Seychelles is, according to polls, still, for the third year running, the most romantic travel destination in the world. There are white powder beaches in which turtles lay eggs, azure-clean seas, and intense green vegetation that includes mango trees, around which the giant fruit bats swoop at dawn and dusk. Away from the super-expensive island resorts, there is even a network of bed and breakfast establishments surrounded by friendly, helpful people who seem delighted to see you.

But it is not all perfect; beneath the waves are often rocks, sometimes spiny sea urchins, and at 1, 2, 3, and 4 in the morning it is dog o’clock, with the noise of barking and yapping breaking through the windows that you must keep open if you are to avoid using the air conditioning. If you dig deeper, you will learn something about the deep political divisions. I travelled around for three weeks, barely enough to scratch the surface, not enough for the kind of analysis that needs to be developed by those who have lived through the last half century here, but these notes are reflections on what I read, saw, and heard.

Introduction

The Republic of Seychelles gained independence from Britain in 1976. A year later, on 5 June 1977, Albert René at the head of the Socialist Peoples United Party, seized power in what was proclaimed, and is still remembered by some activists here today, as a ‘socialist revolution’ in Africa. René quickly dismantled the opposition, and ran a one-party state from 1979 until 1993. He then opened things up for multi-party elections, which he won that year, 1993, and in 1998 and 2001.

René’s anointed successors held onto power after he stepped down in 2004, winning elections for what became the Seychelles People’s Progressive Front and then People’s Front in 2006, 2011 and 2015, apparent clear endorsement of the course of the ‘revolution’. This until 26 October 2020, when, in the midst of the Covid crisis, and disarray and defections from the ruling party, the current neoliberal coalition, Linyon Demokratik Seselwa, LDS, took power, with Anglican priest Wavel Ramkalawan as President.

What remains of the Socialist People’s United Party, Seychelles People’s Progressive Front, and People’s Front is still present in the 35-member National Assembly as United Seychelles, with 10 seats, but the apparatus of the old regime is under investigation for corruption, disappearances, and murder. Over a hundred testimonies are now being heard by the Truth, Reconciliation and National Unity Commission.

The revolutionary events of 1977 are now officially and mostly popularly regarded as a coup followed by a dictatorship. It is difficult to disentangle what was progressive from what was reactionary about René’s regime and to find spaces of genuine open resistance. A taxi driver told us that the new government is doing well but that the opposition is always creating trouble and is now objecting to the plan to raise the retirement age from 63 to 65.

Versions of the present I

The daily newspaper Seychelles Nation, the 16-page A5-size mouthpiece of the current LDS regime published on the main island of Mahé, carries under the title the words, in capital letters, no accents, “LIBERTE, EGALITE, FRATERNITE.” About 3,500 copies of the paper are distributed to government departments and state outlets, and a few are sold in shops. The November 15 issue carries the main headline, “Air Seychelles out of insolvency process,” with the paper reporting the conclusion of a thirteen-month company reorganisation that will ensure “financial stability.” Just below that, still on the front page, is good news about funding for “capital projects” in the 2023 budget. There are reports inside the paper on an agreement brokered at COP27 for a solar cooling and cold storage project off the island of La Digue and a “national entrepreneurship strategy.”

There are also reports on a deal with Cable and Wireless, with the hook that live sports will be offered in English. The paper is almost entirely in English, with one small item in French about crowds gathering to watch masses of crabs and tuna on Eden Island and another about a special mass held in one of the Catholic churches on Grand Anse in Mahé (the country is over 75% Catholic) to celebrate International Men’s Day.

