s 2010 manifesto. This was a striking degree of consensus across the Westminster party system that was reinforced by the unhealthy dominance of the Institute of Fiscal Studies in providing economic analysis for media consumption, and a media caste that lacked the ability to seriously challenge any of it.

Austerity, then, shouldn’t be considered in isolation as an ideological quirk, or an outbreak of economic irrationality. It was systemic and determined far more by the primary institutions of the British state, notably the Treasury, than it was by the political parties. It arrived as part of a package whose primary aim was to restore the status and standing of Britain’s financial centre in a post-crash world, identifying the standing of that financial system as the fundamental guarantee of Britain’s continuing relevance as a major power. So austerity at home cut the costs of the state in general, but, most importantly, cleared the “fiscal space” needed to weather costs of another financial crisis in the future: were the financial system to fail again, austerity today acted as a guarantee it could be bailed out in the future, because the government was not carrying a large deficit and had committed to reducing its own debts. There would, therefore, be enough fiscal space on the national balance sheet to carry future losses.

Meanwhile, sitting inside the EU, but, crucially, outside the Eurozone, the City of London was to maintain and build on its role as the financial bridge from the EU into the rest of the world – where growth would be faster and, with faster economic growth, accelerating demands for financial services of the kind the City stood ready to provide.

To help see how austerity functioned, try a small thought experiment. Imagine that a British government after 2008 had decided to thoroughly ringfence the British financial system. In the place of the half-measures actually carried out, this hypothetical government would remove the systemic risks the internationalised financial system created by completely isolating it from the domestic economy. It would provide entirely new rules for internationally-focused finance, remove promises of government support, perhaps even – let’s really push the boat out – grant the internationalised part of the system its own new currency and central bank, turning the City of London, in effect, into a second Hong Kong. (This isn’t completely far-fetched: one plausible path for a post-independence Scotland is to do exactly this: introduce a new currency, cancel its legacy UK government debt, slash corporation taxes, loosen financial regulation.) The remaining domestic economy would carry on much as it is now, continuing to use high street banks and pound sterling. The collective balance sheet of the global-facing financial system would thus be completely separate from the domestic economy.

If it was politically feasible, could it work economically? Of course not, at least not for the financial system: this would be a sector now wildly overburdened with liabilities trying to use a currency no one wanted, with no one coming to its rescue in an emergency. The “security and stability” of such a system would be nonexistent; and, contrary to the predictions of Modern Monetary Theory, issuing more of the new money would only worsen its problems, devaluing assets denominated in its new currency relative to the rest of the world.

British financial services depend on the rest of the UK standing ready to bail them out. They needed integration with the wider British economy, and they needed a government prepared to act in their interests in a crisis. It is the fact that the world’s sixth-largest economy will, in extremis, be forced by its government to make good losses appearing in its financial system that granted that financial system such international strength.

Take away that promise – a promise typically implicit, disguised in the usual domestic political discourse, but made brutally real after 2010 – and hard limits to the expansion of finance appear. Or, as Bernard Jenkin, then chair of the Public Accounts Select Committee, put it in a moment of clarity in March 2015:

We still have institutions which are ‘too big to fail’ but with so much national borrowing capacity used up, they may prove ‘too big to save’ if it happens again.

Freeing up “national borrowing capacity” for future financial crises was the primary goal of austerity.

Strategy and finance

The post-2008 strategy for finance fitted into a wider orientation for the British state and economy. At a speech in October 2013 celebrating the Financial Times’ 125th anniversary, Mark Carney laid out the strategic goal with similar clarity. Placing the UK “at the heart of a renewed globalisation”, built around the largely untapped potential for financialisation in the developing world, Carney argued:

Suppose, for example, that UK-owned banks’ share of global banking activity remains the same and that financial deepening in foreign economies increases in line with historical norms. By 2050, UK banks’ assets could exceed nine times GDP, and that is to say nothing of the potentially rapid growth of foreign banking and shadow banking based in London.

Some would react to this prospect with horror. They would prefer that the UK financial services industry be slimmed down if not shut down.

And they’d be right to do so, since, as veteran Financial Times commentator Martin Wolf pointed out, growing bank balance sheets to this size “would turn the UK into the Iceland of 2007.” But as Carney continued:

It is not for the Bank of England to decide how big the financial sector should be. Our job is to ensure that it is safe. The UK can host a large and expanding financial sector safely, if we implement a reform agenda that extends well beyond domestic banking.

