A mediaeval three-panel painting by Hieronymus Bosch called The Garden of Earthly Delights forms the backdrop to this film, appearing in most scenes on the back wall behind the actors. Bosch was painting in times when death and disease from wars and the plague were common. Through hundreds of beautifully depicted strange human and animal creatures, he depicts the cycle of life and death, as well as the certainty of hell or heaven. Overall, the picture shows the potential for earthly delight, even sexual pleasure, but the final panel provides the moral message of the terrors of hell if you transgress religious rules.

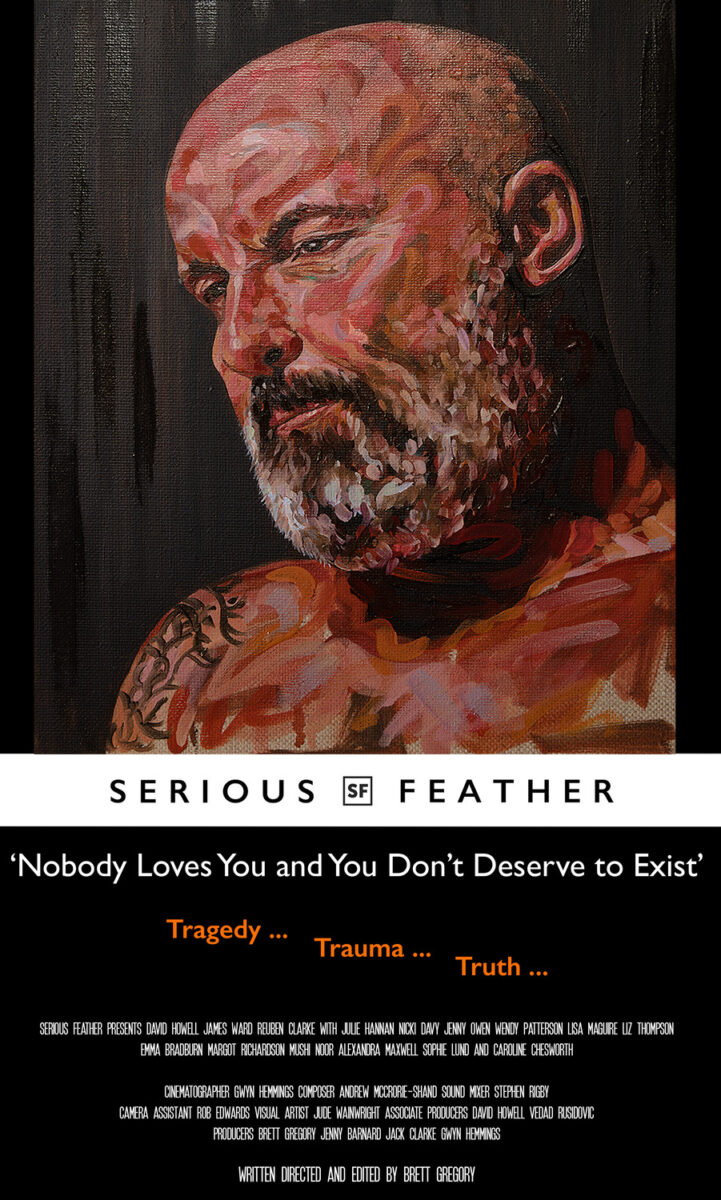

Along with this recurring image, the film is also held together by a moving but melancholy soundtrack. A quote from Borges, which is from a short story where people are brought into the world through dreams, prefaces the film. It suggests how people can feel that their appearance in the world is beyond their control and that their existence has no agency.

We follow the sad story of Jack, born into a working class family. He never really knows his birth father, and he suffers abuse from various stepfathers. His mother shows him little love. To a degree, he escapes from the misery of his home and the narrow bleakness of his estate by reading and learning. His peers on the estate react negatively to his desire for education. The university provides a hedonistic interlude. Later, he becomes a teacher, appreciated by his students but rejected by his college management for not fitting in with the demands of Ofsted. COVID kills one of his closest friends. There are allusions to a failed love affair and then a descent into alcoholic and drug-fuelled abuse. We see him leave his flat, and the film ends with him crawling up a hill in the Pennines, pulling an empty suitcase. You feel he is a lost soul with no future.

There is little conventional plot or narrative but a series of monologues by Jack at three different stages of his life—under Thatcher in the 80s, then the Major Government, and finally Johnson and the pandemic in 2020. So his personal alienation is anchored in the social alienation generated by three anti-working-class governments. You can see the link between the powers of mediaeval times constraining our behaviour and the capitalist forces Marx identified as commodifying all our lives on the altar of exploitation. Manchester and the North are correctly shown as suffering some of the worst effects of austerity and neo-liberalism.

Three different actors play Jack, and the standout performance for me is the pre-teen boy who captures all the frustration he experiences with his family situation but at the same time shows the determination to escape through his love of books. Here the monologue takes place as the young Jack walks his dog—who we never see, another way of showing his isolation—on the hills outside Manchester. Another long monologue is delivered while walking through run-down, poor areas of Manchester. These monologues are interspersed with often poetic reflections by the narrator as images of Manchester are shown. The reality of de-industrialisation and unemployment is communicated.

Alternating with Jack’s monologues are ones delivered by women. His sister, the sixth-form teacher, his college head of department, a religious fanatic (a link back to the painting), and his neighbour, who is angry about the noise Some of these show Jack’s qualities and potential; his teacher enthuses about his pithy but astute reactions to texts. Others show the world bearing down on him. The college’s line manager scolds him for teaching in a way that doesn’t follow Ofsted’s rules and gives his students unrealistic ideas that take their minds off how important it is to train them for jobs.

Visually, the film reinforces the bleakness, anger, and despair of Jack’s life. We are enclosed in bare, sparsely furnished rooms. Even the outdoor scenes on the moors are cold and windy, not sunny or warm. Some allude to other aspects of his story that are never fully explored in the film—we see Jack printing leaflets about a missing girl, or is it him—one of the leaflets appears to bear his face. The leaflets reappear in several scenes. Other images that come to mind are Jack punching a punching bag or crawling up the hill with the suitcase.

It would be dishonest to say the film is an easy watch. I suppose that is the point; real desperation is maybe better conveyed if we experience the discomfort and darkness as we watch. We never see two people interacting. It is a series of monologues by or about Jack. Although there is a basic chronology, it does not have a conventional beginning, middle, and end. There are no climatic moments or plot twists. All the monologues are performed really well and are utterly credible. The soundtrack, the Bosch images, as well as the voicemail messages of his estranged grandmother, help provide coherence to Jack’s story. The repeated references to the glowing stars stuck on his bedroom ceiling draw the monologues together too and point to his failed hopes.

Brett Gregory worked on this film for six years, and it was self-funded. He did not receive the support of TV networks like Channel 4 or the BBC. It has received 55 awards internationally since it came out in May 2022. It is now available on Amazon Prime for about £4 rent so it will be able to reach a wider audience. However, the director will make it available free for local community screenings.

A Ken Loach film it is not, although who is to say this film is not as effective as Ken’s at showing working class alienation? This film is a brave attempt to go beyond the limits of social realist forms of conveying working class experience. It is certainly worth the effort to see something quite different.

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Event Video Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Global Police State History Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party London Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants NATO Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War