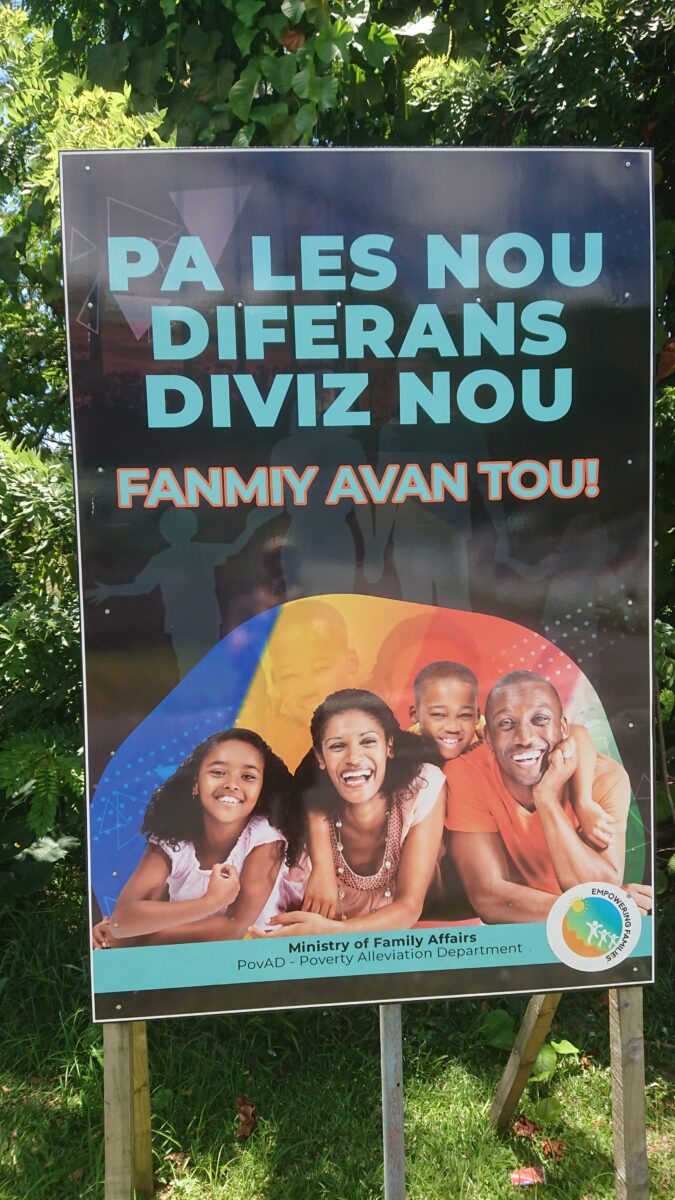

There is a small item in Seychellois about finance debates in the National Assembly. Seychellois, the local form of Creole, is the official language of the National Assembly and was promoted in schools; it is the language used by most of the population, more widely than English or French, but there is now a backlash against this, which the Linyon Demokratik Seselwa, despite its Creole name, is willing to pander to. The leisure page, with a crossword, wordsearch, and cartoon, is in Seychellois, and the rest of the paper is pretty well taken up with job and commercial tender advertisements.

The sports page, in English, reports on hockey and on Everton and Manchester City as winners of the Seychelles Schools’ Premier League. “Everton” and “Manchester City” here are actually Pointe Larue and Belonie; La Digue island is “Norwich,” Praslin island is “Brighton and Hove Albion,” and Anse Boileau is “West Ham.” Among the classified advertisements is one for the Gerard Hoarau Foundation about the Annual Anniversary memorial service at St. Joseph’s Church at Anse Royale, “an invitation to all Seychellois to participate in this moment of spiritual reflection and prayer in thanking God for a patriotic son of Seychelles.”

Reconciliation and National Unity

This is a work of reconstruction, something that one of our hosts describes as the return of capitalism to the island now that “the communists have gone, thank God!” This last thanks is said while crossing himself. For this guy and other members of his family that we met in different parts of the main island, the teaching of Seychellois was nonsense, and the communists were at the source of all that is now bad on the island. But as you listen more closely, contradictions emerge, and we learn that while he was away from Seychelles, the government stole some of his land—he waved his arms across a mountainside to show us what had once belonged to him—and refused to repair the roads, citing “jealousy,” according to his wife.

Anything and everything, ranging from noise and theft to drug abuse and benefit scroungers, is laid at the door of the communists, and this guy, who was in the army when René seized power and fled for some years to be part of the very large exile Seychellois community, is quick to remind us of the London 1985 assassination of Gerard Hoarau, who led the Mouvement Pour La Resistance, by the regime, “probably by Russian hitmen,” he says. It’s possible; it’s true that René had a security apparatus and financial support from the Soviet Union, East Germany, and North Korea. Cuba provided “advisors” embedded in the police force.