One part of that “reform agenda” were the changes to bank regulations Carney details. Another was the growth of swaplines and other mechanisms of international financial support, the 2008 temporary support measures made permanent just a week after Carney’s speech. And the final, unstated but critical element was the capacity of the British state itself to bail out the financial system.

The British state, under Conservative-led governments from 2010, pursued the strategy with alacrity. Austerity at home matched the turn into a “renewed globalisation” abroad, with China at its centre. Strenuous diplomatic overtures were made to Beijing. Since it seems to have been memory-holed, here, for instance, is former Chancellor George Osborne, speaking on the occasion of his visit to Urumqi, capital of Xinjiang, in 2015:

China’s emerging regions, like Xinjiang, hold enormous potential in the years ahead.

That’s why I wanted to come here today to see this place for myself, and highlight Britain’s absolute commitment to support the growth of Urumqi together with the whole of the Xinjiang region.

We are building an ever closer relationship with China – it’s a partnership that is set to unleash growth and help regions like Xinjiang where we know investment can make a real difference, as well as unleash new growth back home, in places like our own Northern Powerhouse.

(There are plenty more golden words over here.)

Things didn’t go entirely according to plan from about this point onwards. Brexit ended the City’s insider-outsider relationship with the EU. Theresa May, on becoming PM, pivoted against China and towards India. And the increasingly unpopular austerity programme – which had seen Jeremy Corbyn come close to Number Ten in the 2017 General Election – was decisively halted by Boris Johnson in autumn 2019 after his own arrival in Downing Street.

Today, despite (for example) the hugely costly decision to exclude Huawei from Britain’s 5G infrastructure, it may be that the China turn is the only part of the Osborne-era grand strategy that really lasts. London is the world’s largest centre for renminbi trading outside of China, and was the first place to offer sovereign renminbi bonds outside of China and Hong Kong, back in 2016. Chinese banks are busily expanding their operations there. Meanwhile, for all the ballyhoo from the Tories’ neoconservative wing, Johnson’s government is set to reopen crucial trade talks with China, paused since 2018. Entirely cynically – and we are dealing with entirely cynical people – it makes perfect sense for the UK government to stop providing financial services to a hostile Russia, and to tilt back into doing the same for neutral China, as is now happening.

“Shrinkflation” and rising costs

The war gets us back to shrinkflation. The 2010s revealed a political barrier to shrinking the state: at some point the domestic consequences of continual spending cuts become unmanageably large for Britain’s state managers. Do too much austerity, and something like Jeremy Corbyn emerges from the mists, threatening vengeance.

But another, more fundamental barrier is emerging. The costs of maintaining the economy are rising, appreciably. Covid was – and is – a radical version of this: the initial shock involved a phenomenal expansion of the state as a shock-absorber: in furlough payments and in healthcare, most obviously. But looking ahead, the long-term costs of managing this disease down to an endemic level are going to be significant, however much the government currently pretends otherwise. (Health Foundation estimated, last year, the costs to the NHS alone of about £10bn a year.) Throw in the rising costs of extreme weather and long run constraints on supply – seen most obviously, right now, in the shocks to energy and food prices – and the future costs of an aging society in its different forms, and the problems start to look acute.

Historically, from roughly the end of the nineteenth century, many of these costs of “social reproduction” were taken on by the state: increasingly, it was the government that bore the costs of education, health care, parts of childcare and so on. This was not a smooth or easy process. To turn the British state from its nineteenth-century nightwatchman role, occupying about 10% of GDP of which about half was spent on the military, to the welfare-oriented state of today, spending at least 40% of GDP of which about five per cent is military, took a succession of global crises and domestic political challenges. But the switch happened.

Alongside this rising expenditure, governments across the world shifted into more direct forms of economic intervention – not only paying for essential infrastructure, like urban sanitation systems, but taking ownership over companies and directly steering their spending and resources to support particular industries or even individual firms.

Out of fashion in the West since the late 1970s, interventions of this sort have reappeared with a vengeance in the last few years, even ahead of covid. The EU is tearing up its State Aid rules to allow greater collaboration and investment in its semiconductor manufacturers, identifying it as a crucial strategic industry for the bloc. The US administration, in one of the few parts of “Build Back Better “not to have crumbled, is pushing a $52bn subsidy in its domestic semiconductors, President Biden highlighting the commitment in his State of the Union address earlier in the week.

