One of the biggest non-surprises is that the British economy fell into recession. It is unsurprising because all government and Bank of England policies worked to get us here. In fact, it has been evident that they have been trying to create a recession for some time. Perhaps they figured if the economy fell into one, any growth would be attributed to the economic success of Prime Minister Rishi Sunak.

That’s the only explanation I can find for economic policy prescriptions that barely pretend to restore growth to the British economy. Somehow, the beautiful contradictions in Sunak’s 5 Policy Pledges (that sought to restore economic growth to a stagnant Britain and lower inflation using rising interest rates and supply-side economics) were missed by the bank economists appearing on the mainstream media supporting the Tory agenda.

The problem for Rishi Sunak, Jeremy Hunt (the Chancellor of the Exchequer) and the Bank of England is that their tactics were geared towards slowing an overheating economy rather than enabling growth. For instance, the Bank of England kept raising interest rates; in August 2023, they reached 5.25% (and have remained at that level). Growth was evident coming out of the pandemic (or we’d be in even worse shape), but nothing indicates overheating. The British economy has been stagnant. The last thing you want to encourage growth when an economy is stagnant is to raise interest rates!

The Fall into Recession

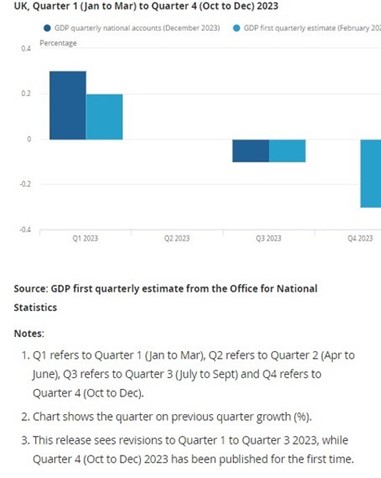

If we look at the GDP data from the Office of National Statistics just released this week, we can see the quarterly estimates of real GDP for 2023:

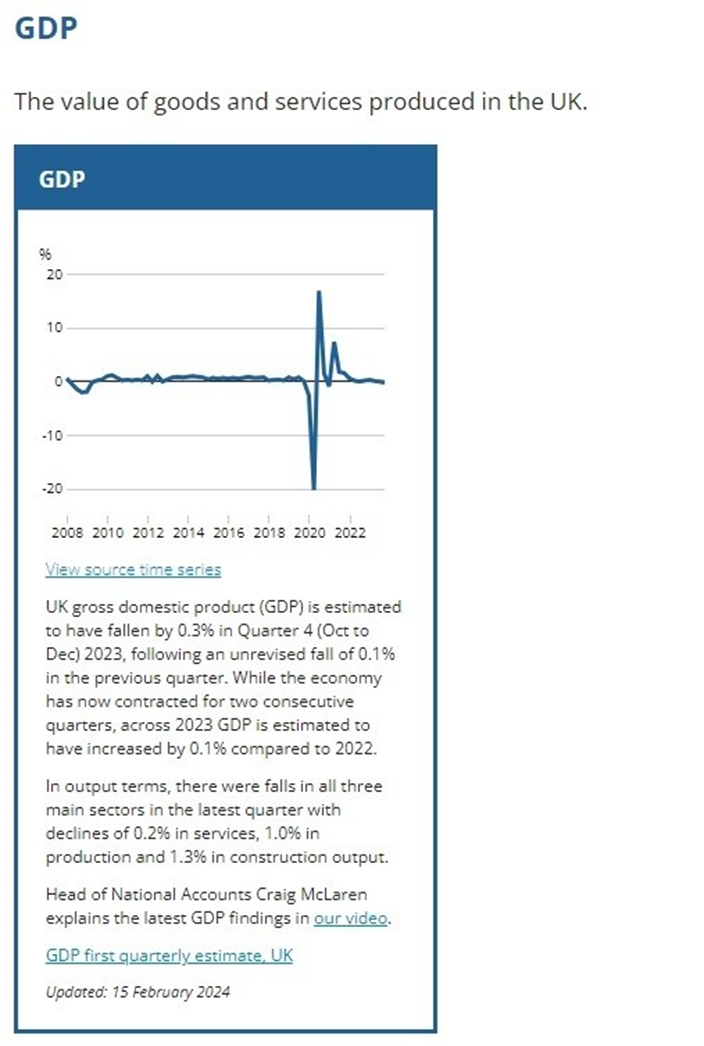

A far more exciting picture emerges if you look at National Accounts, which examine GDP growth over time and demand; these are from 2022, but the picture is clear. We can see how stagnant the British economy is since 2008. We can see the 2007-8 recession (made much worse by government economic policies) with a slight recovery and then stagnation again.

