This historic show was over five years in the making. Dedicated teams of researchers appealed to those feminists who lived through this period or to those managing existing local collections to send in any materials they felt were relevant to the show.

There is an archival side to the show, where photos, news reports, documents, leaflets, posters, films, and books reflect the activity and richness of the movement. On the other hand, there are the specific artistic products of the time: paintings, photos, video, and installations, usually by individual artists but sometimes the product of collective work. There is an overlap between the two elements; artistic creativity inspires some of the political posters calling for actions or meetings. Conversely, the individual artists wanted to place their individual works at the service of the movement rather than for personal enrichment.

In the catalogue, the three advisors to the project, Althea Greenan, Griselda Pollock, and Marlene Smith, summarise some of the key issues that the exhibition addresses:

These artists broke the boundaries of art in their many media, practices and locations, while fostering audiences that were themselves diverse. Their embrace of new materials, technologies and sites of art contributed to the radical expansion and complexity of what would be first termed ‘post-modern’ and later ‘contemporary art’ – notably in areas such as performance, film and video, installation and audience-engagement, as well as across drawing, painting, sculpture and photography (…)

Feminism has often been understood too narrowly as only a political movement. However it was – and still is – also a cultural movement reshaping art, literature and film – all of which have been challenged by feminism not only to end all discrimination against all women, but to acknowledge the gross injustices around race, class and sexuality.(…)

…these artists were making art for people other than the collectors, responding neither to the market nor to a curated supply chain of what is selectively considered ‘contemporary’. They created with a sense of community that was urgent. It was about speaking to different communities, and also becoming a community of artists.

This exhibition joyfully, and critically challenges a dereliction of duty by the museums, curators and critics, for not sharing with the British public what happened in British art in these decades. Museums and curators did not research, conserve or exhibit many amazing works by British artists.

pp 10/11 in Tate Catalogue

As Linsey Young, the lead curator, points out in an overview of the exhibition, she wants to recognise the diversity of the movement—its very messiness, as she says. Certainly, this makes this show quite distinct from the one-person retrospectives that you visit.

It is also incomplete. Some artists could not be located, some have passed on before their time, and some artworks have been lost because many woman artists did not have the resources to store their work or simply lost hope that someone might be interested in exhibiting it.

A number of my friends, after visiting the exhibition, have mentioned two things. First, it is sobering to think that our political lives and experiences are now part of semi-official history. We can see the hand-stapled leaflets and pamphlets made with Gestetner printers. Those wax stencils had to be typed right; unlike today’s computers, it was much more difficult to get a perfect copy. I saw a number of publications that we used to sell on our bookstalls. Second, the sheer scale and density of the material and art that came out of the movement still come as a surprise. The fact that you can see a number of things for the first time reinforces the sense that this was a truly historic political movement that made real changes for women in the course of our own lifetime.

Women in Revolt follows more or less a chronological approach, starting with the first National Women’s Liberation Conference held in Oxford in 1970. This launched the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) in the UK. Another seven conferences were held up to 1978, and the WLM demands were hammered out:

- Equal pay now

- Equal education and job opportunities

- Free contraception and abortion on demand

- Free 24-hour nurseries

- Financial and legal independence

- An end to all discrimination against Lesbians and a woman’s right to define her own sexuality

- Freedom from intimidation or use of violence or sexual coercion, regardless of marital status, and an end to all laws, assumptions, and institutions that perpetuate male dominance and men’s aggression towards women.

The strength of the subsequent movement has meant real gains have been made on these demands, reflected in a number of progressive acts of parliament such as the Equal Pay Act and the existence of domestic violence refuges, for instance. However, the WLM demands are far from being fully met. Girls are achieving better than boys in exams, but the top jobs are still held by men. Abortion is not particularly restricted but is not on demand. Contraception is not free, and 24-hour nurseries for mothers, whether at work or not, do not exist. Generally, you have to work a certain number of hours part-time to qualify for free nursery care today. As the mass mobilisations over the Sara Everard case show, sexual violence and femicide by men are still endemic.

