Source > Asylum Magazine

When Judy Singer theorised the concept of neurodiversity, in her seminal 1998 thesis, she drew on two key traditions. One was a Marxism that emphasised how the concept of the ‘normal’ body was determined by material conditions and the capitalist mode of production. This is the tradition of the social model of disability, which emphasised that alleviating disablement required radically changing society, not just individual psychological or medical solutions.

The other was the liberal political tradition, which emphasised civil rights, recognition, and acceptance of difference. This was less about radical systemic change or anti-capitalism and more an approach that we might call the mainstream politics of recognition. According to this view, we need to change attitudes towards neurodivergent people, overcome deficit-based narratives, and enshrine new rights so that neurodivergent people can thrive.

Since Singer’s call to arms, most neurodiversity advocacy has been more in this latter, liberal tradition. While social models are often drawn on, they are typically used to focus on the changes needed to accommodate individual disabilities rather than to push for systemic change. And the vast majority of neurodiversity discourse still focuses on acceptance, rights, and recognition, pushing for society to change attitudes and to increase inclusivity.

Production

I contend that, for neurodiversity emancipation to be achieved, we need to go back to the Marxist roots of neurodiversity theory. To be clear, it is not that I don’t think recognition and rights are important. Rather, it is that these will never be fully achieved without significant changes in our material conditions. It is also unlikely they will change all that much under capitalism.

From a Marxist perspective the problem is about material conditions. Under capitalism and its colonial roots, bodies and minds are valued most fundamentally in terms of their perceived ability to contribute to productivity. Each of us is seen as an individual that can either contribute to, or drain, the economy. Moreover, depending on the prevailing means of production, the bodily and cognitive norms will shift, meaning those outside these norms will be discriminated against. For instance, given the rapid switch from manufacturing to services economies, the ideal worker went from being physically strong and good at repetitive tasks to hyper social and flexible.

Part of the issue here is that capitalists constantly need to revolutionise the means of production to stay ahead of their competitors. The needs of capital will soon change again, making new norms with new boundaries. But at each point there is an inside and an outside group, with the latter being discriminated against. The out group will be forced outside of work or into criminalised conditions and incarcerated in huge numbers. This will always happen under capitalism and legal rights will likely only offer a partial defence against this, especially for multiply marginalised people.

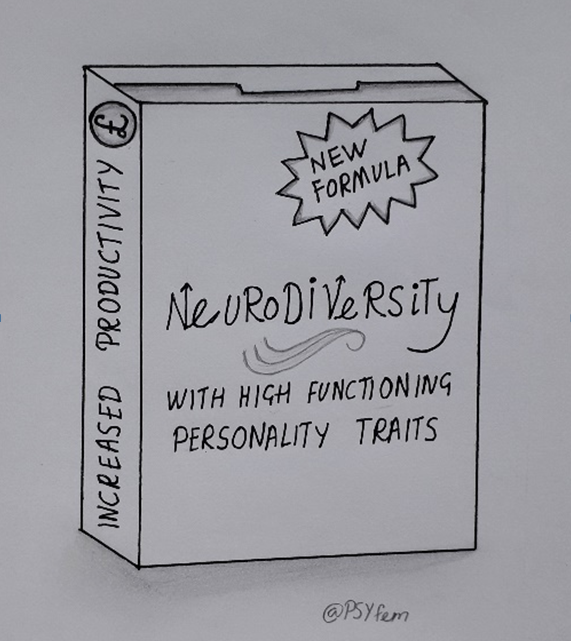

This means that an emphasis on changing attitudes or getting neurodivergent people with specific diagnoses into work by focusing on their ‘strengths’, will not change the deep structures that reproduce neurodivergent oppression. It will only mean that a select few neurodivergent people – usually those who are wealthy, white, and so forth – will be valued, at the expense of the majority of neurodivergent people. This will especially exclude those neurodivergent people who can’t work in any currently recognised sense, and who will likely always need high levels of state support under any mode of production.

Alienation

Another key issue is alienation. This is Marx’s term for how capitalism alienates us both from parts of ourselves and from each other by forcing us to constantly sell parts of our selves just to survive. By understanding neurodivergent suffering within this framework we can get to the root of the issue. What is often called ‘autistic masking’ (when neurodivergent people learn, practise, and display certain behaviours and suppress others in order to conform to neurotypical expectations) for instance, could be seen not as an autism specific issue. Rather, it could be seen as one form of alienation that stems from the requirement to sell one’s self in modern services economies. While this is alienating for everyone, it seems to be particularly hard for those who are further away from the neurotypical ideal.

It is important to stress that neurotypicals are also harmed by alienation. Although they usually have closer proximity to the ideal ‘norm’, this just means they can work longer hours and be over-used and alienated. This surely contributes to the high levels of anxiety and depression even neurotypicals experience today. Capitalism thus constructs and valorises the neurotypical while mercilessly exploiting them. Looked at this way, we can move our analysis away from single issue politics and towards analysing how dominant systems are bad for everyone. From a Marxist perspective, the neuronormativity of capitalism is bad for both neurodivergents and neurotypicals.

What then should neurodivergent Marxists work towards? First, we must collectively develop a materialist analysis of neurodivergent disablement and neurotypical alienation. This would frame neurodivergent discrimination as stemming from the current material conditions of society. It would also politicise mental illness through an analysis of alienation. In turn, our praxis must focus efforts on anti-capitalist organising, direct action, and world-making. It will be vital to build more bridges with other oppressed groups to work towards collective liberation for everyone regardless of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, or ability.

Emancipation

To be clear, to forward a Marxist analysis of neurodiversity does not necessarily mean committing to any single specific form of socialism. Clearly, some forms, such as Stalinism were just as bad for neurodivergent people as capitalism has been. We need to understand exactly what went wrong in these cases too, so we do not repeat the same errors. Still, neurodivergent Marxism does require developing some alternative or another. Working out what this might be – and organising towards it – is what neurodivergent advocacy needs to turn to if it is to achieve neurodivergent emancipation.

Now is the time to take that huge amount of neurodivergent energy and power that has been gathering – and channel it towards deep systemic change.

Robert Chapman (they/them) is a neurodivergent philosopher. Blog: https://criticalneurodiversity.com/ Twitter: @DrRJChapman

The Anti*Capitalist Resistance Editorial Board may not always agree with all of the content we repost but feel it is important to give left voices a platform and develop a space for comradely debate and disagreement.

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Event Video Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Global Police State History Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party London Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants NATO Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War