The significant fall is around the pandemic; the economy rises and then starts to collapse back into stagnation before it dips below stagnation and into recession. It is small compared to the 2007-8 recession, but this is where we are at.

Let’s start with demand: this is a measure of demand for produced output by consumers (Retails Sales Index) and Business Investment (for intermediate goods and services) from 2008 to 2024. Demand for consumer goods is constrained for a while; then there is a pandemic and a rebound, and we can see it falling. The main element that has impacted the quarterly and monthly fall in GDP is decreased consumer spending.

So, we have the 2007-8 “great recession”; the ConDem government began in 2010, and in 2015, the Tories under Cameron secured an outright majority. The Brexit referendum was in 2016, and Cameron resigned when Brexit won. After, Teresa May was elected leader of the Tories. Boris Johnson won a General Election in 2019 with a massive majority. Then we have the pandemic; Johnson is thrown out of power in 2022, and Truss wrecks the economy.

In all of this, neoliberalism and supply-side economics have a lot to answer for… Imagine if they had tried to stimulate demand to create economic growth through direct government job creation. But then they couldn’t destroy the public sector, services and lower government investment, but even for them, is doing so worth creating a stagnant economy based on ideological idiocy? Apparently so.

And here is GDP from 2008-2024 (it was just updated on the 14th of February, 2024):

Why do rising interest rates counteract economic growth?

High interest rates impact several things: 1) businesses borrowing for production have to pay more interest on money borrowed (this significantly impacts small and medium-sized businesses dependent on borrowing, including retail); 2) consumer borrowing costs rise; this significantly impacts those reliant on credit cards as interest on borrowing has increased; they will cut back spending; 3) mortgage costs rise due to rising interest rates; these mortgage costs (irrespective of whether your landlord has a mortgage) have been passed to private renters. So, we see rising rents continuing as house prices fall.

“HOUSING: HOUSE PRICES FALL WHILE PRIVATE RENTS CONTINUE TO SEE RECORD RISES

Average UK house prices are estimated to have fallen 1.4% in the year to December 2023 (provisional estimate). This is up from a decrease of 2.3% in the 12 months to November 2023 (revised estimate).

Average UK house prices are estimated to have fallen 1.4% in the year to December 2023 (provisional estimate). This is up from a decrease of 2.3% in the 12 months to November 2023 (revised estimate).

Private rental prices continued to grow at a record high rate in the UK, rising by 6.2% (provisional estimate) in the year to January 2024, unchanged for the second consecutive month. This remains the highest annual percentage change since this UK data series began in January 2016.”

Given the cost-of-living crisis, if people have credit cards and cannot pay immediately, this will cause them to cut spending. Also, if they have savings, and there is no indication of incomes rising, they will save money rather than spend it. While the interest rate increases were belatedly (compared to credit borrowing costs) passed onto consumers, you can earn interest.

But this is irrelevant for those in low-wage jobs dependent on benefits as they live paycheque to paycheque. High-interest rates also impact those getting mortgages (or renewing mortgages, or taking out a second mortgage) and buying expensive items like cars as borrowing is more expensive.

Simply looking at GDP per quarter often does not provide enough information as it doesn’t necessarily explain what factors existed over time that led to where you are. The problem of examining quarterly data (or, for that matter, monthly data) is that it focuses on short-term factors, and the issues that feed into these results do not examine why these occur.

This focus on short-termism also obfuscates the structural problems in the economy and what may be more appropriate solutions to the economic situation. This is why you get reporting from the BBC blaming the fall into recession on consumers spending less, children being out of school, and junior doctors’ strikes – these are not the structural reasons for economic stagnation or the fall into recession. For that, we need to look deeper into the economy itself.

