The film begins with a long take of a woman carrying her baby through the night and wind towards a beach and the sea.

A mother who kills her baby is one of the most extreme and difficult acts for us to understand. Parents, and women in particular, will do anything to care for and safeguard their babies. Behaviour in the non-human animal world has many examples of this instinct. Women have often risked or lost their lives to save their babies. So a serious film that deals with what is a profoundly unnatural act warrants our attention. Better still, through its almost forensic detail, it shows how such rare, violent events can be largely but never entirely explained through a materialist, analytical framework of feminism, class, psychology, and racism.

The story is told through the eyes of two women, both of whom are from black African families from the former French colonies. Rama is a young academic and successful novelist who is interested in the trial of Laurence Coly for child murder that is taking place in St. Omer. She wants to write about it. In an early scene, we see Rama discussing Marguerite Duras’s work in relation to film clips of women humiliated and shamed at the end of the Second World War for associating with the German occupier.

We are also introduced to Rama’s partner and her own Senegalese family. Her mother needs care, and her father has already passed away. We sense that the relationship with her mother has not been smooth. His sister asks, but she is too busy to take Mum to a medical appointment.

We only see Laurence, who has grown up in France in a Senegalese immigrant family, in the courtroom. Indeed, most of the film takes place there. Unlike in Britain, the presiding judge seems to lead much more of the trial, taking us through the details of the case.

We learn that she was a good student and wanted to study. In later testimony, she says she wanted to become a philosopher like the great ones she was reading. Following an estrangement from her parents, which also involves her father refusing to support her studies, she moves in with a much older white Frenchman. She loves him but gradually realises that he will never leave his wife and wants no public recognition of their relationship. Although nonviolent, this setup has a slave/colonial feel to it. Already isolated and without friends, she becomes even more of a prisoner in her apartment. According to her testimony, she remains there for six months after the baby is born, marooned there, using the internet for baby care advice.

Apart from her testimony, we hear the older partner and one of her teachers speak. Although he now has some regrets and “blames himself,” he displays zero awareness of how his behaviour up until now had been so damaging to Laurence. If we believe him, he did not reject the baby and financially supported her. The teacher portrays Laurence as some sort of fantasist for wanting to become a philosopher and study someone like Wittgenstein. In one of the standout moments, this teacher suggests she should have chosen a thinker closer to her culture and background! Ironically, the French state is very fixated on an assimilationist rather than a multi-cultural approach to official race relations.

Unlike the Hollywood courtroom drama, which is a popular film genre, there are no dramatic twists in cross examinations, no witness breakdowns, and no guilty confessions. It is almost like a play in the theatre, with very long static scenes. The narrative is not centred around the star lawyer. We are not treated to regular flashbacks to the events of the crime or some external search to find vital evidence. There is no real resolution or happy ending.

But it works because of the interplay between Rama’s life (we discover she herself is pregnant) and the eloquence and clarity of the court scenes where the judge and the defence lawyer try to come to an understanding of why Laurence acted as she did.

The closing speech by the defence lawyer is the absolute highpoint, pleading with the court to go beyond the narrow legal rules to look at a just settlement of medical and social support for Laurence. She brilliantly debunks the “sorcery” arguments that the media or other specialists use to explain her client’s actions. Sorcery claims are external signs of deeper problems. Laurence had pleaded not guilty on the basis of following the “voices” of sorcery. The lawyer includes a fascinating reference to “chimera” cells linking mothers and their babies. Definitely it is one of those scenes I would love to see again

Adding Rama’s story as a link or way into the drama of Laurence prevents the formal austerity of the court scenes from becoming too dry or overwhelming. You get a sense at the end that Rama—who may or may not write about Laurence—has learned a lot through Laurence’s experience. The accused woman’s mesmerising performance is tremendous in expressing the complexities of a psychically tortured woman. There is no real resolution to her character because the film makes no claim to fully comprehending what drives a woman to do what she did.

However, like Euripdes, the classical Greek playwright, who wrote about Medea killing the sons she had with Jason after he betrayed her, Alice Diop, the film’s director, wanted to show the context and psychological reasons for such actions. One of the final scenes in the film shows Rama watching scenes from Pasolini’s version of the Medea myth, starring Maria Callas.

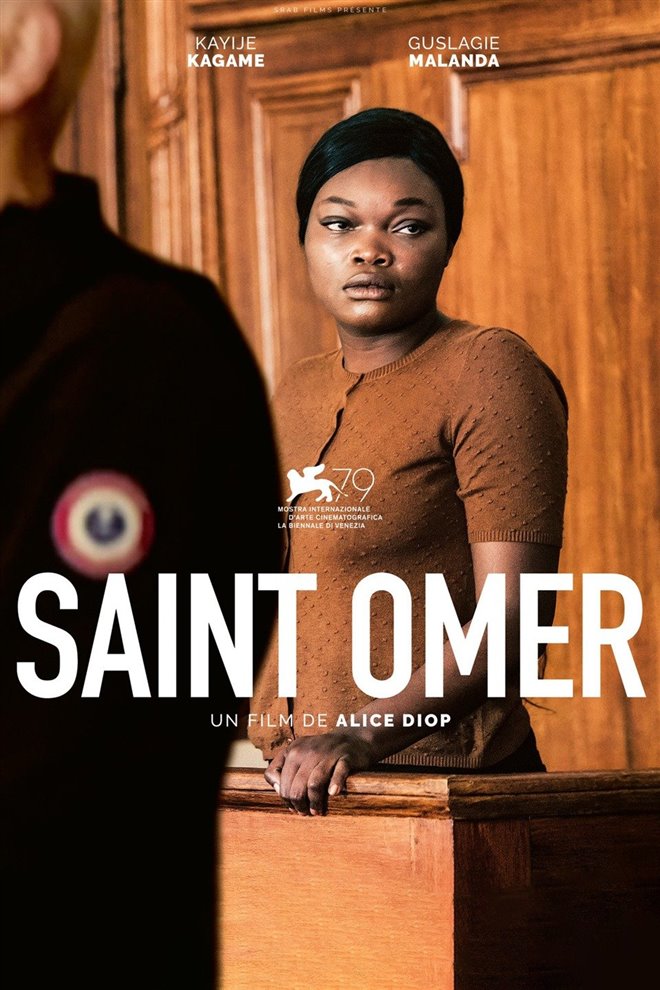

St. Omer is inspired by the real-life case of Fabienne Kabou, who, like Laurence, claimed sorcery had pushed her to kill her baby and whose 2015 trial was attended by Diop. It won best film at the Venice Film Festival this year.

Alice Diop told Variety,

“I wanted to recreate my experience of listening to another woman’s story while interrogating myself, facing my own difficult truths. The narrative had to trace a series of emotional states that can lead to catharsis. It’s like accelerated psychotherapy.”

Fabienne Kabou’s sentence of twenty years in prison for killing her daughter was reduced on appeal to fifteen.

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Event Video Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Global Police State History Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party London Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants NATO Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War