Again, as with the West, it seems like support for the “socialist” regime from the Stalinist bloc was based on geopolitical calculation with little regard for what was actually going on inside the country. Nationalisations were carried out sometimes to settle scores rather than as part of a democratically agreed plan of development, and disappearances were engineered to deal with individual troublemakers and, it is true, some sustained military attempts to depose the regime.

Mercenaries

These attempts included the farcical “Mad Mike” Hoare adventure in 1981, which was organised by the opposition in South Africa. Mercenaries arrived at the International Airport and almost succeeded in getting the hidden guns through security. Their bad luck was that the guy in front of them in the queue was caught smuggling fruit into the country, and so customs police decided to search all the other customers; there was a shootout, and the mercenaries were confined to the airport. René then brokered a deal to release them and, after negotiations with the South African government, got agreement that the apartheid regime would crack down on the Seychellois opposition and pay financial compensation to the Seychelles.

Here is another indication of the paradoxes at the heart of the regime that give lie to claims that it really was “socialist” or “communist.” Apart from some military and police support from “friendly” states willing to make the most of a regime that appeared to be breaking from the West, most of the internal and external security – including surveillance of the opposition at home and abroad – was also run by mercenaries; a private security firm, Priority Investigations. This outfit was run by a mercenary, Ian Withers, who was appointed National Security advisor and who then described himself as a member of the “Seychelles Security Service.” Withers also ran the “overseas unit” and was hired by René to oversee these matters.

René made little reference to apartheid in South Africa after the 1981 coup attempt against him, and there was always a cautious, shrewd balancing act between different international and regional powers. For example, and this is a significant one, there was no support for the Chagossians after the US and Britain seized the islands—geographically and historically part of the Seychelles, though legally under Mauritius administration—and René did nothing to speak out for these people exiled from their own archipelago.

René did not significantly disturb the Brits, the old colonial power, even while he began using French terms to describe aspects of the new state administration—mere symbolic shows of defiance—or the United States; the listening base that the US maintained on Mahé was never put in question—it provided money and employment—and it was the US that finally pulled the plugs on that after 1989, which was also a watershed moment for policy inside the Seychelles.

Now the new government has just brokered a deal with Thai Union which operates a massive tuna processing plant in Victoria, the capital. The factory runs 24/7, with clattering and rumbling echoing up and around the hills, and this operation will now increase with the expansion of the plant over the next few years. The three main economic drivers of the Seychelles economy are tourism, tuna, and offshore financial services, all three sectors of which René explicitly and deliberately kept in private hands while using some resources to fund education and welfare, which are still free but are under threat from privatisation.

Versions of the present II

The Seychelles Independent, a weekly newspaper, is now the voice of the United Seychelles. Its website is pretty inert, and the paper is difficult to find. Below the title is the legend “Sesel avan tou,” though all of the paper is in English. I picked up a 9 November copy at a supermarket in Anse Boileau, where there had been a recent United Seychelles rally, an event reported in the paper. It is impossible to know how many copies of the paper are printed and sold. The front page of the 12-page A4 paper featured three stories about LDS mismanagement and corruption, an important pitch now made by United Seychelles in the face of the Truth, Reconciliation, and National Unity Commission, TRNUC, testimonies and investigations aimed primarily at the party.

The Nation takes a different spin on the LDS 2023 capital investment budget, claiming that there is a lack of attention to the “ordinary citizens who bore the burden” for the economic sacrifices that are being made. These stories run over the first four pages, and then there are two stories on page 5 that run in stark contrast to each other, stories that point to some contradiction in the United Seychelles’ attempt to wrongfoot the government. The main story on page 5 with a full-colour photo of a rally at Anse Boileau is topped by the headline “Red revival is a reality!”

The United Seychelles local rally on the west coast of Mahé shows, the story claims, that United Seychelles is “still a force to be reckoned with and even that it is well on the road to recovery.” ‘Despite the TRNUC’s revelations and accusations of corruption, it continues, “the 28,000 plus followers saw no reason to change their allegiance.” Impressive though the photo is, in no way are there 28,000 people there, and it is improbable, to say the least, that such a number out of a total Seychelles population of under 100,000 people gathered at the beachside that afternoon.