The driver, as should be obvious, is China, whose economic growth since 2008 has been very largely determined by the capacity of its government to intervene macroeconomically – mobilising immense sums to power the domestic economy through the initial crash – and industrially – supporting world-leading companies like Huawei with billions in subsidies, for example. At a national level, the neoliberal model of dependency on globalised financing and “level playing fields” (although never applied entirely consistently) is hard-pushed to compete in crucial technologies with deliberate, focused state interventions.

Meanwhile, the growth of swaplines between central banks, hailed by Carney and others as the development of a more secure global architecture for finance, look increasingly like allowing the emergence of regional financial systems, matching the regionalisation of the global economy. The actions taken by the joint powers against Russia, particularly in sanctioning its central bank, are likely only to reinforce this: the sanctions are effective to the extent that Russia, despite strenuous efforts since 2014, remained tied to the dollar-centred financial economy. The clear incentive, for every major regional power, is therefore to try and protect themselves against similar economic warfare in the future. (And their expectation, in a high-cost, low-growth world, should be for more warfare in the future.) Globalisation of the 2000s variety has peaked – and did so some time ago. The option for Britain to try and maintain its role as money-dealer to the world is less appealing as a result: there are still opportunities – look at China – but they are starting to look significantly reduced.

Tanks vs banks

Instead, something else is emerging. British military spending, even prior to the Russian invasion of Ukraine, was scheduled to increase sharply; after years of post-Cold War decline, continued under Tory governments from 2010, a striking cross-party consensus has now emerged on the issue. This was heralded first by the pointed commitment of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party to meet NATO’s military spending target of 2% of GDP, and to commit to the renewal of Britain’s Trident nuclear weapons system. Boris Johnson’s government had announced a 7.5% real terms increase in military spending over the next three years, and it is safe to assume Labour’s new front bench will not oppose rises beyond that point to counter presumed threats on the European mainland.

The steady re-militarisation of the economy was already gathering pace. The Defence Industrial Strategy, instituted by New Labour to co-ordinate defence production and procurement, abandoned by the Cameron/Osborne regime, was resurrected in March 2021 as the “Defence and Security Industrial Strategy”. More dramatically, after years of government opposition to state support for steelmaking, Sheffield Forgemasters was nationalised last summer, the Ministry of Defence taking ownership and announcing that it would “secure the supply of components for the MOD’s critical existing and future UK defence programmes.”