Inflation and the cost-of-living crisis

The Office of National Statistics (ONS) data on GDP discussing the recession talks about decreases in the production of goods and services and about consumer spending falling after deals from Black Friday, but it does not include the cost-of-living crisis. This remains relevant despite inflation stabilising. Rents have continued to rise (despite housing prices falling), and electricity and heating are still high, as are food prices.

Just because inflation has fallen does not mean that we have returned to prices from before the massive increase in inflation, nor has the economy recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Moreover, according to the ONS, “Out of 13 consumer-facing service industries, 10 remain below their pre-coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic levels (February 2020) in December 2023.”

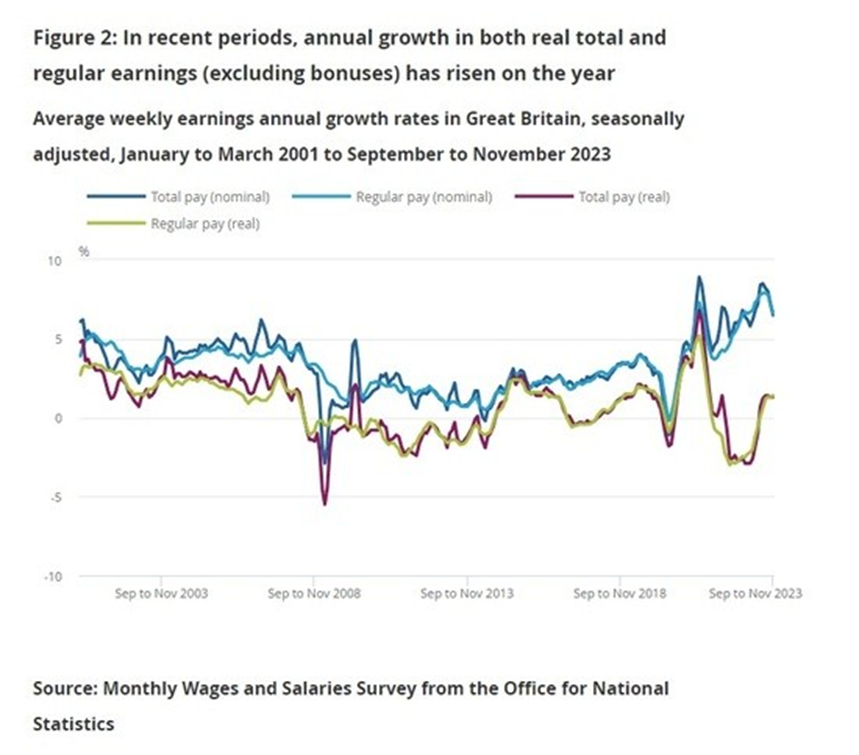

We can see consumer spending has decreased, but why? We need to look at longer-term trends in wage incomes (wages and benefits), employment contracts and the nature of work (so zero-hours contracts where you don’t know the dates and times that you are going to work), which have essentially put younger workers into the reserve army of unemployed with low pay and no benefits like sick days. All these factors will undoubtedly impact consumer spending.

To get an idea about wages and salaries, here is a look at the growth in real, nominal and total weekly wages in Britain. This comes from November 2023 from the ONS Employment and Labour Market series covering the period of 2003 to 2023:

We can see the cost-of-living crisis wrapped up around the CPI services increases, the prices of goods, and the CPI excluding energy, food, alcohol and tobacco from the Office of National Statistics relating to consumer price inflation from January 2024. The only thing missing from this diagram is private rents, which, as mentioned, continue to rise.