The story also complains that the Seychelles Public Transport Corporation refused to hire out their buses to take supporters to the rally, so the numbers hinted at in Anse Boileau are even more questionable. Rare graffiti was around in Anse Boileau: an environmental “Save Our Seas” slogan echoing an ecological youth movement developing in Mauritius and one proclaiming that “there is no political solution,” which hints at political disaffection rather than engagement.

On the same page is the second story, and it is a surprise to read the headline for that, which is “Health Ministry should consider outsourcing ambulance services,” basically a call for privatisation. The following pages complain about increased powers given to the police and string together some quibbles about proposals mooted at a teachers’ symposium; “Teachers feel inundated with paperwork,” says a little box highlight in the middle of the article.

Two pages are taken up with an interview with Ralph Volcere about the shortcomings of the LDS proposed budget. According to the first paragraph, this is the first of a two-part series. The article is again supported by the argument that all of the government’s claimed economic success is due to the “poor working people of the country.” Ralph Volcere is the editor of the paper. There is a reprint of a rather neutral article about negotiations between Britain and Mauritius over the future of the Chagos Islands.

The Volcere “interview” is followed by a downright weird, unsigned piece that looks like it is designed as internal political education for party members. It is titled “Do we have the political will to tackle our problems?” and includes ruminations on the nature of the human being as being “the focal point of all forms of motion of matter.” In a garbled version of good old Soviet “socialist man” pegagogy, the piece contrasts individual competitiveness in present society with the nature of the human being as “a subject of historical creativity.” The final paragraph speaks of “the spiritual nucleus of the structure of the personality,” and this puzzling article—some indication of the political heritage and line of the paper—concludes with the enigmatic sentence “What is it all about?” Indeed.

Albert René

It does seem that if René had not seized power in what was actually more of a coup than a revolution in 1977, the first elected President James Mancham, would himself have shut down opposition parties and ruled through his Seychelles Democratic Party, SDP. René moved quickly while Mancham was in London at a Commonwealth Heads of Government meeting, where he was invited to speak. However, as soon as the Socialist People’s United Party took power, the invitation was taken away.

That rapid recognition of the new regime was a sign that, though Mancham was the preferred choice by the old colonial powers, Britain and the United States reckoned they could live with René. In fact, both Mancham and René, who both trained as barristers in London, had been groomed as future leaders before independence, with paid visits to London and the US. In some respects, with the geopolitical location of the Seychelles more important than internal administration, this hedging of bets in René’s favour was the safe and rational option.

René clearly had support in the country, and attempts to depose the new “socialist” regime would, in the view of imperial and regional powers, cause more chaos and uncertainty than was worth it, but the problem was that in no way was the Socialist People’s United Party a mass party, even less so a democratically structured organisation, and the coup was carried out by tens of people, most of whom had no idea what they were involved in when it happened. That contradiction—a single individual attempting to construct a socialist alternative in a country of less than 100,000 people in a 115-island archipelago in the middle of the Indian Ocean—haunted the regime from 1977 on.

It is easy to reduce what happened in 1977 and since to the personality of the single individual at the head of the regime. There is a thorough and thoroughly partisan account of what happened in the just-published book by Ashton Robinson, René and Postcolonial Seychelles: An African Chameleon in the Indian Ocean, which does exactly that. Robinson writes for the neoliberal Lowy Institute, and it is clear where he stands in his reports on the island.

You will learn from Robinson’s hatchet job that Albert René was a thoroughly bad sort who treated his family badly, duped the Church into providing sponsorship to train as a priest, dropped out and trained as a barrister, and then plotted a path to power with a ruthless determination to drive out the West and let in the reds. All of the errors of the regime are reduced to deliberate behind-the-scenes machinations by René, something that obscures the very constellation of social forces that made 1977 possible.

For example, the Catholic Church was and is a powerful cultural and potentially powerful political force in the Seychelles, but one of the dominant orders—the one that René was initially sent to train with in Switzerland as a novitiate priest—was the Order of Friars Minor Capuchin. The Capuchins were not at the forefront of liberation theology, but there were plenty of local priests in the Seychelles in the order who were sympathetic to it, and this, according to Robinson, gave encouragement and licence for René to engage in the coup. The Church was unaware of the coup’s impending arrival and did not support it, but it also did not condemn it, as it could have done in other circumstances. In Robinson’s book, the reds in the church effectively egged on the evil René.