Everyone will have their own favourites from the show. I will comment on a selection.

This painting is displayed at the start of the exhibition. I have never seen it before, and it made an impression on friends who saw it too. Such a presentation of the difficulties of motherhood was not common at that time. The facial expression is brilliantly captured, and you can almost feel the baby keening away from the mother’s arms and hear its screaming. The discordant lines and disarray in the background add to our sense of dislocation and pain the woman is experiencing. Various objects like the clothes drying stand, the stove, and the table crowd in on the figures, suggesting the daily claustrophobic grind of household tasks. The colours are subdued and drab, apart from the deep red of the baby’s romper suit. The lines on the baby’s top seem to amplify the screaming and tension. Scott was a Marxist-Leninist activist with a socialist realist style, although this painting is much more subtle than much in that tradition.

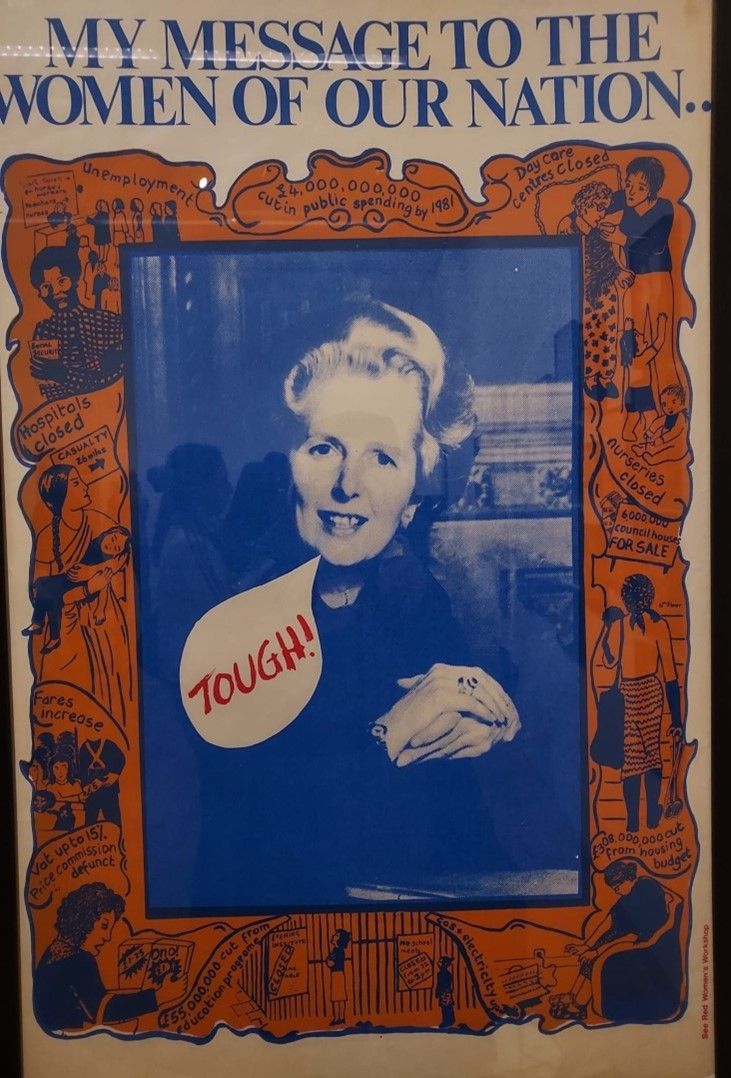

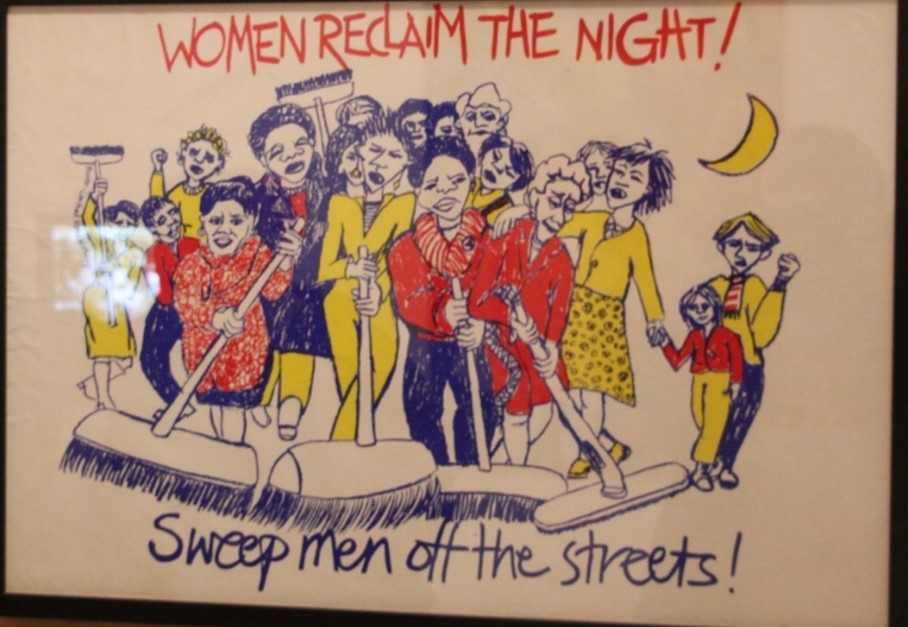

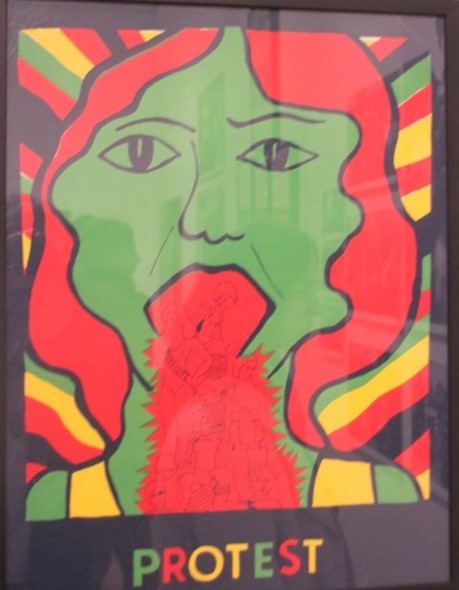

Alongside the more conventional paintings by individual artists like Scott, the show displays many collectively produced posters, photos, or movable displays that were widely distributed and can be considered as agitprop to build the movement. Such creative works also have original and artistic qualities but were designed for plastering on walls or to be pinned up in workplaces, community centres, schools, or universities. They now proudly stand alongside the oil paintings and installations by individual artists that were displayed in galleries or exhibitions. Women in Revolt, in this way, questions a rigid hierarchy of artistic worth and the sanctity of the individual artist.

The Red Women’s Workshop made posters that were accessible and affordable. All work was authored collectively, with no hierarchy and no one individual taking credit. All tasks and skills were shared. Forty-five women worked in it during this time. This two-colour poster combines a photomontage technique with a border that, from a distance, is reminiscent of Morris’s decorative arts and crafts style. It is actually composed of cartoon figures featuring different women’s campaigns. Tough, my message to the Women of our nation 1979 looks like a simple political poster, but there is a lot of design and art going into it.

Lenthall Road was another collaborative collective that was active until the 1990s. Here, the poster features the forerunner of a campaign that continues to this day in light of the Sara Everard case. The red, yellow, black, and white screen print has an immediate impact with a simple, clear message as effective as many of the advertisements that people are paid astronomical sums to create. The foregrounding of the outsized brushes visually reinforces the main idea of decisive action to reclaim the streets.

I remember watching people produce these sorts of screen prints, and it is a long and tricky process, particularly when it is created with several colours. We are lucky today that small campaigns and organisations can produce high-quality posters in a fraction of the time. Of course, today’s posters are not necessarily any better from an artistic or design point of view. Reclaim the night/streets stuck as the main name of the campaign for many years, again right up to the present day.