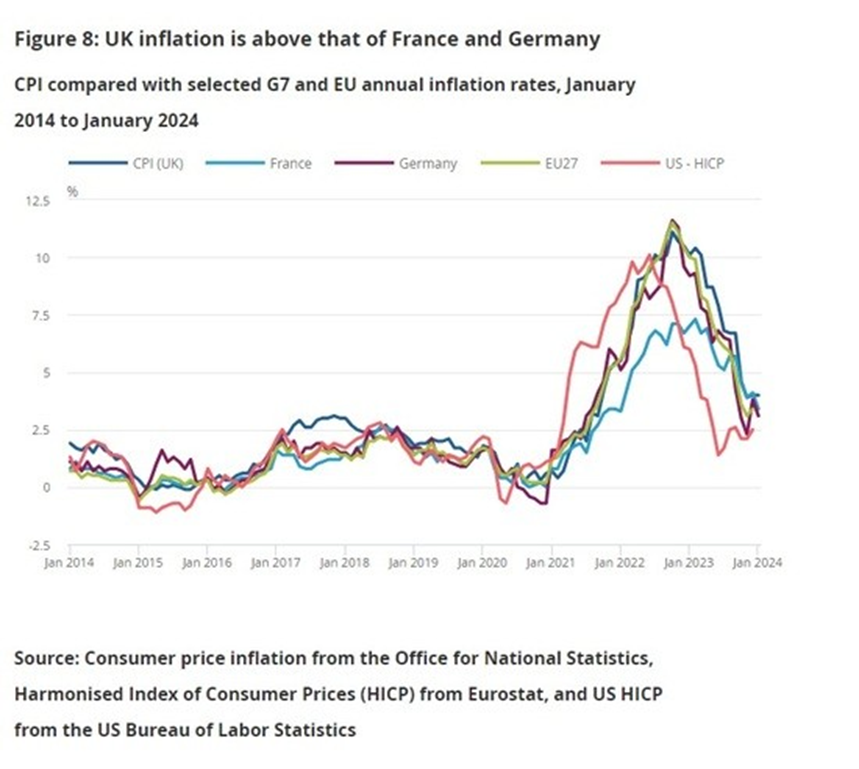

We can see above a graph from January 2024 from the Office of National Statistics, showing CPI inflation in the UK compared with other European countries, the US and the EU27.

We know what caused inflation in the period after the pandemic in Britain:

1) Blocked supply chains:

Broken and blocked supply chains arose due to the pandemic, which meant that the production (supply) of goods adjusted to the demand during the pandemic, and it was not that simple to increase the production of goods and services; there is a time lag to increase production, it is not just turning on a tap. Intermediate production needs to be increased before you can increase final goods production; agricultural production is seasonal. Additionally, production occurs worldwide, and there were blocked supply chains. Prices rose precipitously.

2) Rising prices of fossil fuels and energy (a.k.a. Inflation)

In Britain, this was a three-fold problem:

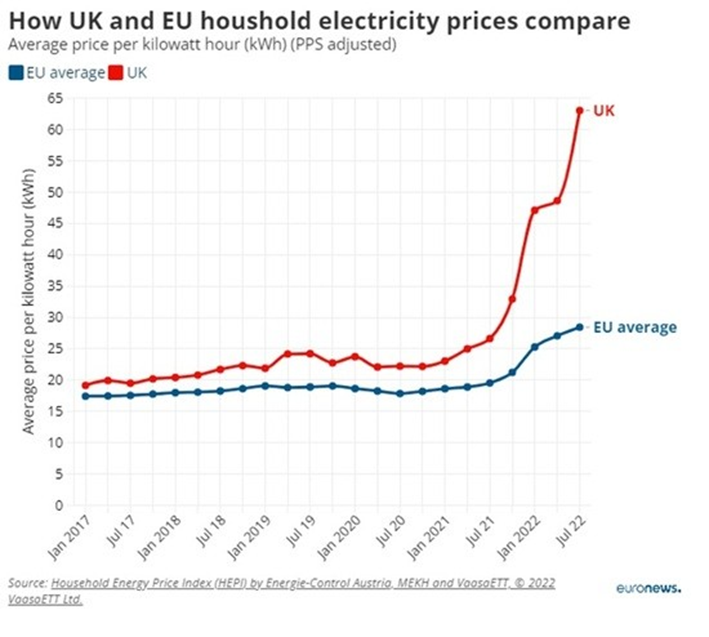

a) private control over energy and fuel prices and the refusal of the government to regulate them; so, while all countries in Europe experienced rising prices of fossil fuels and energy, in countries where energy is owned by the state rather than private companies, energy and fuel prices rose far less (this graph is from 2022, but it is still valid).

Britain provided direct funds to assist consumers cover the rising prices of electricity and heating, but these were not enough to ensure that consumers avoided taking a hit. A small additional amount was provided to disabled people whose energy costs are higher to run medical and mobility machinery and extra laundry; again, this was not enough primarily because many disabled people remained on Legacy Benefits, i.e. the benefits system from before Universal Credit (UC) was introduced as moving onto UC meant lower levels of income support.