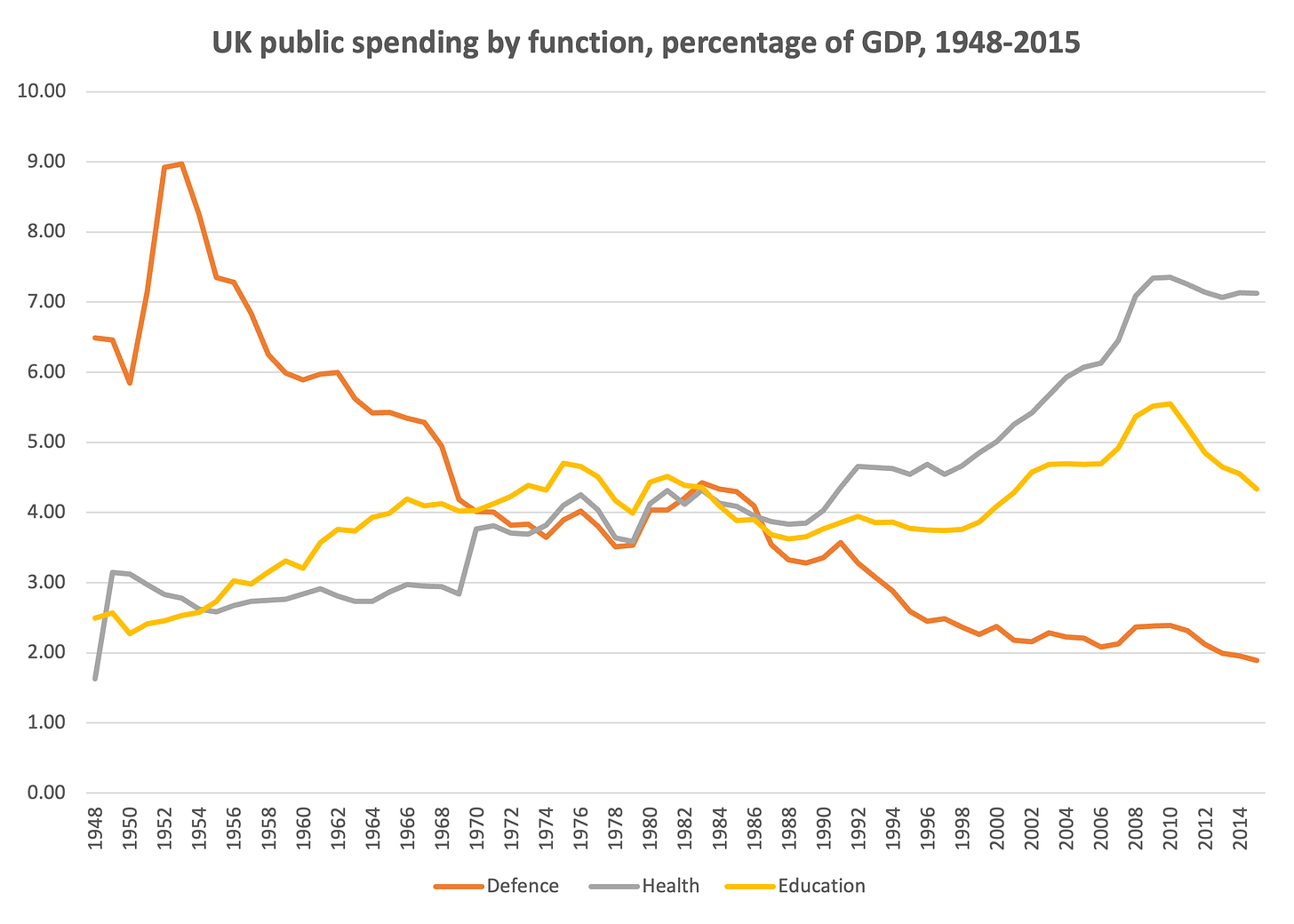

This commitment matches the government’s Integrated Review, which proposed Britain operating as a sort of aircraft carrier to the world, “projecting power” in the service of its assumed interests as far afield as the South China Seas. But supporting both a “tilt” to the Indo-Pacific and renewed military commitments in Europe will reinforce the pressures on public spending. The slide in military expenditure since the 1990s – the “peace dividend” of the end of the Cold War – turned largely into increased health and education spending, as the graph below illustrates; but once the pressures for financing of military and health and education start to combine, as they now threaten, the capacity of the British government to meet them will become stretched.

Source: Bank of England

And the limits to that capacity, as suggested above, appear not in the form of real constraints – the cupboard is not bare, Britain is a rich economy that can afford to make different choices about where and how it spends its resources – but as the political requirement to maintain sufficient space on the balance sheet for future financial failures. To put the point directly, the limits to its capacity emerge from the kind of integration the British state and its capitalist class have with the rest of the world.

To shift those capacity limits therefore requires a change in the form of integration. If military spending in the late nineteenth century could fit perfectly into a strategy to maintain Britain as a global financial centre, the Royal Navy guaranteeing the security of a global system dominated by sterling, the same mutual reinforcement may not apply in the early twenty-first. The Osborne-era strategy envisaged a smaller, lighter military machine matching a somewhat reformed (but still unstable) financial system oriented on global financial flows and economic growth in the rest of the world: smaller state, smaller army, bigger finance.

But successive deglobalizing blows have killed that aim, from the 2008 crisis, to Brexit, to covid, to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. In its place is emerging a larger state machine, penny-pinching yet more profligate, carrying higher costs and raising higher taxes to cover them; less inclined to support its financial system, more inclined to support its army: bigger state, bigger army, smaller finance.

Source > James Meadway at his substack

The Anti*Capitalist Resistance Editorial Board may not always agree with all of the content we repost but feel it is important to give left and progressive voices a platform and develop a space for comradely debate and disagreement.

Art Book Review Books Campism Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review Fourth International France Gaza History Imperialism Iran Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants Palestine pandemic Police Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War