Another poster from the Red Women’s workshop shows how the artists borrowed from the Pop Art school, which was also extensively used on the covers of vinyl records at the time. Images of women marching and protesting emerge from the woman’s mouth; the slogans we shout are the red blood of the movement.

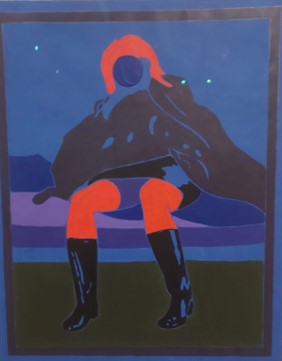

Today, the movement to defend trans rights is a target in the Tory Culture War offensive that is partially echoed by Starmer’s Labour. Some of the debate today around gender in the movement and on the left is pretty toxic. The exhibition displays several striking pictures by a trans woman artist, Erica Rutherford. During the period that the show covers, trans rights and liberation were not as much a front-line issue as they are now.

Greenham Common was the name of the area around a US airbase where thousands of women regularly demonstrated during the campaign against US President Reagan’s plan to station nuclear cruise missiles in Britain. Many hundreds kept a permanent protest camp going outside the base. Women often attached objects they valued to the perimeter fence. The exhibition gives quite a lot of space to the campaign; there is a virtual campfire you can go and sit around, and there is this installation, recreating the fence that spans nearly the entire room.

Written in large letters above the installation are the words of the novelist, Virgina Woolf:

Not by repeating your words and following your methods but by by finding new words and creating new methods. We can best help you to prevent war.

Virginia Woolf (1938)

One of the strengths of the show is the space given to black and Asian women, their campaigns, and their art work. Their oppression as women is combined with the impact of racism and the position of many in the most exploited, low-paid sections of the working class. There are photos and information on the long strike of mostly Asian women workers at Grunwicks. Several great individual black and Asian artists also have pictures displayed.

Sanderson is of Malaysian/British heritage, and she challenges stereotypes of women whose ethnic origins led to their ‘exoticisation’ by a society marked by racism and its colonial past. Here the artist is nude and the subject is discreetly dressed—the artist is reversing the ‘normal’ relationship established by the male-dominated art world. There is a strong, quiet dignity about this picture, expressed through the subtle colours.

The Financial Times review thought this was one of the best pieces in the show:

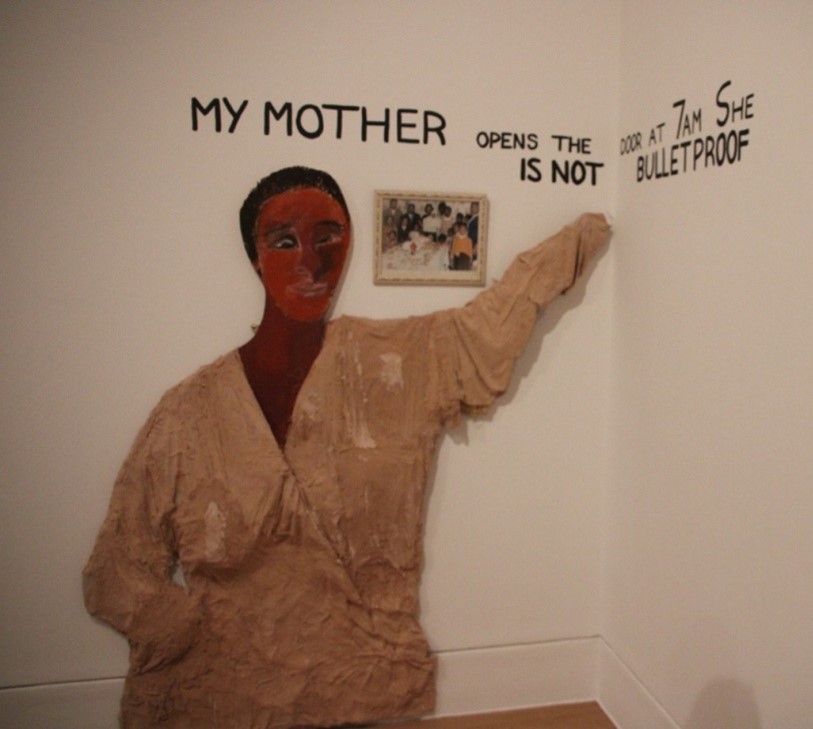

Marlene Smith’s “Good Housekeeping III” is a larger than life multimedia relief/sculpture of a black figure with a mask-like Picasso face, clothed in white, holding fast to the wall alongside a happy family snapshot. Above, the caption reads “My mother opens the door at 7am. She is not bullet proof”. She is Cherry Groce, mistakenly shot and paralysed by police officers in an incident sparking the 1985 Brixton riots.

The exhibition includes a range of female artists from the Black and Asian communities. Biswas explores women’s situation in the context of history and colonialism. In this picture, she references the Indian god Kali rooting out evil.

Lubaina Himid is key to raising the profile of Black artists. She won the Turner Prize in 2017 and had a retrospective at the Tate Modern in 2022 (see our review here). She was important in the formation of the Black Arts movement of the 1980s, which helped secure more visibility for Black artists. Here we see her directly criticising the way Black people and Black artists are subjected to a ‘carrot and stick’ approach. Repressed, hidden, but, on the establishment’s terms, sometimes paraded to project a liberal, multicultural modernism. The work is constructed of painted cardboard images.

Talking with friends and comrades who have also seen the show, most were very positive, with many saying they want to go again since there is so much to take in. Inevitably, there are a few ways people think the show could have been even better.

Women in Revolt has an awful lot of material from London (and Hackney is particularly represented!) and maybe more effort could have been made to reflect a more national spread. However, I suppose the curators took the resources where they were, and undoubtedly, the movement was probably deeper and more extensive in the London region than anywhere else. Radicalised women were more likely to want to leave provincial towns for the relatively greater freedom in London.

Someone else thought the music and theatrical production of the new feminism were underrepresented, apart from an original section on the role of punk music and gender. Certainly, I remember there were a number of radical women’s theatre groups, such as the Monstrous Regiment, Spare Tyre, and the Women’s Street Collective.

And although the show is about feminist movements in Britain, it might have been relevant to have at least one display on the international links with the US or European countries.

Nevertheless, this is an essential exhibition that records the huge contribution the women’s movement has made to improving conditions for women and how art played an important role within it in raising consciousness and mobilising action.

This review can only ever be a partial one given how large the show is, and we would be very happy for our readers to send in short or longer pieces setting out their responses and maybe choosing different highlights.

Note: Photos of art works are by Dave Kellaway and Pete Firmin.

Art Book Review Books Capitalism China Climate Emergency Conservative Government Conservative Party COVID-19 Creeping Fascism Economics EcoSocialism Elections Europe Event Video Far-Right Fascism Film Film Review France Gaza Global Police State History Imperialism Israel Italy Keir Starmer Labour Party London Long Read Marxism Marxist Theory Migrants NATO Palestine pandemic Protest Russia Solidarity Statement Trade Unionism Trans*Mission Ukraine United States of America War

I went to the exhibition and took many photographs. Unfortunately they are amateurish and a bit wonky hence not really up to publishing standard though I may put some up on my facebook page.

The exhibition is enormous and I will probably make a second visit. As you say its a pity there were no women’s theatre groups exhibited given there is plenty of material at ‘Unfinished Histories’ an archive that documents women’s, socialist and LGBT+ material from the same period as this exhibition. I would have like to have seen photos of ‘Hormone Imbalance’, a radical lesbian theatre group from the 1970s. The name threw back in the face of the establishment one of the stupid oppressive theories about the ’causes’ of lesbianism. An amazing era saturated in radical, revolutionary politics and above all much of the art produced was collaborative as well as the work of talented individuals which reflected the political temper of the time towards a more collectivist view of art production that militantly proclaimed an unashamed agit prop stance to change the world for the better.