Additionally, the £20 weekly uplift to Universal Credit was not given to those remaining on Legacy benefits, which left many disabled people unable to cope with the rising cost of living. There will be a government-forced migration onto Universal Credit, and there is no question that it means lower incomes for disabled people still on Legacy benefits.

Moreover, the British government allowed electricity and energy prices to rise rather than initially regulating revenue earned. The amount companies were allowed to charge the public was capped, and then the money to the energy distributors was supplemented by the British government rather than prohibiting price rises. In May 2022, the government finally introduced the 25% Energy Profits Levy (as a Windfall Tax, but the Tories refused to use that term).

Jeremy Hunt increased this to 35% in January 2023, which should run until 2028. The government then increased support for reinvestment (and investment) in production for the fossil fuel industry at £91.40 out of £100 invested in production in Britain (that this was inconsistent with stated aims towards green and sustainable energy is an understatement). Even with the wealth taxes, distributors made massive profits following a period of lower profits, and they had the gall to complain about the windfall tax!

b) Shift in demand for fuel following the pandemic: During the pandemic, demand for fuel decreased substantially as production slowed, and transport (including car usage and aviation) decreased. Once economies started moving again after there was a supply backlog.

c) The Russian invasion of Ukraine impacted both natural gas and oil production, and distributors took full advantage, raising prices substantially; while production occurs across countries, the war not only impacted fossil fuel production but also food production; while this hit developing economies harder due to a lack of food self-sufficiency and production for export rather than, in many cases, domestic consumption, to some extent, it impacted every country.

3) Rising Prices of Intermediate Goods and Workers’ Consumption Goods (aka Inflation)

There were rising prices of intermediate goods and food: some of this is due to rising transport caused by the high price of oil used in production as an intermediate good in the distribution and transport of other goods. Britain is not food self-sufficient; it gets a lot of food products from the EU and other countries. Global warming impacted output production in Spain and other Mediterranean countries, which increased food prices with goods prioritised for the EU. Britain had to get goods from afar, which increased costs (see transport above).

If inflation is considered a class struggle between capitalists over profits and the working class over wages, we can see that the capitalists have won this round, which still tremendously impacts working-class people.

Brexit and its impact on Britain’s economic crisis

Tempting as it is to just stick Brexit in with the inflationary pressures, the reality is that Brexit seriously impacted the British economy. There was no question Brexit would reduce economic growth. The choice to leave the customs union, single market and VAT area broke supply chains in the trade of goods and services.

This impacted manufacturing (much industrial manufacturing is done across countries in Europe, and Britain’s participation in manufacturing was now slower and more expensive than simply doing this in other countries in the EU). So, Britain lost access to joint European-wide manufacturing production (and, for a time, joint scientific research).

Britain is not food self-sufficient and imports large quantities of food from the EU; agricultural and fishing production are also sold to Europe. So, Britain’s production of food is highly dependent on Europe and leaving the EU has meant increased costs due to paperwork; we still need to follow European rules on food export (that is why the US and Canada demand to accept their hormonal meats resulted in a breakdown in negotiations with the UK as that is forbidden by the EU).

Full custom controls were introduced in 2021 by the EU; this means customs documents must be provided for all imports and exports between the EU and the UK. So from the Commons Library: New Customs Rules for trade with the EU:

“Customs controls ensure duties are paid on goods moving across the border, and goods comply with safety, security, health and environmental requirements. The EU introduced full customs controls from 1 January 2021.

The UK Government has been phasing in border controls for goods imports from the EU from 2021. Customs declarations are now required for all imported goods. Businesses must pre-notify imports of animals, plants, and high-risk food and feed. Certain high-risk animals and plants require health certificates and checks. The planned introduction of the remaining controls – health certification and sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) checks on all agri-food products, physical SPS-checks on EU imports at designated Border Control Posts, and safety and security declarations – has been postponed several times, most recently in September 2023.”

The government of Britain has produced a new Border Operating Model for trade with the EU, which explains the rules and processes of exporting and importing goods with the EU. It is a wonderfully soul-destroying document to slog through if you are not someone wanting to export goods to the EU or import them to Britain.

Neither has Britain opened up sizeable new trade and export markets in other countries and despite being outside of the EU, they are still constrained by EU laws relating to the import and export of goods. So, despite the EU being Britain’s biggest trading partner, all Brexit has done is increase food costs and prices, undermine its financial and manufacturing sector and slow the export and import of goods between the EU and the UK.