Robinson also noted the British Callaghan government’s determination in the 1970s to implement its “East of Suez” policy, divesting itself of the old colonies. Joan Lestor and Judith Hart, among others, are blamed for a lack of oversight for what was about to happen in the Seychelles after independence. This was disastrous for Robinson, and so the British Foreign Office bears some responsibility for letting René in. There may well be some truth in this specific play of circumstances, but the political slant Robinson gives it is quite reactionary.

Slavery

A supporter of René’s regime said that the revolution in 1977 was, for all of the problems, and it was by no means perfect, “necessary.” It was only with the land reforms that were promised and then delivered that slavery in the Seychelles was finally ended. Up to that point, the “moitié” system that effectively prolonged slavery after its formal abolition gave former slaves only the right to “half” of their freedom and kept control of the land in Seychelles in the hands of 9% of the population. This was definitively ended by René, much to the anger of many of the old landowners and their descendants who provided financial support to the different iterations of the “opposition.”

Slavery and the legacy of particular forms of patriarchal oppression that issued from it structured the Seychelles as a newly independent country in 1976 and set particular kinds of tasks for a progressive regime. This history set in place specific kinds of intersections between class, “race,” and gender. This was a revolution in Africa—the bulk of the Seychelles population is black, the descendants of slaves—with René and his close circle of supporters intent, in the early years, on reorienting the country away from Europe to Africa.

René had close links with Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, who ran his own “socialist” one-party state before the revolution, and Tanzanian troops were present at key points in the island during the coup. Later on, relations with Tanzania cooled. A leader of the then-radical Mouvement Militant Mauricien, Paul Bérenger, was photographed with René on the island very soon after the coup—he was apparently there at that time by chance, it was claimed—though links with the MMM were not maintained for long after the revolution. However, independence as an African nation was crucial to René, and one supporter said that it was only with the 1977 revolution that the Seychellois were able to begin constituting themselves as an independent nation.

Even the most hostile accounts of the René regime, with Ashton Robinson’s book as a prime example, had to acknowledge that though there was a legacy of racism from slavery, this was actually quite minimal in the Seychelles, even remarkably in a country that was governed by a self-proclaimed African liberation movement headed by Albert René, a white man. It was difficult to instrumentalise racism by opponents of the regime, even if one older man we spoke to claimed that the country under the “communists” was taken over by Whites, Russians, and, more recently, Indians who run the supermarkets. The government did and still does take efforts to represent Seychelles as an inclusive family; the faith of the President, an Anglican, and the Vice-President, a Muslim, is of little interest in an overwhelmingly Catholic country where it is the political history that counts.

Women, we were told, formed the active support base of the movement, insofar as it could be said to be a movement, and United Seychelles is in the process of recomposing itself following the 2020 election defeat, including a women’s wing and a youth wing. There are very good detailed accounts of the position of women here by Penda Choppy who is Director of the Creole Culture and Research Institute in the University of Seychelles at Anse Royal (location of one of the best beaches we found in Mahé, by the way) of the forms of family that gave women certain forms of autonomy and power in Seychelles.

The 1994 Termination of Pregnancy Act, which loosened control of reproductive rights, was a blow to the Catholic Church, probably René’s revenge against the Church that had, with the rest of the opposition, effectively blocked his referendum over the ratification of his new constitution two years earlier. Nevertheless, abortion is still illegal in the Seychelles, and there is no publicly visible women’s reproductive rights movement or, for that matter, a visible feminist movement.

Most of the population are descendants of slaves, many of whom had been freed from bondage by anti-slavery activists who impregnated many of the women they left on the island. No European hands were clean during the history of slavery and its aftermath. Women were then forced to take charge of family finances and the care of children, independent and, in some sense, powerful in relation to men, men who were, as a function of slavery and racism, emasculated. That history of women’s power carried through in the allegiance they showed to radical movements, even movements like René’s that were run by men.