The right-wing fantasy of eliminating laws between Britain and the EU (especially human rights law) has not been that easy; the Tories have realised that freeing themselves from the chains of the EU simply is impossible. Moreover, many financial companies in Britain (e.g., insurance and financial services) relocated to Ireland and the Netherlands for their access to the EU. This impacted service production and, contrary to a bizarre belief of a revival of the dominance of the British economy, the UK fell into a recession.

This was expected by anyone who did a basic investigation of the economic impact of Brexit (the MSM cannot be bothered to do that), but it was ignored by the right-wing who supported Brexit; they babbled endlessly at how Britain freed from the chains of Europe would rise to its former glory. While the right wing wished to be free of migration laws in the EU, they forgot that they needed European labour in Britain. Hence, the labour shortage hit the NHS, care sector, and tech sector, and there was a loss of manufacturing, financial services, and pharmaceutical controls to members of the EU.

However, in 2016, a report from the Treasury to Prime Minister David Cameron and Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne projected that Britain would fall into recession if it left the EU with a loss of over 500,000 jobs. This was so over the top no one took it seriously, but it makes interesting reading. The Treasury warned that the shock of a Brexit vote itself could cause a recession.

Perhaps it is only a nightmare, but I recall a reporter asking Jacob Rees Mogg whether the economy would be negatively affected if we left the EU; he said it would be a short blip, but everything would come back stronger. The situation has proven far worse, but no one could have predicted the pandemic… a funny old world we live in.

Mainstream Media Reporting on the Recession

The reporting on the recession was absurd; the BBC opened their article on the recession with the following:

“People spending less, doctors’ strikes and a fall in school attendance dragged the UK into recession at the end of last year, official figures show.

The economy shrank by a larger than expected 0.3% between October and December, after it had already contracted between July and September.”

According to the BBC, the recession is caused by consumers’ decreasing spending, junior doctors being on strike, and fewer children attending school; while this is relevant if you want to look at monthly changes in GDP, it doesn’t tell you much. While mentioned in the ONS report on falling GDP, blaming the recession on these groups of people is absurd. The problem of looking at short-term data is that you don’t get a general picture.

However, if they had bothered to also look at the ONS Cost of Living – Latest Insights that came out on February 14th, they would have benefitted from useful information about housing, with prices falling (1.4% in the year to December 2023), but private rents still increasing.

This data also provides information about the high prices of food and energy and their impact on the majority of the population. Food price inflation is falling, but it is still very high, reducing available income to purchase non-necessary goods and services. The ONS openly states this in several data sets.

“Food: Inflation falls to lowest level since April 2022

Prices of food and non-alcoholic beverages rose by 7.0% in the year to January 2024 according to the latest Consumer Prices Index including owner occupiers’ housing costs (CPIH).

This was the tenth consecutive month of falls in food and non-alcoholic beverage inflation, down from 8.0% in December and a recent high of 19.2% in March 2023, which was the highest annual rate seen for over 45 years.”

Then there was information about energy prices, and 41% of people were still finding it very or somewhat difficult to afford them.

“The survey also revealed that 44% of adults in Great Britain are using less fuel, such as gas or electricity, in their homes because of the rising cost of living.”

This important information could provide insights into cutbacks in consumer spending on non-necessary purchases. But then again, if they did this research, they could not blame Junior Doctor’s strikes and children not going to school for the rising interest rates that have pushed the economy into a recession.

Blaming the victims

The one thing the Tories are good at is pretending everyone else is responsible for their economic disasters; everyone and everything is responsible for their failures except themselves and their policies. In fact, I believe they have made an art of making ridiculous arguments blaming everyone and everything for their failures. We have not even seen the back of Liz Truss and her bizarre beliefs about a left-wing economic consensus scuppering her “brilliant” economic policies; this position appeared in her speech for the Institute for Government in September 2023.

Liz Truss still blames the “left-wing” Economic consensus in an article written for the Daily Telegraph in early February 2024 for the response to her introduction of a new wave of trickle-down economic policy and uncosted decreased taxation for the wealthy in the middle of a cost-of-living crisis. Her policy crashed the British economy, and her denial would be amusing, except that she has a group of right-wing Tories still united behind her in her Popular Conservative Group; they feel they have not stolen enough from the majority to give to the rich.

They also love tax cuts, again on the dubious basis that these will be invested by the rich rather than stuck in their accounts (high interest rates, baby!). Or wasted on speculation in the housing markets or merely frittered in speculation on the financial markets, only adding to further instability in the economy.

When the Con-Dems came to power in 2010, cutting the size of the public sector (viewed as a threat to private sector growth, i.e. the old crowding-out theory) was a fundamental part of Cameron and Osborne’s free market fantasies; we can find comments on the bloated debt and deficit-ridden economy created by New Labour in Cameron’s speeches in 2008, 2009 and then in his maiden speech as Prime Minister in 2010. The same theme appears in George Osborne’s Emergency Budget speech in 2010:

“Our policy is to raise from the ruins of an economy built on debt a new, balanced economy where we save, invest and export. An economy where the state does not take almost half of all our national income, crowding out private endeavour. An economy not overly reliant on the success of one industry, financial services – important as they are – but where all industries grow. An economy where prosperity is shared among all sections of society and all parts of the country.”

According to the undynamic duo, the role of government was to facilitate the private sector’s growth by cutting red tape and regulations and shrinking the public sector and those parts of the private sector supported by government policy, ensuring easy investment would lead Britain to a boom in economic activity.

Despite Cameron and Osborne arguing that we were all in it together, it was the British working class that bore the brunt of austerity, especially women and disabled people. But yes, they did put a cap on banker’s bonuses to show that they were tough on bankers, too. (This was removed initially by Kwarteng and Truss’s “mini-budget”, then put back on the shelf, but overturned in October 2023 by financial regulators despite Britain being in a cost-of-living crisis.)

Under austerity, there was an attack on public sector wages, first freezing them and then allowing a 1% increase yearly until private sector pay surpassed the public sector (this only happened right before the pandemic), undermining wages and wage growth. Attacks on benefits undermined wage incomes. Zero-hours contracts (which threw especially younger working-class people into the reserve army of labour) and limited capital investment (because wages are so low it does not pay to introduce machinery) have also impacted productivity. The underfunding of our public sector undermined the NHS, social care, education, and the provision of all government services.

The latest pile of nonsense is that somehow it is the fault of workshy disabled people and women that the economy is not growing and that they must contribute to society by working from home. If listening to their nonsense makes you feel as though you are reading the 1834 Poor Law Reform, it is because they are saying the same nonsense used to force the “undeserving poor” into workhouses for being dissolute and work-shy.

Rather than criticising working-class people for insufficient productivity, they can take responsibility for driving wages so low that it makes no sense to introduce technical changes in the production of goods and services in the private sector and by refusing to invest in the public sector.

Rather than take responsibility for their appalling “race to the bottom”, they have blamed economic stagnation (and now recession) on the lazy British working class, on disabled people and women who have dropped out of the labour market due to limited access to free child care and having to provide support and assistance for family members with impairments due to the appalling level of social care (all the fault of successive Tory governments).

Rather than provide childcare and a coherent system of social support and assistance, they want to force women into work and will hold them responsible when this ends disastrously for children and disabled people. They also do not realise that if they want disabled people to work, they will need businesses to make reasonable adjustments (and why will they since wages are so low that it interferes with profit maximisation criteria), as well as recognise that disabled people need personal assistants and computers (even if they are forced to work from home).

It is also debatable whether they can force people to work given that they have not gotten rid of that pesky European Human Rights law (which was incorporated in British Law) around forced labour, which only allows forced prison labour (again a present to the US whose economy relies on forced prison labour).

Art (53) Book Review (121) Books (114) Capitalism (65) China (80) Climate Emergency (98) Conservative Government (90) Conservative Party (45) COVID-19 (44) Economics (40) EcoSocialism (55) Elections (83) Europe (46) Fascism (56) Film (49) Film Review (68) France (70) Gaza (60) Imperialism (98) Israel (124) Italy (46) Keir Starmer (52) Labour Party (111) Long Read (42) Marxism (48) Palestine (169) pandemic (78) Protest (152) Russia (340) Solidarity (142) Statement (48) Trade Unionism (141) Ukraine (346) United States of America (132) War (368)