A youth wing of the United Seychelles is a difficult, touchy subject, for some of the first public mobilisations against René in 1979 were actually by school and college students protesting against the formation of a National Youth Service and, in hindsight, a disastrous mistake, the closing down of football clubs and the incorporation of sport into the same administrative apparatus as that which was responsible for imposing a two-year spell of national service. The Rovers FC was politicised as a side effect of it being disbanded by the government, and the opposition later on included many former Rovers FC players or officials. The National Youth Service was a typically top-down initiative, designed to bring the nation together, and, predictably, it failed.

Disintegration

One thing is for sure, that ‘socialist’ rule in Seychelles from 1977 to 1993, and for some time after that even while there were multi-party elections, was a form of dictatorship. It was René who called the shots, perhaps, according to Robinson’s book also present during some of the police and army interrogations of arrested opponents, and it was René who saw which way the wind was blowing after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Just as he had been able to balance between East and West up to then, playing Soviet against US support while developing an offshore banking system that had links with organised crime, after 1989 and the effective end of the Soviet bloc, he put all his bets on the West again, and that required shifts in policy and significant shifts in forms of rule; now there needed to be elections in order to secure legitimacy from his primary investors. These shifts saw a more explicit emphasis on external capital investment, something he had always anyway courted.

From then on, it was a downward slope towards neoliberalism, first under René and his successors, and now under the LDS. The regime came to an end during the COVID pandemic after some missteps, but that situation of intermittent lockdown and closure of the islands — something that badly impacted tourism, of course — cannot be blamed for the final election defeat for Danny Faure, educated at the University of Havana, and from 2016 President as appointed heir of René’s chosen favourite James Michel, who ruled from 2004 to 2016, and successfully fought elections until he stepped down mid-term.

Faure’s gambit was to call for a government of national unity to tackle the crisis, but by that time the opposition was well organised and the ruling party was in tatters. Other contenders for a “national unity” coalition were better placed and more credible. When the left plays this tune of “national unity,” it is usually the right who benefits. One United Seychelles member we spoke with even admitted that it was possible that the party lost power in 2020 because it was not yet in a position to govern after the next election. COVID or not, Faure was going to lose.

Nonetheless, they reminded us that Wavel Ramkalawan, the current president at the head of the coalition, is not suited for power either, with a history of personal and public violence and in his past and broken promises, which include opposition to the army when in opposition and support for increased army presence on the streets now that he is in power.

Endings

One could say, in fact, that the ‘socialist’ revolution of 1977 was, with added progressive land reform, education provision and welfare benefits, not so much a proletarian revolution of the kind that Marxists looked to in order to bring an end to capitalism as a very radical bourgeois revolution. That is exactly what the Stalinist states René traded with would also prefer. Despite the claims by some of the old United Seychelles cadre – a very small group of people at the head of an apparatus and then electoral machine – there was very limited collectivisation of production and, instead, the concentration of economic and political power in the hands of a new elite at the helm of the state.

From that kind of bourgeois revolution, one would expect, if there was no active democratic socialist movement, a degeneration, bureaucratisation and then exactly the kind of abuse and corruption that the Truth, Reconciliation, and National Unity Commission—a commission that was referred to as a “circus” by one United Seychelles member—is honing in on. A woman described her sense of fear when she heard reports of the Commission and remembered being watched by men she now thinks could have been from internal security. This circus, if that is what it is, has material effects on the memories of those who lived through the last half century here.

This was, at first sight, a ‘socialism’ betrayed, mislaid and unmade, this time almost all at once, unravelled by the concentration of power in a few hands right from the start, impossible to carry through without a mass movement and without any democratic accountability. That pattern seems to be replicated now in the “United Seychelles” movement, even if there are claims that many local branches are led by women, and it is an open question as to whether a new opposition that is not trapped in the false choice of having to decide between or balance between different international blocs – East or West – can develop inside United Seychelles or must begin from scratch outside it.

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Event Video Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Global Police State History Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party London Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants NATO Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War

Many thanks to a friend here: ‘two small amendments – René’s founding Party was called the Seychelles People’s United Party – not Socialist People’s… Secondly, The Independent is not the mouthpiece of the US. Rather, it is as it says, an independent newspaper ran by Ralph Volcère, who very often severely criticizes the US – but is mostly interested in criticizing the current government, probably as a residue of his falling out with them several years ago when their alliance failed.’

There is an updated corrected version of this report here: https://fiimg.com/2022/12/15/the-republic-of-seychelles/